What The Fed? When rate cuts don’t make sense and debt redefines the rules

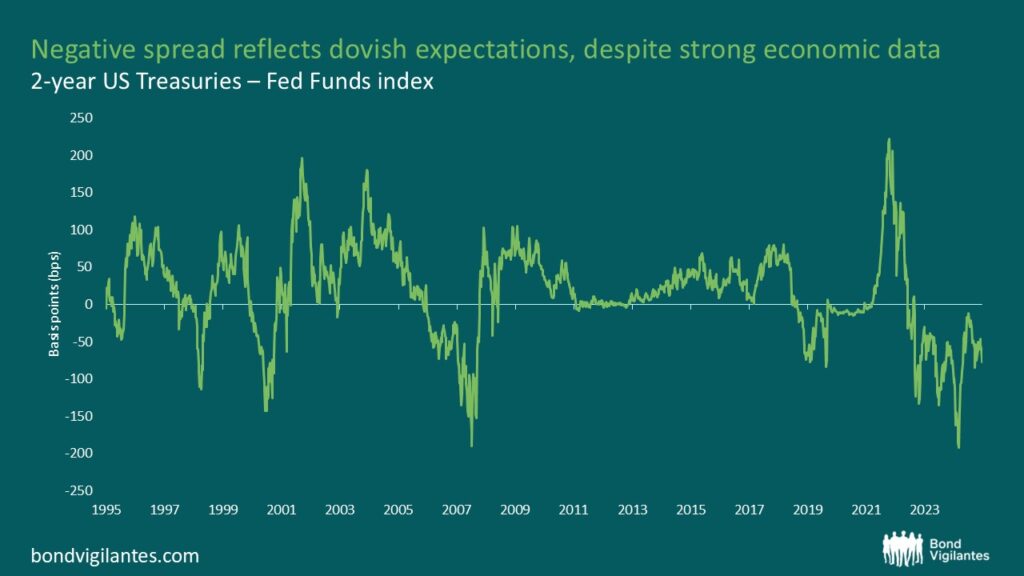

Markets are once again high on ‘hopium’. Despite a still-strong labour market, sticky inflation, and an economy that refuses to roll over, rate cut bets have surged back into vogue. The Federal Reserve might be saying “higher for longer,” but investors are dancing to a different beat. Why is the market so convinced cuts are coming when the data tells a different story?

The disconnect: strong data, dovish pricing

Let’s start with the basics. The US economy continues to defy gravity:

- Unemployment is near historic lows.

- Core inflation remains above the Fed’s 2% target.

- Consumer spending is showing resilience, even if cracks are emerging.

- Wages are still growing, and the services sector refuses to cool.

- Risk assets are elevated (credit spreads are tight and equities are at highs).

- The Atlanta GDP estimate is now at 2.8% in real terms.

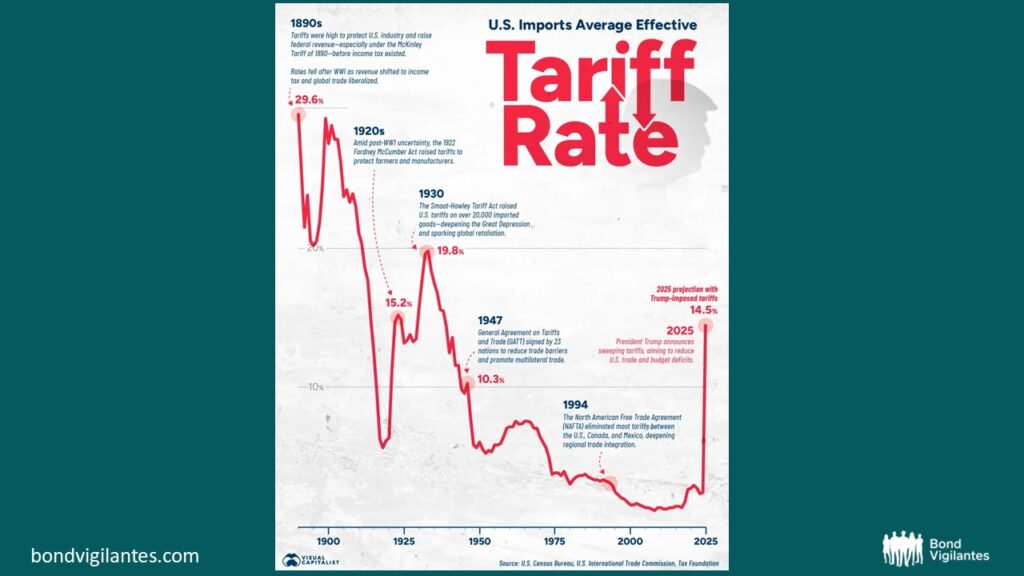

- Although tariffs have been meaningfully reduced, the net effective tariff has increased from approximately 2% to 12%, and the impact of this change is yet to be felt.

Source: Visual capitalist, US Census Bureau, US International Trade Commission, Tax foundation

And yet, futures markets are entertaining the idea of 150 basis points in cuts by the end of 2026. You’d be forgiven for thinking a recession was imminent, but the data simply doesn’t support it. There is no clear and present danger requiring immediate monetary easing. It appears as though an asymmetry is creeping into the market.

