Six scary charts – happy Halloween!

This blog first appeared in the Financial Times

It’s Halloween again and time for the Bond Vigilantes’ yearly round up of the spookiest charts in global finance.

With persistent levels of inflation and increasing signs of weakness in the global economy, 2023 has been a scary year for everyone. Turning our focus to markets, the effect of higher financing costs following central banks’ aggressive tightening of monetary policy has meant we have found no shortage of scary charts either.

Happy Halloween!

- Duration can be scary

Source: Bloomberg, M&G, Swiss Re/Jack Farley (October 2023)

With the release of pent-up demand following lockdowns, and with excess money in the economy as a result of stimulative monetary and fiscal policy during that period, the past few years have seen inflation make a comeback. As markets have repriced their inflation expectations and as central banks have aggressively increased interest rates, investors in longer-dated bonds have had a sharp reminder that duration can be scary.

Bonds with higher duration leave investors exposed for longer to the risk of inflation eroding the real value of their investment, which is why they tend to suffer in such environments. This chart really puts the moves in bonds since the pandemic into perspective: the total drawdown in long-duration US Treasury bonds now exceeds the peak-to-trough stock market crash seen in the Great Financial Crisis.

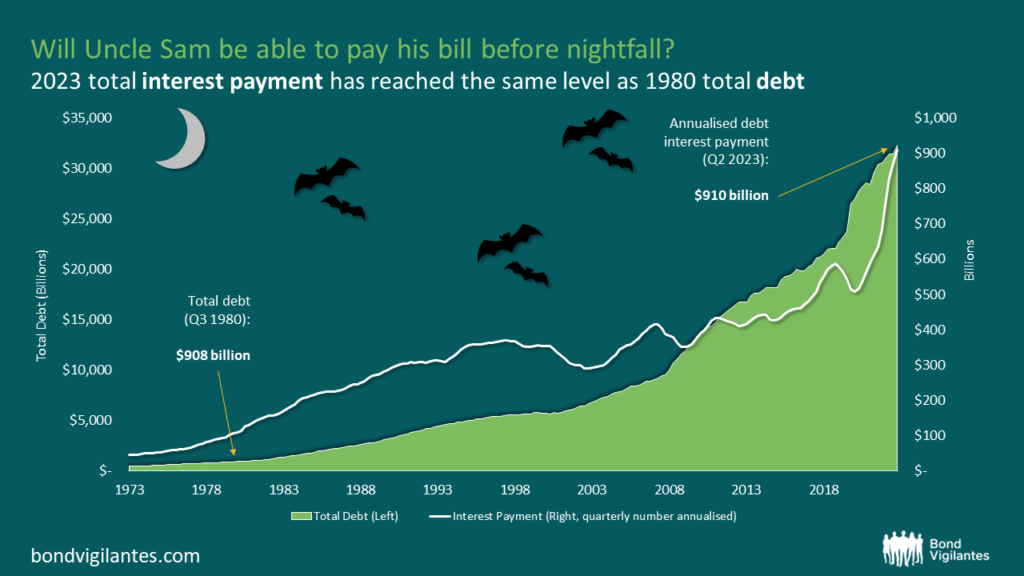

- Will Uncle Sam be able to pay his bill before nightfall?

Source: Bloomberg, M&G (June 2023)

Uncle Sam has a big bill to pay. The combination of significant borrowing during the pandemic, together with the rise in interest rates means that debt interest payments have been rising fast for the US government. Annual interest payments look like they will soon hit $1 trillion, and likely rise even further as maturing debt will need to be refinanced at higher rates. In fact, total interest payments for the US have now reached the same level as their total debt in 1980!

There is a risk that rising Treasury bond supply and higher leverage will spook investors: perhaps the recent US downgrade by Fitch will not be the last. While default is highly unlikely, the increasing risk of US Treasuries is likely to be manifested primarily at the long end of the curve as market participants demand a higher term premium.

- Midnight approaches following curve inversion

Source: Bloomberg, Citi Velocity, M&G (October 2023)

The inversion of the US Treasury curve is a well-known signal that a recession is on the way. For many decades, a recession has always followed in the months following inversion. An inverted yield curve refers to the situation when short-term yields are higher than long-term yields, indicating that investors are repositioning into longer-dated bonds and suggesting market pessimism on near-term economic prospects.

But a closer look at the chart above reveals that it is in fact when the curve starts to steepen again following an inversion that recession usually strikes. With the 2s10s curve (10 year yield minus 2 year yield) having just started to steepen, is midnight nearly upon us?

- Will higher financing costs bite high yield issuers?

Source: Bloomberg, BofA Merrill Lynch, M&G (August 2023)

We are now 18 months into the hiking cycles of most central banks. Despite this, credit valuations have remained resilient, even within high yield bonds. The (option-adjusted) spread of the Global High Yield index has now fallen to the low 400s (bps), leaving it at close to its tightest levels since the Great Financial Crisis.

No doubt high yield credit spreads have been helped thus far by demand from yield-hungry investors, and also tighter supply of high yield bonds: high yield issuers have refrained from refinancing where they can in light of higher funding costs.

But, with many companies having put refinancing off for some time now, maturity walls are closing in: nearly 10% of high yield issuers face refinancing risk in the next two years. This is likely to become the largest refinancing effort for HY issuers since the GFC.

- Sharks lurking beneath the inflationary waters

Source: M&G, Bloomberg (September 2023)

Inflation usually comes in waves. This is perhaps because it tends to cause issues that governments and central banks try to resolve with expansionary policies.

For example, back in the 70s we had two big waves of inflation before then-Fed Chair Volker finally managed to put the inflation genie back in the bottle. With inflation dynamics looking similar to the ones we experienced in the 70s, there is a risk that inflation could make a comeback.

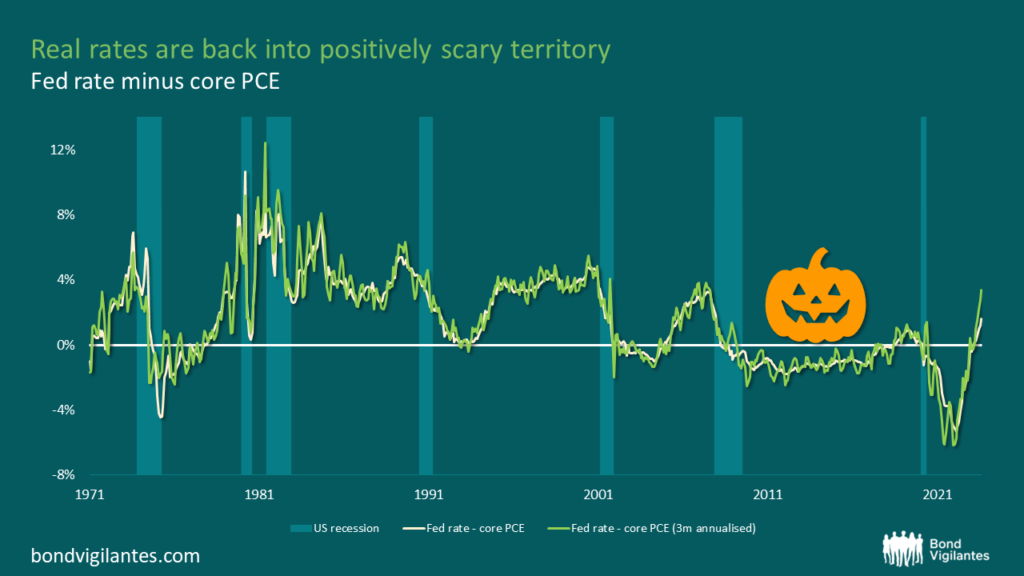

- Real rates are back into positively scary territory

Source: M&G, Bloomberg (31 August 2023)

The risk of recession is increasing. One of the key indicators we follow is the real rate, which we have defined in the chart above as the central bank rate minus core inflation. In the US, a real rate above 3% has traditionally been a precursor to recessions.

Real rates have been rising significantly over recent months and, following central banks’ tightening of monetary policy, now sit comfortably within positive territory. On a year-on-year basis, real rates are now approaching 2%. Looking at more recent inflation dynamics, however, real rates just crossed the 3% mark.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.