It’s hard to get anyone to make a bear case for EM, so I’m going to try

The EM story is a strong one – in sharp contrast to the developed world, EM counties tend to have favourable sovereign/consumer debt dynamics, current account surpluses, high savings rates (implying scope for a pick up in consumer demand) and strong demographics. Continued globalisation and liberalisation should be to the advantage of these counties. Reflecting these opportunities, US mutual fund flows into EM debt have seen the sharpest increase of any asset class year to date versus this time last year, and I suspect it’s a similar story for EM equity. However you rarely hear about the risks in EM, only the opportunities, so I thought I’d try to present the other side of the argument.

The first thing I’d like to highlight is the risk posed by the sheer size of the flows themselves. Like the rest of the desk here, I’m a confirmed Reinhart and Rogoffian, and it’s easiest to just quote the authors;

“Countries experiencing sudden large capital inflows are at a high risk of having a debt crisis. The preliminary evidence here suggests the same to be true over a much broader sweep of history, with surges in capital inflows often preceding external debt crises at the country, regional, and global level since 1800 if not before.”…

“Emerging market borrowing tends to be extremely pro-cyclical. Favorable trends in countries’ terms of trade (meaning typically, high prices for primary commodities) typically lead to a ramp-up of borrowing that collapses into defaults when prices drop.”…

“The problem is that crisis-prone countries, particularly serial defaulters, tend to over-borrow in good times, leaving them vulnerable during the inevitable downturns. The pervasive view that “this time is different” is precisely why it usually isn’t different, and catastrophe eventually strikes again.”…

“There is a view today that both countries and creditors have learned from their mistakes. Thanks to better-informed macroeconomic policies and more discriminating lending practices, it is argued, the world is not likely to again see a major wave of defaults. Indeed, an often-cited reason these days why “this time it’s different” for the emerging markets is that governments there are relying more on domestic debt financing. Such celebration may be premature. Capital flow/default cycles have been around since at least 1800—if not before. Technology has changed, the height of humans has changed, and fashions have changed. Yet the ability of governments and investors to delude themselves, giving rise to periodic bouts of euphoria that usually end in tears, seems to have remained a constant.”

So, large capital inflows result in tighter credit spreads on external debt and lower yields on domestic debt, which eventually incentivise EM governments or corporates to issue more debt, and once the hot money goes into reverse the EM countries suddenly find themselves facing liquidity and/or solvency problems. There are a few early warning signs of this occurring, for example in just the past week, three Indian banks have taken advantage of strong EM investor demand for anything with a pulse and a yield to issue USD paper, while at the sovereign level, countries such as Korea do indeed appear to be taking advantage of cheaper financing conditions to increase local currency issuance. Others, particularly in Eastern Europe, are relying on capital inflows to finance budget deficits.

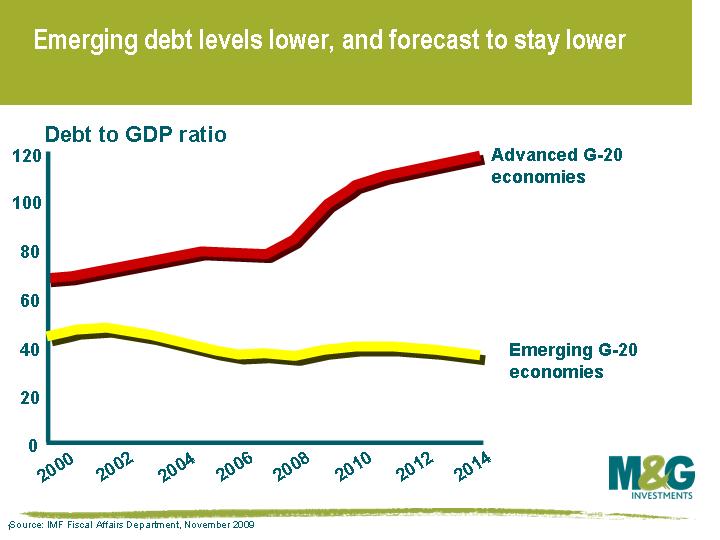

But EM debt levels are currently very low so there’s nothing to worry about, right? Well EM sovereign debt levels are lower than developed country debt levels, and the IMF estimate that this difference is likely to increase over time (see chart), but this is assuming that this time it really is different and EM countries don’t go on a debt binge. Also, it’s important to note that a comparison of developed and EM countries is potentially misleading. EM countries have a much lower tolerance for debt than developed countries for a number of reasons, including investors having greater confidence in the strength and independence of institutions, developed countries having greater credibility with investors (owing to a history of honouring their debts), developed debt markets offering superior depth and liquidity (allowing debt to be more easily rolled over), developed markets demonstrating a history of greater macroeconomic stability and tax revenues in developed countries typically being much higher as a percentage of GDP. All these things mean that bond yields (and hence interest payments) tend to be lower in developed countries, allowing higher sustainable debt levels as a percentage of GDP.

But EM debt levels are currently very low so there’s nothing to worry about, right? Well EM sovereign debt levels are lower than developed country debt levels, and the IMF estimate that this difference is likely to increase over time (see chart), but this is assuming that this time it really is different and EM countries don’t go on a debt binge. Also, it’s important to note that a comparison of developed and EM countries is potentially misleading. EM countries have a much lower tolerance for debt than developed countries for a number of reasons, including investors having greater confidence in the strength and independence of institutions, developed countries having greater credibility with investors (owing to a history of honouring their debts), developed debt markets offering superior depth and liquidity (allowing debt to be more easily rolled over), developed markets demonstrating a history of greater macroeconomic stability and tax revenues in developed countries typically being much higher as a percentage of GDP. All these things mean that bond yields (and hence interest payments) tend to be lower in developed countries, allowing higher sustainable debt levels as a percentage of GDP.

Maybe EM debt levels aren’t so low after all. In the recent paper ‘Growth in a Time of Debt‘, Reinhart and Rogoff find that economic growth has historically deteriorated markedly for a country with a public debt ratio above 90%, and for an EM economy with an external debt/GDP ratio of greater than 60%. Some EM countries are approaching (and a few in Eastern Europe are exceeding) these levels. Also, note that in ‘Debt Intolerance’, another paper that Reinhart and Rogoff wrote with Miguel Savastano in 2003, the authors find that 50 percent of sovereign defaults or restructurings since 1970 took place with external debt-to-GNP levels below 60 percent. Mexico defaulted in 1982 with a debt/GNP ratio of 47%, Argentina in 2001 with a ratio of just above 50%.

Inflation poses a significant risk to the EM story. Food and energy tend to be a much bigger part of the consumer basket for an emerging market than a developed market, so for example in Turkey (where CPI inflation in the year to February was 10.1%) food and energy forms about 30% of the inflation basket, while in India (where the Urban CPI rose 16.9% in the year to January) food prices are between 46 and 69% of CPI, depending upon which index you look at. If you believe in the EM story, you’re likely to believe in the commodity story too. Yet further commodity and food price rises risk destabilising many EM countries and could even risk derailing the global economic recovery in general. We could see the return of public unrest and tariffs (and with this the risk of more inflationary pressure), threatening a repeat of the experiences of many emerging markets in 2007 (see one of Richard’s old blogs here).

What about other risks? Each EM country obviously faces specific risks, so it may be worth very briefly focusing on each of the BRICs in turn.

Short term, Brazil faces uncertainty around the election and upwards inflationary pressure (with a series of rate hikes likely), but a far bigger medium and long term problem is the huge infrastructure spend necessary. A senior analyst at S&P told us that Brazil needs to spend an enormous US$500bn on all its infrastructure projects in the next five years, which includes things like the 2014 FIFA World Cup, 2016 Olympic Games as well massive oil project expenditure. S&P suggested that US$500bn is actually a conservative estimate and only gets infrastructure to ‘Brazilian standards’, as opposed to ‘Western standards’. The Brazilian government is looking at project finance initiatives to pay for this but it won’t be easy, and Brazil’s net public debt/GDP is already around 50%.

Russia is essentially an oil play – its budget is based around $59 per barrel, above this and it’s fine (in fact it’s more than fine), below this and the country and its fragile banks could easily unravel. I’ve already mentioned India briefly above, but as well as facing a potential inflation problem, India also has high deficits and high debt levels for an EM county (70% debt/GDP), making it potentially vulnerable. And finally there’s China, where the rate of credit growth looks like bubble-esque, and as we know, bubbles usually go pop rather than deflate in an orderly unwind. Then there’s the brewing trade spat with the US regarding China’s currency pegging policy, and probably most importantly of all, like any other country with limited political liberties, a negative economic shock can easily spiral into political upheaval.

Looking at emerging market debt specifically, it doesn’t look like markets are factoring in these risks, particularly in relation to hard currency debt. For example, long dated Indonesian USD denominated bonds yield 6.5%, which is only 1.7% more than US Treasuries, and arguably that’s not enough for a country that’s still rated junk. Ten year Lebanon USD denominated debt yields 6.3%, or 2.4% more than US Treasuries – is that a big enough yield premium for something rated B, which is only five notches above D for Default? I had a large investment bank tell me earlier this week that the 7.7% yield on some bonds issued by the Development Bank of Kazakhstan bonds was “the best risk adjusted thing out there”. They may well be right, but if so, it doesn’t say much about value in the rest of the market! Local currency EM debt still offers some opportunities, but many currencies have already come a long way.

In sum, I still stand by what I said in November – the rally in risky assets we’ve seen is largely liquidity driven, and due to deep concerns about the sustainability of the recovery, the authorities are only withdrawing the extraordinary stimulus measures very gradually. Until we see a speeding up of fiscal tightening and the beginning of monetary policy tightening, the risk rally will most likely continue over the short term, and this would be expected to continue to support emerging markets. But it doesn’t seem that the risks facing EM are getting sufficient coverage, and there are potentially significant medium and long term issues to be aware that don’t appear to be getting priced in.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

18 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox