Government bonds – when a safe haven may not be not a safe haven

We first talked about cracks appearing in Euroland in June, and expanded this to include emerging market government bonds in October. Over the past few months, the trend of rising sovereign default risk has accelerated, and particularly in Europe where we’ve seen downgrades to the sovereign debt of Greece, Portugal and Spain. It’s probably a matter of time until the UK follows. In today’s environment, what can you define as ‘risk free’?

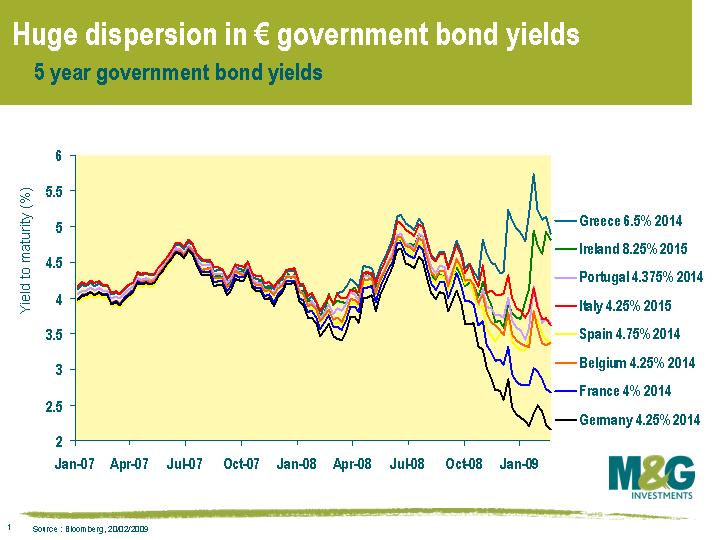

The attached chart shows the yields on a selection of euro denominated government bonds. At the beginning of 2007, a Greek government bond maturing in 2014 yielded only 0.15% more than a German government bond with a similar maturity. Now, the German bond yields a shade over 2%, while the Greek bond yields almost 5%. Bearing in mind that even German government bonds have an element of credit risk, perhaps as much two thirds of the Greek government bond yield is compensating you for the risk of default.

It’s slightly harder working out how much credit risk there is on a 5 year gilt, because it’s obviously not issued in euros. But if you look at the credit derivative market, the 5 year CDS on UK government bonds is about 165 basis point (so, if you wanted to insure £100,000 of gilts for 5 years, you’d earn £1,650 per year). According to the credit derivative market, there is a slightly higher risk of the UK government defaulting than for Belgium (rated AA+), Spain (rated AA+) and Portugal (rated AA-), though not quite as high as the default risk of Italy (rated AA-). Cash bond yields often don’t quite tally with the default risk implied by derivative markets, although yesterday Portugal issued a government bond where the two did match up. If you assume that the credit risk implied by the CDS market is correct for UK gilts, then of the 2.6% yield you can get on a five year gilt today, more than half of this yield is now credit risk.

Could we get to a situation where corporate bond yields are lower than government bond yields for the better quality corporate issuers ? This is already happening in the case of Greek government bonds – investors now need to analyse Greek government bonds and ask whether they should lend money to the Greek government for 5 years, or for a very similar yield and a maturity, should they buy euro denominated bond issues from Vodafone, Carrefour, BHP Billiton, Deutsche Telekom or Diageo? If the UK economy deteriorates much further then there is no reason that the same thing can’t happen in the UK. It could even happen in the US, Germany or France, particularly if you consider the ugly technical picture that could result from the huge amount of government bond issuance that will be necessary over the coming years.

Bond investors and citizens typically consider their respective governments to be their safe haven. However, within the Eurozone investors are confronted with a choice of safe harbours beyond their national borders. Therefore risk averse capital will tend to flow into the perceived safest harbours at the expense of others. This understandable reaction in difficult times begins to become self fulfilling as a flow of cash from one to the other makes it relatively safer.

Recent months, not entirely unexpectedly, have seen increasing speculation that the Euro may see one or more member states depart for a variety of reasons. This in itself deserves a separate blog and I’ll do my best to pen something in the near future. For now, lets just say that although it isn’t our core scenario, such an outcome shouldn’t be discounted.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

18 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox