Sukuks: a market that rewards those willing to trust the technicals

How should one approach investing in sukuks – Sharia-compliant bond-like instruments – as a manager of conventional funds? The recent issuance of an Additional Tier 1 (AT1) capital instrument by Abu Dhabi Islamic Bank (ADIB) provides us with an excellent case study of the problems we face when investing in this market. This deal, callable in early 2029, priced at a yield of 7.25%, which equates to a spread of roughly z+340bps. This seemed expensive as it was in line with where Emirates National Bank of Dubai (ENBD)’s AT1 paper was trading, while ENBD’s bond is callable two years earlier and the bank is larger and has a higher stand-alone credit rating. All of which meant that the market was taken completely by surprise as ADIB’s new issue rocketed from par to 104 in just a day, ending up trading at z+248bps – a more expensive level than the AT1s issued by national champion First Abu Dhabi Bank (FAB) callable in 2026. The reason? The ADIB bond is a sukuk, whereas the ENBD/FAB bonds are conventional.

The sukuk market behaves completely differently to conventional international bond markets. There is a very strong local bid, mainly from the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). The pool of Islamic assets available to sukuk funds is relatively small, meaning that they are forced to accept tighter pricing than conventional funds. Liquidity is a further issue, as sukuk paper tends to get held to maturity. Again, the ADIB deal is instructive here: just two days after the issuance of this $750m bond, it is being quoted only in very small sizes. In the case of bank paper, the banks often boast extensive private banking networks that are willing buyers of their bonds, since retail clients often see subordinated bank debt effectively as senior risk that offers high returns.

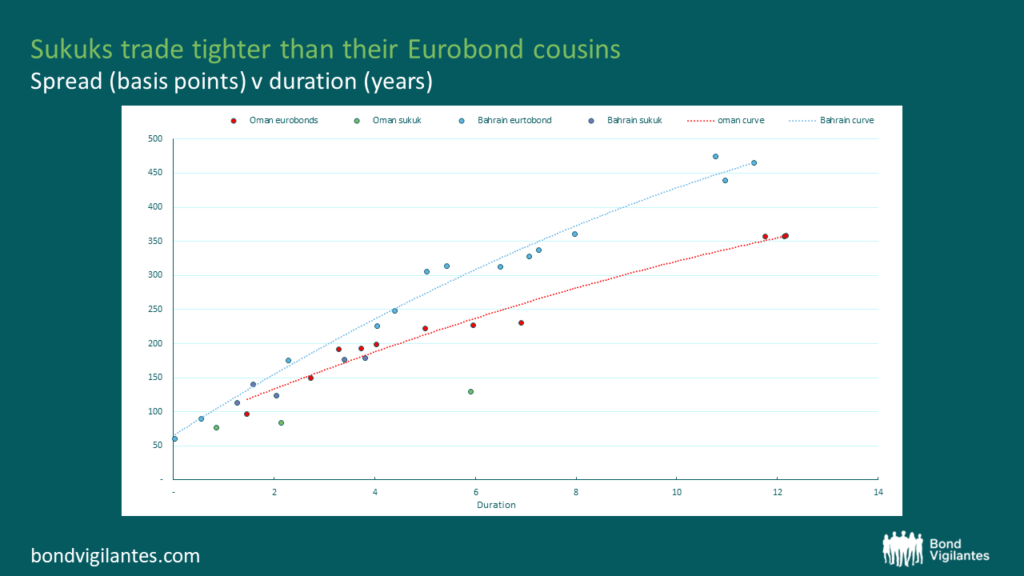

Importantly, these dynamics are not confined to more niche bank subordinated debt, but are also evident in some higher-yield sovereign curves. For example, Bahrain and Oman sovereign sukuks trade a little tighter than their conventional equivalents as they tend to appeal to different types of investor (see chart). However, this is in contrast to the IG case of Saudi Arabia, where sovereign sukuks trade in line with standard eurobonds. This underlines how regional politics and varying credit ratings also contribute to a certain fragmentation of the market.

Source: M&G Investments, Bloomberg (July 2023)

Managers of conventional funds therefore face a problem. Should they ignore new issues that look much too expensive, potentially forfeiting several points of upside? Or should they hold their noses, have faith in the strong technical behind the sukuk market and participate in deals that will become illiquid very quickly? Our feeling is that we should be less demanding on pricing for sukuk new issues and look to participate, with two caveats: only in small size (to mitigate liquidity risk) and only in very high-conviction names (in case the bonds cannot be sold if something goes wrong). Importantly, this applies only to new issues; both pricing and liquidity favour buying conventional bonds in the secondary market.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.