It’s time to talk about European QT – part 1

There has been a notable shift in tone from several ECB speakers over the past couple of weeks in that they are talking more explicitly about shrinking the ECB’s balance sheet (known as quantitative tightening or QT) in what looks like a coordinated attempt to prepare the markets for the ECB’s next phase of monetary policy.

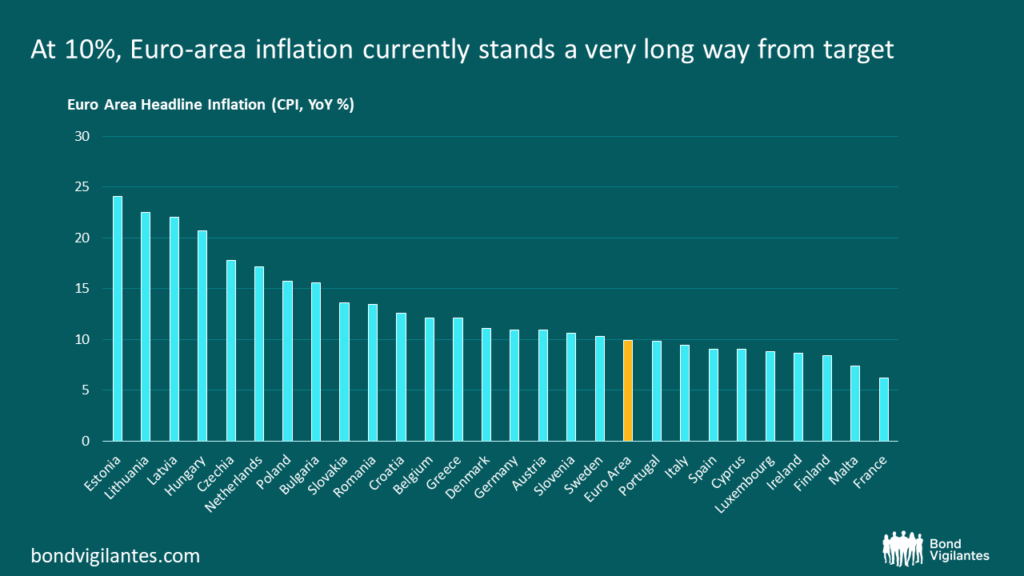

Euro-area inflation currently stands at 10% – a record for the single currency. Germany hasn’t seen this level of inflation since 1951 (during the Korean War). Before the pandemic, the proportion of items within the inflation basket that had inflation above 2% stood at 25%. That figure has now jumped to 85%. Moreover, headline inflation also masks a deep dispersion within Europe, ranging from 6.2% in France to well over 20% in the Baltics (Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia). This is a very long way from the ECB’s mandated 2% target.

Source: M&G, Eurostat (September 2022).

While headline inflation is expected to fall next year as energy and food inflation drop off, core inflation (now at 4.8% yoy) is expected to remain strong, broad-based and self-reinforcing. This latter point is the real concern. In a simple world, tighter financial conditions slow demand for goods and services, which in turn should slow growth and cure inflationary forces. The real world is not so simple. European countries are reacting to inflationary pressures (mainly caused by spiralling energy costs) with huge fiscal spending plans, while at the same time the euro has been depreciating (down ~14% vs US dollar year-to-date). Both these factors reinforce inflation as growth weakens.

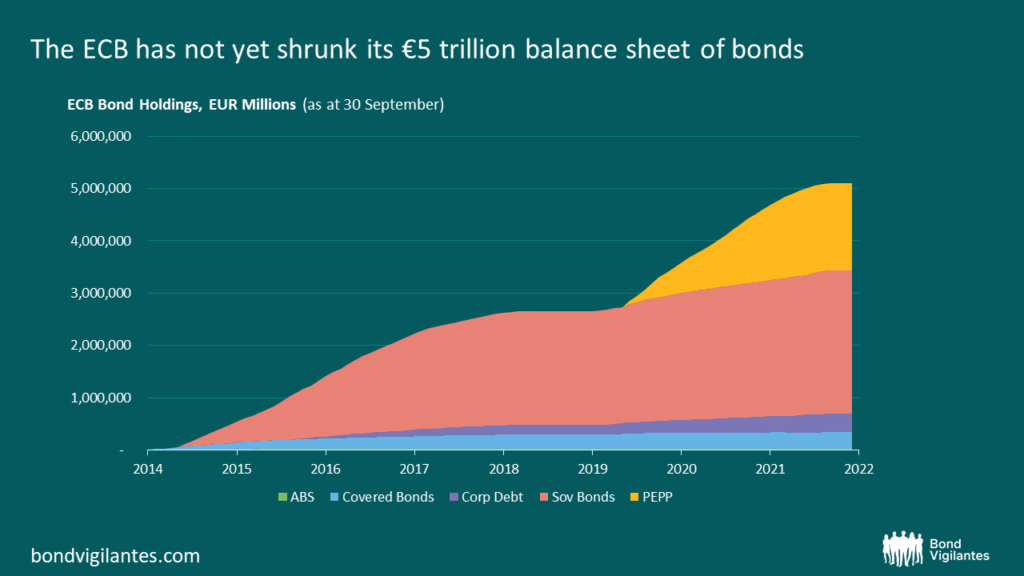

At the time of writing, the ECB has tackled inflation by hiking interest rates twice this year, taking its deposit rate from -0.5% to +0.75%. A further hike of +0.75% is expected on 27th October. Yet the ECB’s €5trn balance sheet of bonds remains unchanged. These assets were accumulated through quantitative easing (QE), a monetary policy tool used to stimulate spending in the European economy, starting back in 2014 and then turbo charged in 2020 to support the economy during the Covid pandemic. It worked by printing huge amounts of euros, which were used to buy bonds from the private sector. The ECB stopped increasing the amount of bonds it bought in July of this year, although proceeds from maturing bonds are still reinvested into new bonds with the same characteristics, maintaining the overall balance and shape of the portfolio. Given QE was part of the mechanism that stimulated the economy which, in turn, led to high inflation, it is reasonable for policy makers to consider when QT will form part of the monetary solution to extinguish it. (See here for more on QE and QT).

Source: M&G, ECB (30 September 2022)

There are other good reasons why the ECB should look to unwind its bond holdings. For one, there is growing evidence that European funding markets are suffering from a scarcity of German government bonds, the highest quality and usually most liquid form of collateral. Shortages are frequently pushing repo rates negative (meaning you get paid to borrow money), a phenomenon that occurs when demand for high-quality collateral outstrips demand for cash. This is also related to the historically wide spreads between swap rates and bund yields. The ECB currently owns approx. 60% of all ECB-eligible German Government debt outstanding (40% in APP(PSPP) and 20% in PEPP). In theory, these bonds should be available to repo markets, but this transmission mechanism does not appear to be working properly.

There is also the negative impact that both falling bond prices and rising financing costs will have on national central bank capital positions, as highlighted by the Dutch central bank in its recent ‘profit warning’ (see here).

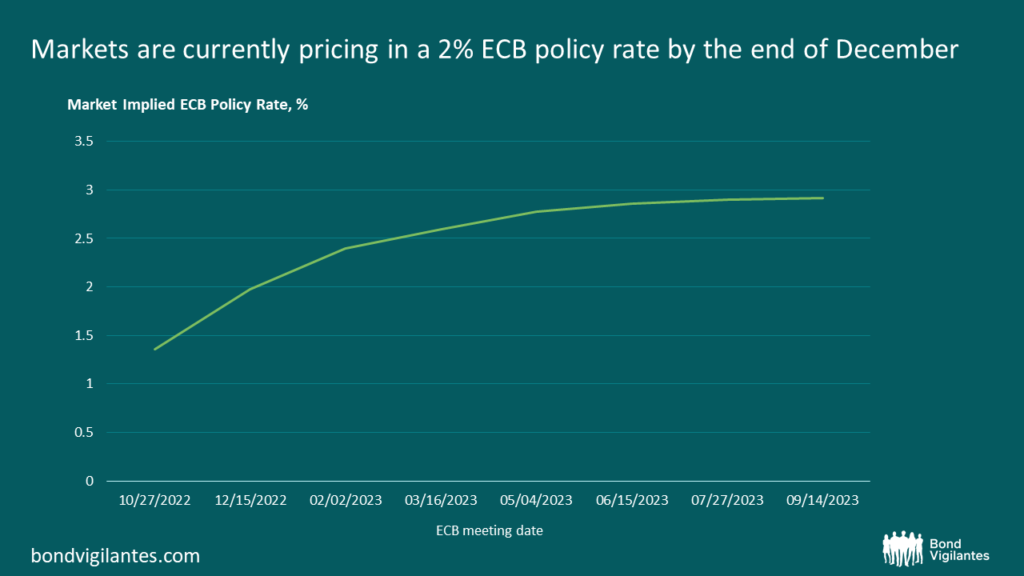

In terms of timing, ECB President Lagarde recently said that the ECB would consider unwinding its balance sheet once policy rates had ‘normalised’. Many economists consider the ECB’s normal or neutral rate to be somewhere near 2% which markets are currently pricing in by the end of December 2022. By implication, QT could start as soon as Q1 next year.

Interest rates will remain the ECB’s primary tool to tighten financial conditions and fight inflation, but the case is growing for balance sheet reduction to work in tandem. Naturally this poses risks for market stability and fragmentation, presenting investors with a challenging environment to navigate over the coming quarters.

In this multi-part blog edition, I will drill down more into this topic to discuss how European QT could be structured and what the implications are for periphery spreads, credit, swap and collateral markets.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.