How do house prices feed into inflation rates around the world? It’s important for central banks, and for bond investors.

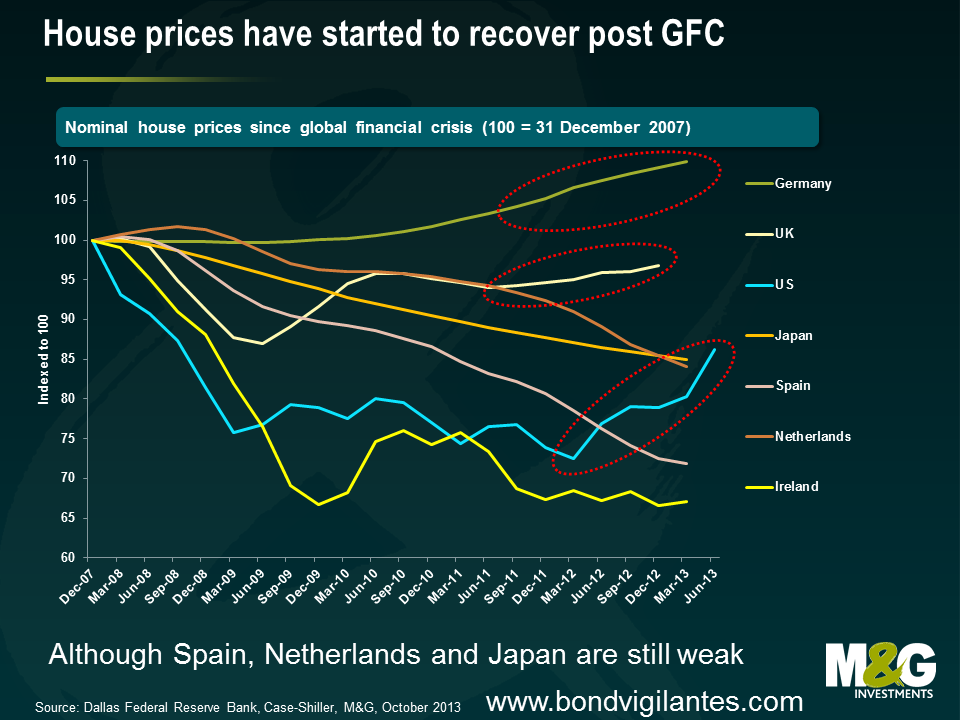

After the collapse in real estate prices in many of the major developed nations during and after the Great Financial Crisis, housing is back in demand again. Strong house price appreciation is being seen in most areas of the US, in the UK (especially in London), and German property prices have started to move up. We’re even seeing prices rise in parts of Ireland, the poster child for the property boom and bust cycle. I wanted to take a quick look at what rising house prices do for inflation rates. Not the second round effects of higher house prices feeding into wage demands, or the increased cost of plumbers and carpets, but the direct way that either house prices, mortgage costs and rents end up in our published inflation stats. Also, the question about whether central banks should target asset prices is another debate too (there’s some good discussion on that here).

There is no simple answer to the question “how do house prices feed into the inflation statistics”. It varies not just from country to country, but also within the different measures of inflation within one geographical area. But given central banks’ rate setting/QE behaviour is determined by the published inflation measures it’s important to understand how house prices might, or might not, drive changes in those measures.

The US

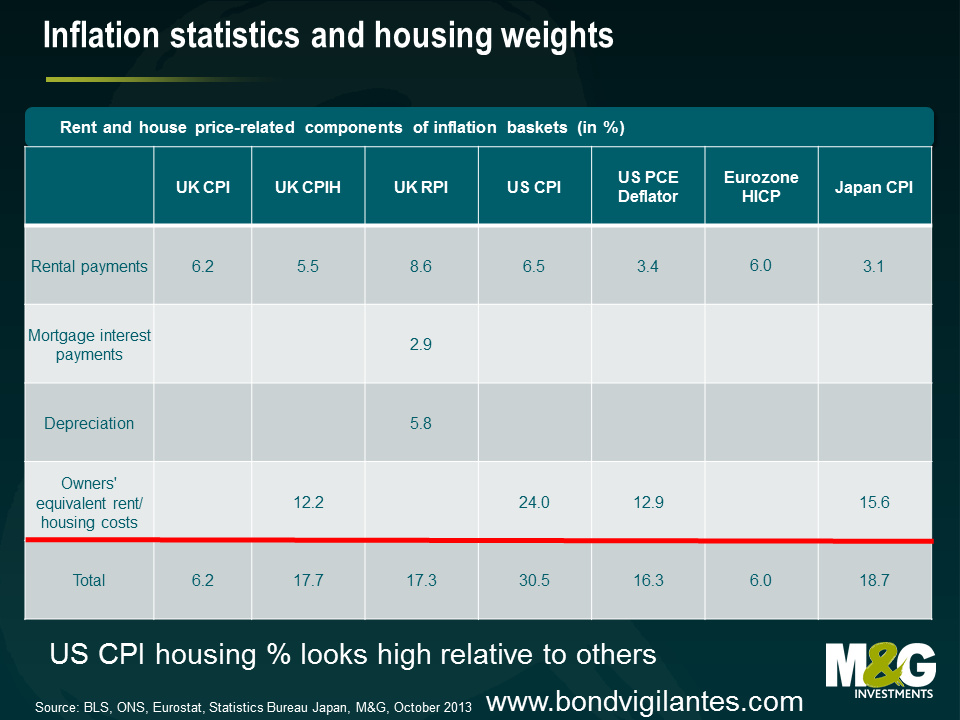

“Shelter” is around 31% of the CPI which is used to determine the pricing of US inflation linked bonds (TIPS), but just 16% of the Core PCE Deflator, the measure that the Federal Reserve targets. The PCE is a broader measure, with much bigger weights to financial services and healthcare, so shelter measures therefore have to have a smaller weight in that measure. The CPI shelter weight looks high by international standards. For the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the purchase price of a house is not important except in how it influences the ongoing cost of providing shelter to its inhabitants. The method that the BLS uses to determine what those costs might be is “rental equivalence”. It surveys actual market rents, and augments this data by asking a sample of homeowners to estimate what it would cost them to rent the property that they live in (excluding utility bills and furniture). You can read a detailed explanation of this process here. In both the CPI and PCE, pure market rents are given around a quarter of the weight given to OER, Owners’ Equivalent Rent. There are problems with this – and not just with the accuracy of the homeowners’ rental guesses. Having rents and rental equivalence in the inflation data rather than a house price measure means that you can have – simultaneously – a house price bubble, and a falling impact from house prices in the inflation data. We’ve seen times when a speculative frenzy means house prices rise, but the impact of that speculation is overbuilding of property (just before the 2008 crash there was 12 months of excess inventory of houses in the US compared to a pre-bubble level of around 5 months) leading to falling rents. The reverse happened as the US recovered. House prices continued to tank, but because of a lack of mortgage finance more people were forced to rent, pushing up rents within the inflation data.

The UK

How house prices feed into the UK inflation data depends on whether you care about CPI inflation (which the Bank of England targets) or RPI inflation (which we bond investors care about as it’s the statistic referenced by the UK index linked bond markets). House prices directly feed into the RPI, but because house prices have little direct input into the CPI, the recent trend higher in UK property will lead to a growing wedge between the two measures – good news for index linked bond investors! The RPI captures house price rises in two ways – through Mortgage Interest Payments (MIPs) and House Depreciation. Mortgage payments will increase as the price of property rises, but they will most quickly reflect changes in interest rates. For example Alan Clarke of Scotia estimates that a hike in Bank Rate of 150 bps would feed almost immediately into the RPI, adding 1% to the annual rate. This is despite the trend in the UK for people to fix their mortgage payments. Housing Depreciation linked to UK house prices with a lag, and is an attempt to measure the cost of ownership (a bit like the BLS’s aim with rental equivalence) but has been criticized as overstating the cost of ownership in rising markets as house price inflation is almost always about land values accelerating rather than the bricks and mortar themselves. Land does not depreciate like other fixed assets (no wear and tear). Housing is very significant in the UK RPI, making up 17.3% of the basket (8.6% actual rents, 2.9% MIPs, 5.8% depreciation).

The UK’s CPI is a European harmonised measure of inflation. It only takes account of housing costs through a 6% weight on actual rents. There has never been agreement within the EU about how wider housing costs should be measured! Countries with high levels of home ownership have different views from countries with a high proportion of renters. Housing is around 18% of the expenditure of a typical person in the UK, so the Office of National Statistics regards the current CPI weight as a “weakness”. They therefore are now publishing CPIH, which includes housing on a rental equivalence basis (the same idea that the ONS measures “the price owner occupiers would need to rent their own home” as a dwelling is a “capital good, and therefore not consumed, but instead provides a flow of services that are consumed each period”). CPIH has a 17.7% weight to housing, but remains an experimental series, and plays no part in the official monetary targets.

The Eurozone

The European Central Bank targets CPI inflation, at or a little below 2%. As mentioned above the harmonised measure that Eurostat produces does not include any measure of housing other than actual rents, with a weight of 6%. If you think house price inflation (or deflation) is important for policymakers this low weighting has probably never mattered since the Eurozone came into existence. Although there have been pockets of very high house price inflation (Spain, Ireland, Netherlands) because the Big 3, Germany, France and Italy have had very little house price movement I doubt that a CPIH measure would be terribly different. We are, however, now seeing some upwards movements in the German residential property market in “prime” regions – albeit it as Spanish and Dutch house prices continue to freefall. It’s also important to note the range of importance of rents within the individual countries’ CPI numbers. For Slovenians it makes up 0.7% of their inflation basket, but for the Germans it is 10.2%.

Japan

Housing makes up 21% of the headline CPI. Like the US CPI the Japanese statistical authorities use a measure of an “imputed rent of an owner-occupied house” as well as actual rental costs. Again the imputed rents from owner occupiers (15.6%) dwarf the actual numbers from renters (5.4%) – aren’t these large weightings to imputed rents here and elsewhere a bit worrying? How would you homeowners reading this go about guessing a rent for your property? I’d only get close by looking at websites for similar places to mine up for rent nearby. Is that cheating?

So why does this matter? Well if there is no correlation between house price inflation and consumer price inflation then it probably doesn’t. But intuitively both the direct impact on wage demands of workers who see house prices going up, and the wealth effect on the consumption of those who see their biggest asset surging in value should be significant. Therefore central banks will be missing this if they use statistics where the relationship between house prices and their impact in those statistics is weak.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

18 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox