Green bonds, blue bonds, ESG bonds galore – a beginner’s guide for fixed income investors

An abridged version of this article first appeared in Investment Week (print edition, 1 February 2021, p. 14)

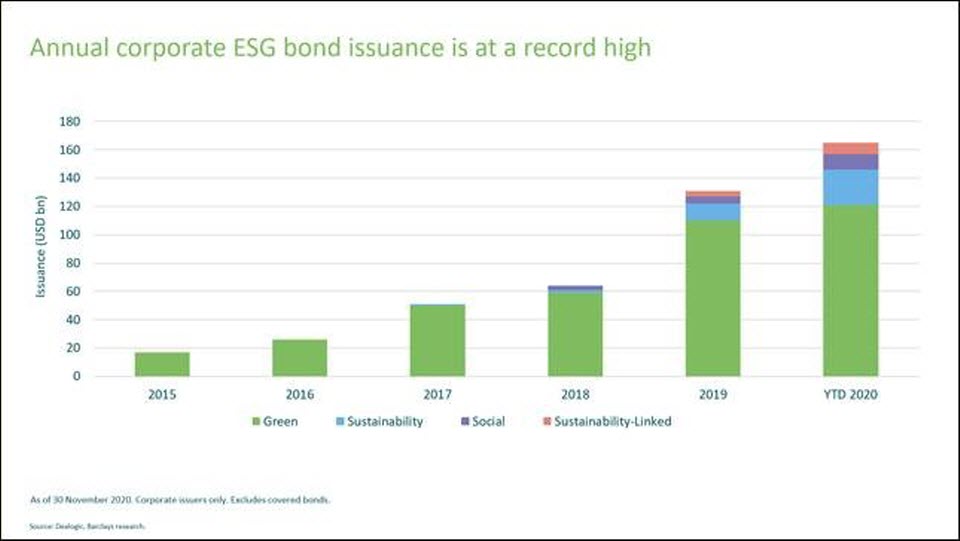

The past five years have seen an exponential increase in investors’ ESG awareness, and corporate issuers are increasingly finding new ways to take advantage of the demand for sustainable investments. In the world of fixed income, one concept which has gathered plenty of attention has been the growth of green bonds.

While most investors are now familiar with these bonds, they are by no means the only way to gain exposure to ESG-labelled bonds. Recently, corporate issuers have sought innovative ways to access increasingly ESG-conscious capital markets, with new concepts such as transition bonds and sustainability-linked bonds. And over the past year, COVID-19 has brought a new need for governments and companies to mitigate social risks, leading to the rapid rise of social bonds in 2020.

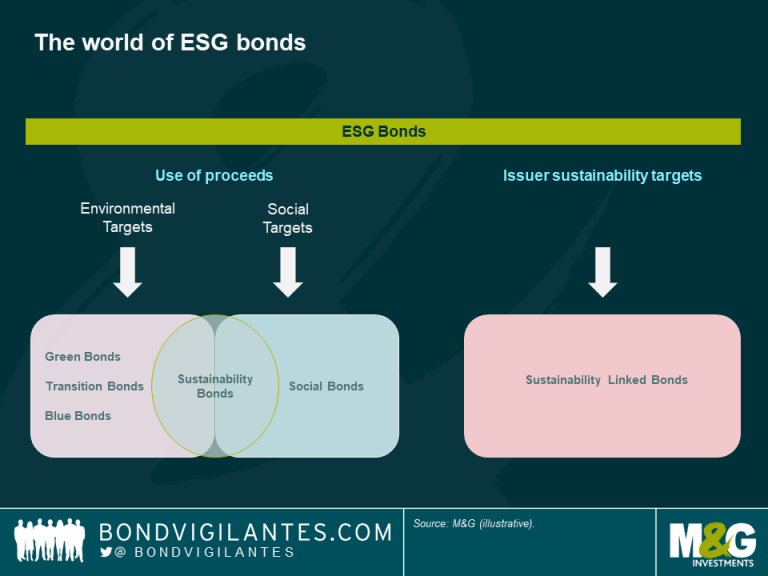

The first thing to note is that most ESG bonds are characterized by their targeting ESG-friendly projects with their proceeds: the issuer itself does not necessarily need to have strong ESG credentials. Having said that, it is becoming increasingly difficult for bond issuers to access the market with ESG-labelled bonds when their corporate strategy is misaligned with those objectives.

Secondly, it is a market which is self-labelled: following governance and reporting practices set by bodies such as the International Capital Markets Association (ICMA) is voluntary. This means that bond investors need to perform some due diligence to ensure that the ESG targets set are in the spirit of their investment philosophy.

Enough of the technicalities for now. Let’s explore the various forms of ESG bonds which are continue to take up market share.

Green bonds

Green bonds are the most established part of the ESG bond market. The proceeds of these bonds finance environmentally-friendly projects such as renewable energy projects or electric vehicle charging stations. Last year saw green bond issuance of as much as $182 billion, including some inaugural emerging market (EM) issuers like Egypt (which became the first country in both Africa and the Middle East to issue a dollar sovereign green bond). Such issuance from EM and high yield issuers adds welcome diversity to the green bond universe, which is still tilted to highly-rated issuers, predominantly banks and utilities.

I expect the green bond market to grow even further in 2021 and beyond, boosted by the European Green Deal, China’s pledge last year for carbon neutrality by 2060, as well as US President-elect Biden’s $2 trillion green energy and infrastructure plan – the latter now supported by the Democrats’ control of the Senate. Furthermore, ECB members have mentioned more than once that climate change is a price stability risk and therefore a primary objective for the European Central Bank. With monetary and fiscal policy being increasingly joined-up in Europe to tackle the challenges of the zero bound, some form of green bond QE cannot be ruled out either.

Social bonds

The proceeds of social bonds go to projects with positive social outcomes such as providing access to education, affordable housing or improving food security. According to the ICMA principles, such social projects can also include COVID-19-related healthcare and medical research, vaccine development and investment in medical equipment. It comes as no surprise that social bond issuance in 2020 surged to fight the pandemic. In April 2020, Guatemala became the first country to issue a sovereign social bond aimed at financing COVID-19 response efforts. Corporate social bond issuance is on the rise as well as pictured below.

With consumers now more attuned to social issues, social bonds provide companies with an instrument to demonstrate support for their wider stakeholders, from employees to customers and local communities. In 2020, social bond issuance reached $78 billion, an increase of 900% versus the previous year. As highlighted by S&P in a recent research note, the growing nature of such bonds does come with challenges for the industry. As opposed to green bonds, where quantitative improvements can be traced fairly easily, the outcomes targeted by social bonds are more qualitative in nature. This makes monitoring the impact of social bonds challenging and calls for improved reporting and disclosure practices to prevent so-called social washing – the practice of an issuer misrepresenting the social impact of its financed projects.

Sustainability bonds

Sustainability bonds are used to finance a combination of green and social projects. These bonds made headlines in August last year, when Google’s parent company Alphabet issued a multi-tranche deal worth $5.75 billion. The issue was the largest sustainability deal in history and catapulted Alphabet up to become the second-biggest sustainability bond issuer, accounting for 8% of the sustainability bond market. The proceeds of this deal will be used for environmental projects, such as making Google data centres more energy efficient, mitigating carbon emissions linked to transportation or maximizing the reuse of finite resources across operations, products and supply chains. Social projects include building at least 5,000 affordable housing units or providing financing for small businesses in Black communities.

Transition bonds

These ESG bonds are securities issued with the purpose of enabling a shift towards a greener business model. In particular, they are an instrument which allows so-called brown industries to transition towards a greener future. As I have argued in a previous blog on transition bonds, achieving a low-carbon world requires existing businesses, and in particular brown industries, to decarbonize and mitigate climate risk. While it would be a stretch for a coal-heavy utility company to issue a green bond, a transition bond can be used to accelerate investments towards a greener future.

As with green bonds, social bonds and sustainability bonds, transition bonds have the advantage of defined use of proceeds. This could open a wider investor base for energy companies that use the framework of transition bonds for low carbon activities such as renewables, green hydrogen or Carbon Capture, Utilisation and Storage (CCUS). In 2020, I counted four such transactions from three issuers. Those include Cadent Gas (the UK’s first transition bond), Etihad Airways and Italian gas transportation business Snam, the latter issuing transition bonds twice last year.

Blue bonds

Blue bonds are a subset of green bonds, those used specifically to finance projects related to ocean conservation. This includes managing plastic waste, but also promoting marine biodiversity by ensuring sustainable, clean and ecologically-friendly developments. As with green bonds, blue bonds follow the associated ICMA principles. Blue bonds are probably the most niche of the ESG bonds I survey: at the end of 2020, we have still seen only the fourth blue bond ever issued globally, following issuance from the Seychelles in 2017, and the Nordic Investment Bank and the World Bank in 2019.

Last year’s issuance from the Bank of China was a landmark, as the $942.5 million-equivalent deal was both the first blue bond from the private sector and also the first blue bond from a commercial bank. Whether this will be the catalyst for more blue bond deals remains to be seen. However, considering our growing global population, rising sea levels and change in dietary habits, it wouldn’t surprise me to see more activity in this area as our reliance on sustainable oceans is set to increase. Already, the market value of marine and coastal resources and industries is worth $3 trillion per year or about 5% of global GDP as estimated by the United Nations.

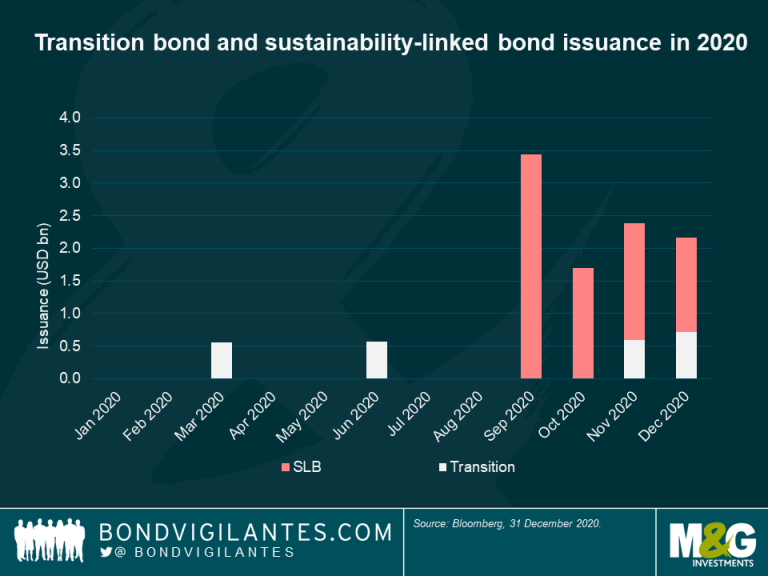

Sustainability-linked bonds

Sustainability-linked bonds (SLBs) work somewhat differently in the sense that there are no restrictions on the use of proceeds. What matters here is the company’s meeting certain predefined sustainability targets which can be related to environment or social aspects. Hence, it is an approach that moves away from specific activities and puts in focus the sustainability performance of an issuer. The coupon of sustainability-linked bonds is linked to some sustainability performance indicators – not meeting the sustainability commitments would result in a coupon step-up.

This is the ESG bond structure to which I would assign the biggest growth potential for the coming years. The lack of restrictions gives the issuer more freedom on how to spend the proceeds and lets the issuer pursue high profile goals on a company level, such as alignment with the Paris Agreement. SLBs are also more inclusive to issuers than the usual Use of Proceeds structure, and can work well for smaller companies and those in ‘dirtier’ sectors that have been unable to access certain parts of the Use of Proceeds market. The flip side to this is that lenders have no certainty on how those proceeds are spent – they could even end up supporting carbon activities. SLBs require a look beneath the surface to ensure that the performance indicators set are ambitious enough to tackle climate risk, as highlighted by my colleague Charles de Quinsonas in a recent blog.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

18 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox