A life less easy for the ECB

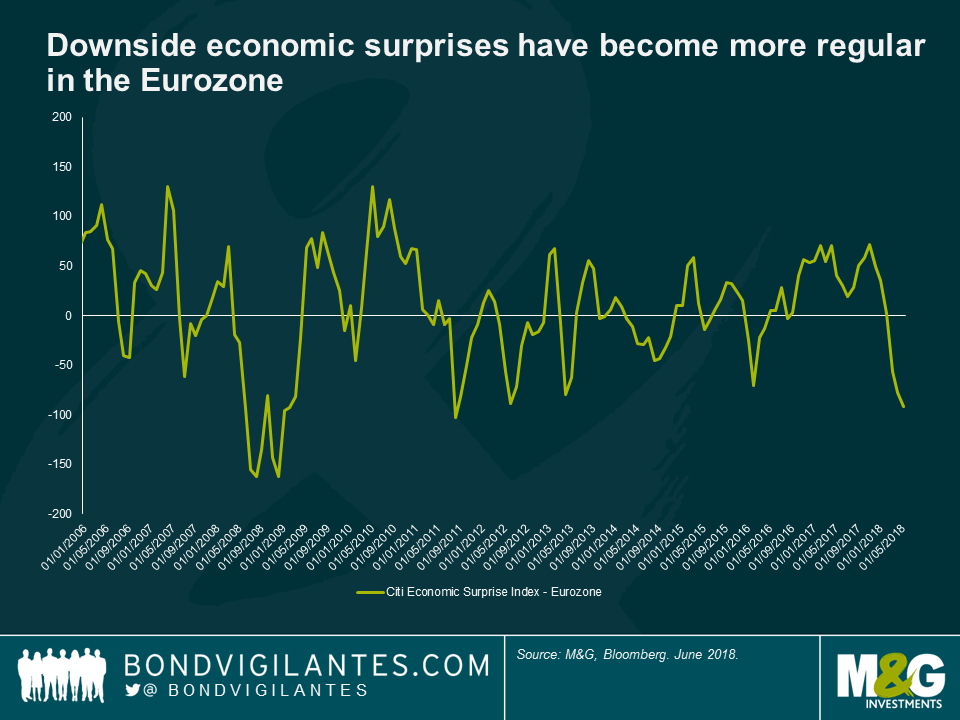

Back in 2017, the economic outlook was increasingly rosy for the Eurozone. After years of ultra-loose monetary policy, a synchronised global recovery was in train. The Eurozone economy expanded apace, regularly surprising to the upside, unemployment continued to fall, the banking system had partially recapitalised and funding costs for corporates and sovereigns alike remained low on any measure. Even the inflation picture was showing some signs of a recovery towards the ECB’s definition of price stability. Behind the scenes, the ECB must have been increasingly confident that they had turned a corner and would begin unwinding their emergency monetary policy stance.

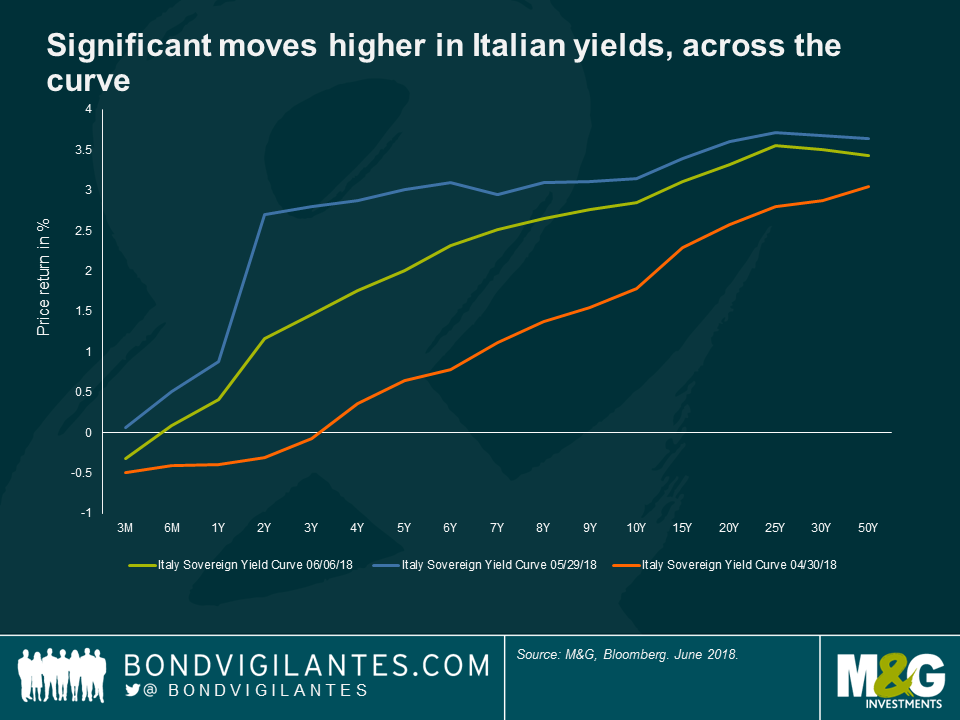

Less than a year later and their plans for normalisation have become more complicated. The economic data has weakened. And recent events in Italy have served to remind of the dangers of discounting populist politics. Whilst Italy is not leaving the Euro any time soon, the notable absence of credit risk priced into Italian assets a mere month ago was foolhardy. At the end of April 2018, ten-year Italian BTPs offered a yield below 2%, and all maturities below 3 years yielded less than 0%. A month later and BTPs yields have climbed dramatically.

The ECB will take comfort from the limited contagion to other peripheral markets thus far. Structural reforms, a stronger economy and better response mechanisms go a long way to explaining this. But dialling back stimulus in the face of increased market volatility and a tightening of financial conditions in Italy will leave the doves on the ECB Council uneasy.

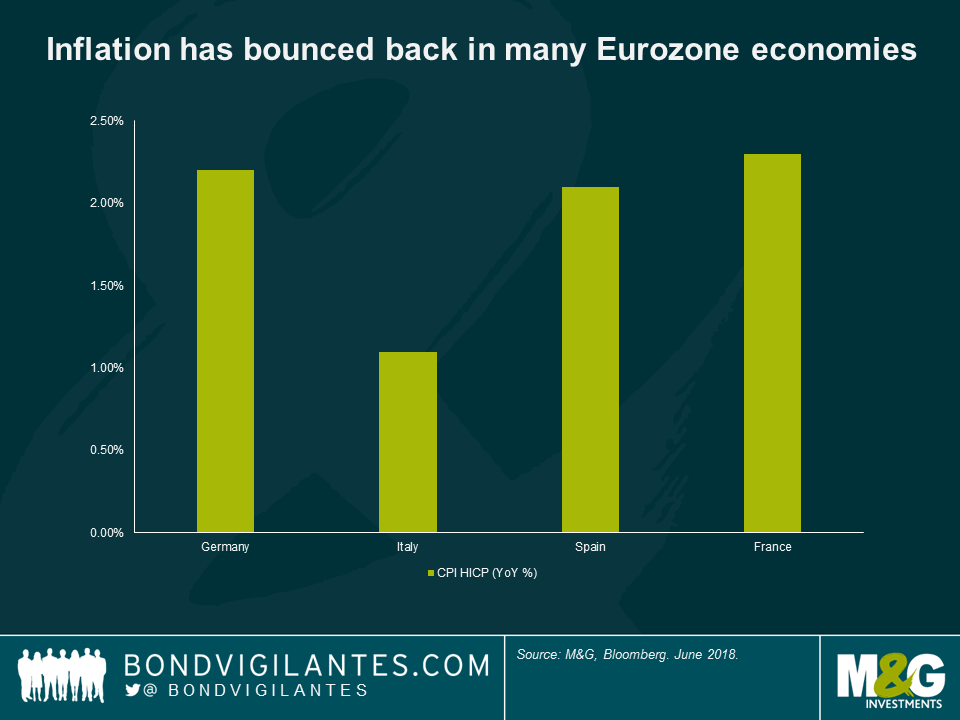

Jens Weidmann, Deutsche Bundesbank President, and other notable hawks will take a different view. They will point to recent German CPI prints of 2.2% and firming labour markets across the Eurozone. Savers continue to be forced to take either considerable term or credit risk to earn a positive real yield and there are some preliminary signs of excesses and imbalances building. Weak or practically non-existent covenant protection have become the norm in many high yield and leverage loan transactions. These concerns are not without merit.

Yet despite these risks, there is danger in tightening policy too early. Arnaud Marés at Citigroup, a former special advisor to Mario Draghi, argues that a central bank requires 300-400 basis points of rate cuts to be confident they can suitably stimulate an economy in the face of a significant economic slowdown. The chances of the ECB getting anywhere close to this watermark before the end of this current cycle are practically zero. Given the lack of fiscal firepower available to Eurozone governments, the ECB finds itself in an unenviable position. The onus remains on easy monetary policy to support economic growth in the Eurozone and the Central Bank is best served by erring on the side of caution. Put another way: they should wait until the they can see the whites of the eyes of inflation before normalising policy. Any tightening should be a gradual affair.

Mario Draghi’s term as ECB President expires in November 2019. He will want to be remembered for playing his part in pulling the Eurozone back from the abyss in 2012. He certainly will not want to be the ECB President who helped cause the very slow down his successor will face, with a largely empty box of tricks.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

18 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox