Housing market timebomb – is Sweden just the start?

Housing market woes became a hot topic in 2022, with interest-rate hikes meant to combat accelerating inflation putting pressure on house prices globally. Combined with high starting levels for property values after the post-pandemic housing boom, many are predicting further declines going into 2023. Real estate downturns (defined as two consecutive quarters of falling prices) have been triggered in a number of economies including Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the Nordics.

One area where this trend is playing out most rapidly is Sweden, where house prices are falling at one of the fastest rates in the world. Whilst there are multiple reasons why the Swedish market is particularly vulnerable to the economic backdrop, it is a major warning sign to other economies in showing how quickly high rates can wipe the floor out of a housing market.

What is happening?

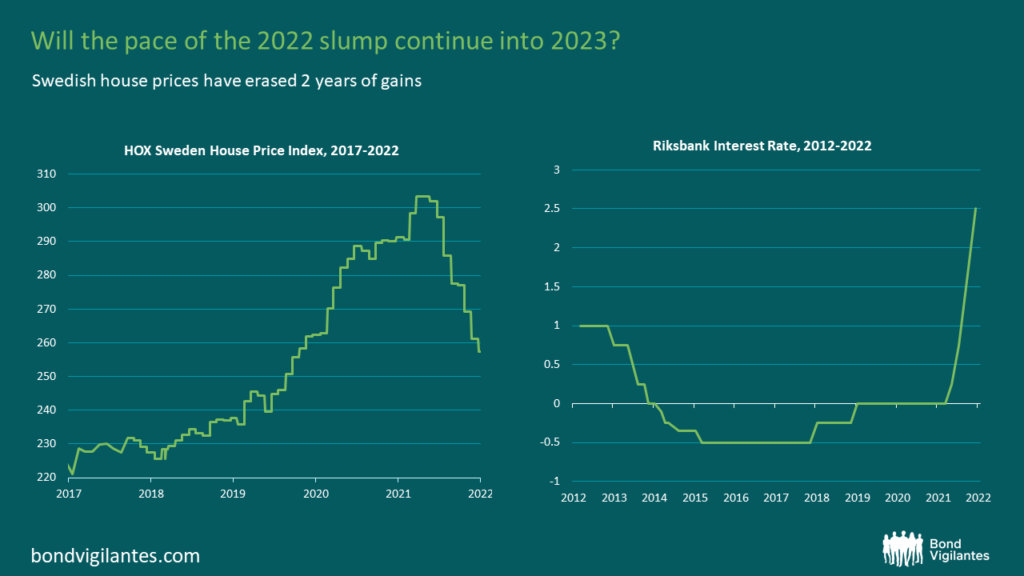

As the world emerges from an era of cheap credit and as ultra-loose monetary policy is reversed, ballooning debt and a rise in the cost of living have led to nine months of sustained losses for Swedish home values. House prices are now down around 15% from their 2022 peak (and apartment prices by 14%), with many economists expecting a 20% peak-to-trough decline in the HOX Valueguard index (which combines apartments and houses). Some are even saying this is too conservative.

The rate at which prices are sliding is one of the fastest in the world, and is at levels comparable to the early 1990s, when Sweden was rocked by a property crash that spilled into its financial markets and forced banks on the brink of default to be taken over by the government. The Riksbank has raised its key interest rate to 2.5% from zero since April last year, but the central bank may have further to go as Sweden’s inflation rate reached double digits in December (the first time in over 30 years), and labour markets remain stable for now. The triple whammy of mounting costs of living, higher borrowing costs and falling home values is creating economic pain, with Sweden now at risk of falling into the worst recession in the EU.

What was the starting point?

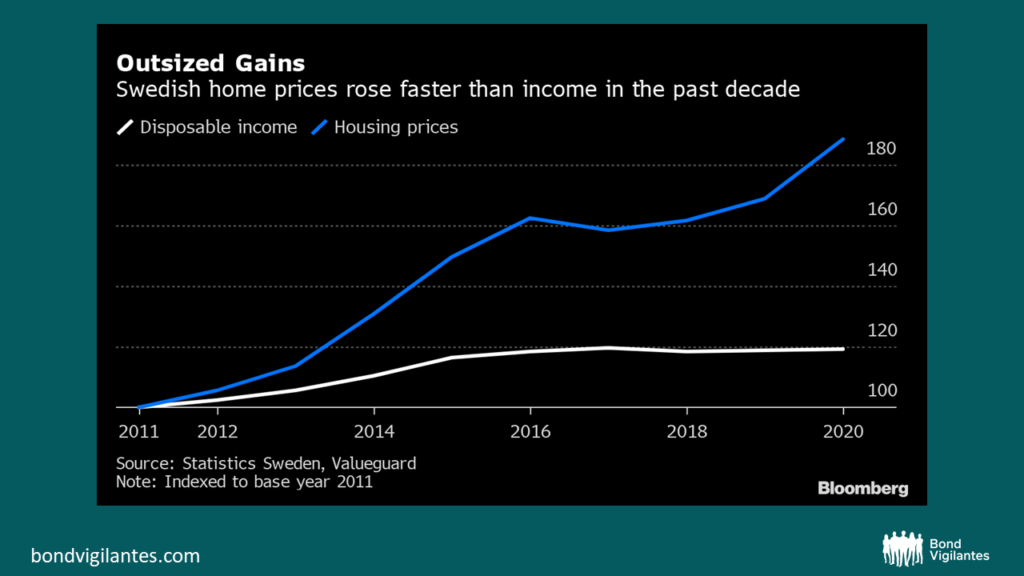

It is worth pointing out that one reason why Sweden is experiencing such a housing market slump is that it has long been one of Europe’s hottest housing markets. An enormous boom during the pandemic added to an already high level of house price growth over the last 10 years. Home values were driven up by a shortage of housing, years of low interest rates and by mortgages that only required interest payments for years. New regulations in 2016 introduced amortisation requirements, but the majority of households are still only obliged to pay down their debt to 50% of property values. The result was price increases that outstripped GDP growth and wage growth, leaving home owners deep in debt.

Why is Sweden particularly vulnerable?

Swedish homeowners are particularly exposed to the pressure of higher rates for numerous reasons. Firstly, Sweden has extremely high levels of household debt – 200% (of annual disposable income) on average in 2022 (OECD), up from 150% 15 years ago. This seemed easier to sustain during the years following the financial crisis when the Riksbank lowered rates: for the past 7-8 years, the bank has set them at zero or negative.

Secondly, the majority of mortgages in Sweden are on variable or short-term fixed rate deals, so these higher rates filter through rapidly into higher costs for homeowners. More than 40% of mortgages reset their rates in 3 months or less, and only 18% are fixed for 3 years or more. Around 60% of homeowners have a mortgage, and around half of them will need to refinance this year. In a market that was used to refinancing frequently, this transmission is expected to have a dramatic effect on consumers’ finances. On top of this, Sweden has the lowest level of fiscal support by GDP in Europe, so the government offers relatively little protection against a backdrop of not wanting to further stoke inflation.

Is this a warning to other economies?

Whilst the pace of the plunge is alarming, it is not all bleak. Sweden does not have a buy-to-let market, for example, which reduces the volatility of house prices. A shortage of housing should also provide a cushion in many local markets. The central bank has also said that it is more concerned by highly indebted property companies and the commercial real-estate sector than by household debt burdens. Starting points also matter, and markets have some cushion before we reach pre-pandemic price levels.

Having said that, other economies like the UK also experienced an enormous housing boom during the pandemic. Like Sweden, mortgage offers here also typically last around 6 months, meaning purchasers whose offers have expired have found their budgets suddenly reduced and lenders quickly tightening their affordability requirements. Other economies are also battling many of the same global factors affecting Sweden, namely soaring energy bills, falling real wages and a worsening economic outlook. Whilst homeowners here are slightly protected by the larger share of mortgages on fixed-rate deals, it is clear that the pace of the Swedish housing market slump is a major warning sign. Housing markets globally could be the big hurdle to central banks raising rates enough to tackle sticky inflation.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.