Source: Bloomberg

A caveat on the impact of this monumental change in tariffs is that they will impact both inflation and growth going forward, muddying the waters and making the Fed’s job even more challenging.

So why the divergence?

Have markets lost faith in the Fed’s reaction function?

The Fed’s traditional response function (think Taylor rule) is simple: respond to inflation and unemployment. But what if that framework is breaking down? What if the central bank is now facing a third variable it can’t ignore: government debt sustainability?

Public debt-to-GDP has ballooned. Servicing costs are rising fast. Higher rates have doubled (or more) the cost of new borrowing. The question is no longer just “is inflation too high?” or “is growth slowing?”, it’s becoming: “can we afford to keep rates this high?”

Is the Fed becoming politicised, and having its hand forced by the high debt load?

There’s a growing theory that debt sustainability is starting to influence monetary policy, if not overtly, then tacitly:

- Net interest costs are now the second largest expenditure item after social security.

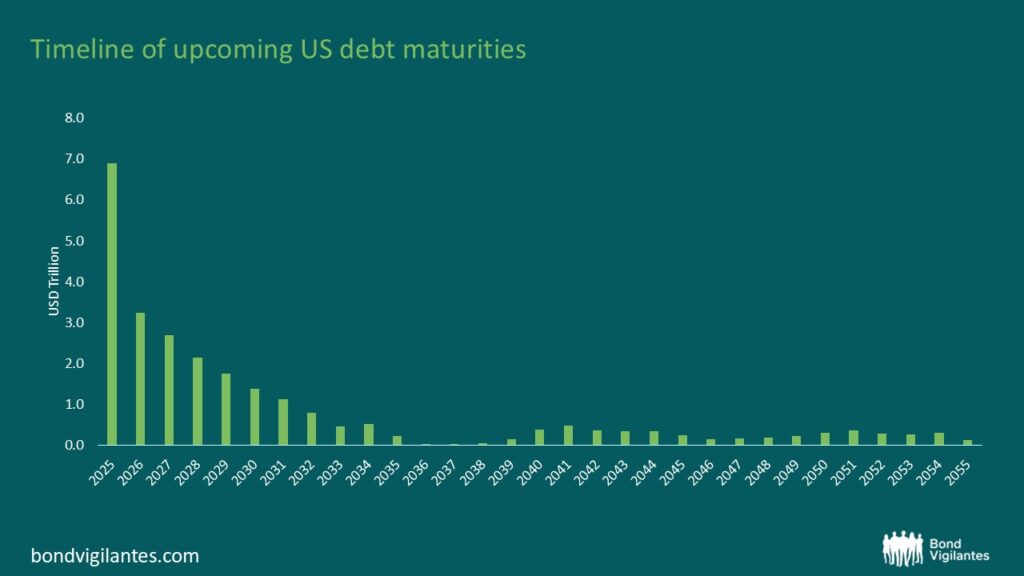

- The higher rates go, the higher the interest expense becomes. Let’s not forget that the US government needs to roll c.$10 trillion in debt over 2025 and 2026 (see chart below). This amount is significant, possibly more so as US exceptionalism is increasingly being questioned.

- There’s political pressure to “do something”, and cutting rates is perceived as easier than raising taxes or slashing spending. Given the US’s exposure to rollover risk1, the government will benefit significantly from lower administered rates.

- Donald J. Trump has heaped schoolground pressure on ‘too late Powell’, threatening to fire him: “I can do a better job, perhaps I should”, “he’s a loser, not very smart”.

- Lining up a ‘shadow Fed chair’ will likely render Powell’s final months redundant, or at the very least, make his job more difficult. With Powell’s position of Fed chair coming to an end in May 2026, much more weight will be placed on his successor. In fact, some hopefuls have been dusting off their CVs and calling for rate cuts despite the data, no doubt raising their standing in Trump’s eyes.

Source: Bloomberg

While the Fed remains technically independent, the economic reality is putting it in a box. Rate hikes were politically feasible when inflation was the villain, but as that narrative softens, so too does the Fed’s room to manoeuvre.

This raises a disturbing possibility: maybe the market isn’t mispricing rate cuts, maybe it is betting on fiscal dominance and a more politicised Fed. That is, central banks may eventually bow to the needs of the government balance sheet and the wants of an incumbent government, rather than to strict macro fundamentals.

What The Fed does next may no longer be about data alone. It may be about debt. If so, we’re entering a new regime: one where traditional models of inflation and employment lose their predictive power, and monetary policy becomes a servant, not a master.

So when the market prices in cuts against a backdrop of strong economic data, maybe it’s not madness. Maybe it’s a grim kind of foresight: the Fed is trapped, and the old playbook has been thrown out.

One thing’s for sure: if the Fed is no longer fighting inflation, but instead grappling with the math of Treasury auctions, then it’s not just rates that need re-pricing, it’s the entire framework we’ve relied on to understand monetary policy for the last 40 years.

1 Rollover risk refers to the potential difficulty / increased cost a borrower may face when refinancing or renewing maturing debt.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.