Monetary policy and government independence: The legacy of Quantitative Easing

The standing economic orthodoxy is that Independent central bankers are adamant in their belief that their remit is purely monetary and that governments are in charge of fiscal policy.

Though at times of stress, it is well recognised that central banks should act in a coordinated fashion with national governments. This has rightly occurred across many jurisdictions since independent central banks became the common framework in developed economies towards the end of the last century. We are now not in an emergency, so central banks are once again allowed to operate their monetary levers independently of national governments. The legacy of quantitative easing (QE) has, however, left an interesting legacy for central banks in this relationship. This is best typified by the Bank of England and this is the topic we will focus on below.

The spillover effects of QE under different interest rate regimes

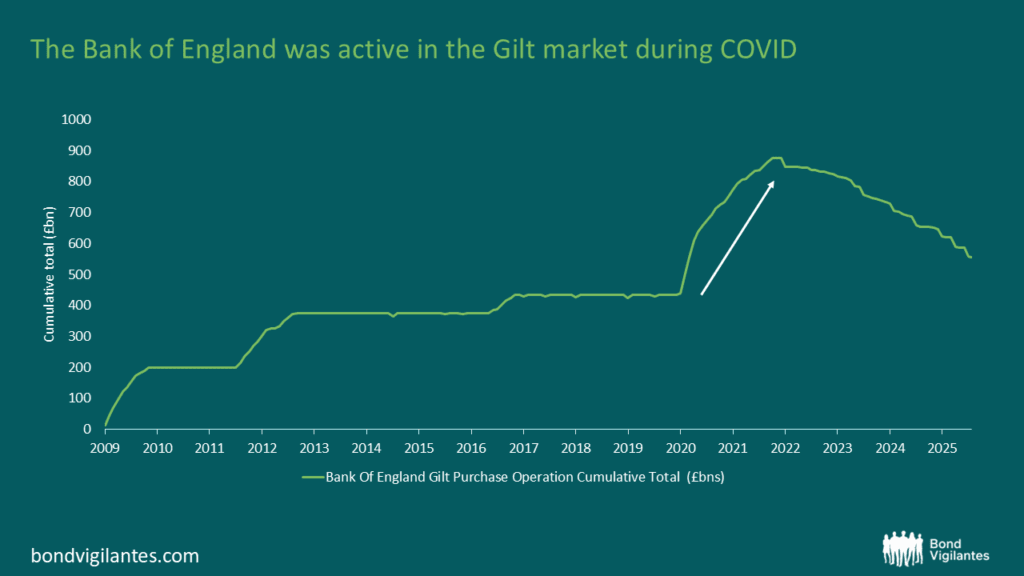

The UK was amongst the most active in altering its day-to-day economic life during COVID. The UK’s central bank, the Bank of England (BoE), also pursued an index approach of printing money via purchasing fixed interest securities across the length of the yield curve, in broadly equal buckets. The BoE was therefore the most heavily involved in buying long-dated debt to facilitate the creation of money.

Source: M&G, Bloomberg

During the low-interest rate phase of QE this resulted in excess income for the BoE, which was essentially borrowing at short-term interest rates by printing money, and lending at long-term interest-rates by buying gilts. In this scenario there was a benefit from the yield advantage generated by buying bonds at higher yields than the short-term financing rate. This excess income, and the occasional capital gain when a gilt redeemed, was repatriated to the government’s finances. Hence, QE not only reduced interest rates but also helped government finances. The independent central bank was stimulating the private sector directly through monetary policy, and indirectly by creating fiscal headroom by reducing the budget deficit, thereby creating fiscal headroom for tax cuts or higher spending for the government.

Given the increase in both short- and long-term interest rates post COVID, this carry trade has turned negative. Gilts that were bought with low yields are now being financed by borrowing at a much higher cash rate. This results in an income loss that means the government ultimately has less fiscal room, as they need to refill the BoE’s coffers.

Quantitative tightening (QT) brings this negative carry loss into the present day.

The impact of monetary policy on budget deficit

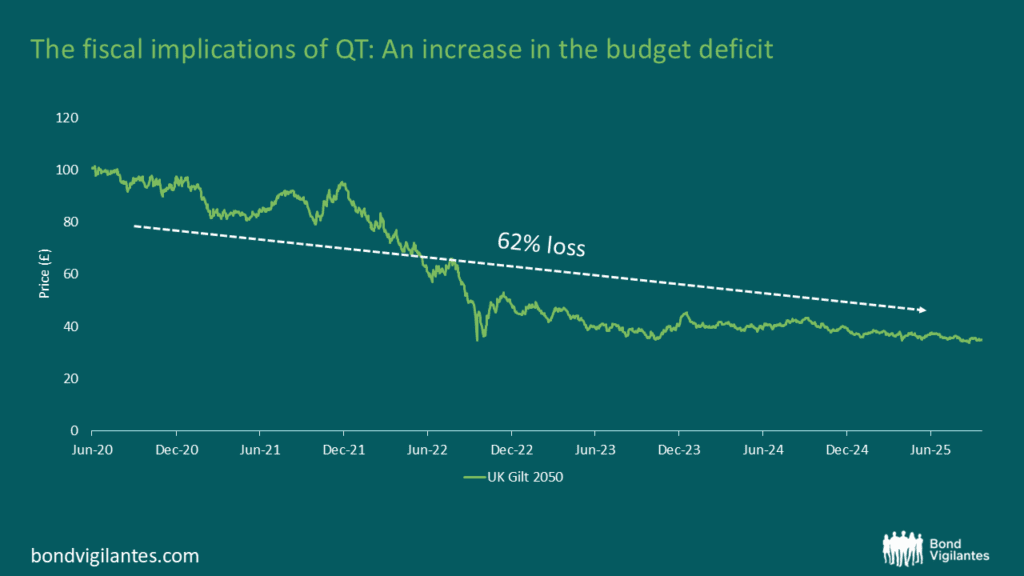

When the Bank of England sells a Gilt, it will make a profit or a loss. The chart below shows the price of a 30-year gilt from 2020 to the end of September 2025. A purchase during QE in 2020 at an average price of £96.2 ,combined with a sale now at a 2025 average price of £36.6, results in an overall loss of 62%. The Bank of England has this loss covered by the guarantee given by the UK government. Hence there is a transfer from the government to the Bank, resulting in the government deficit increasing. This transfer must be funded by, all else equal, tax rises or cuts in public spending. Therefore, the legacy of QT has fiscal implications.

Source: M&G, Bloomberg

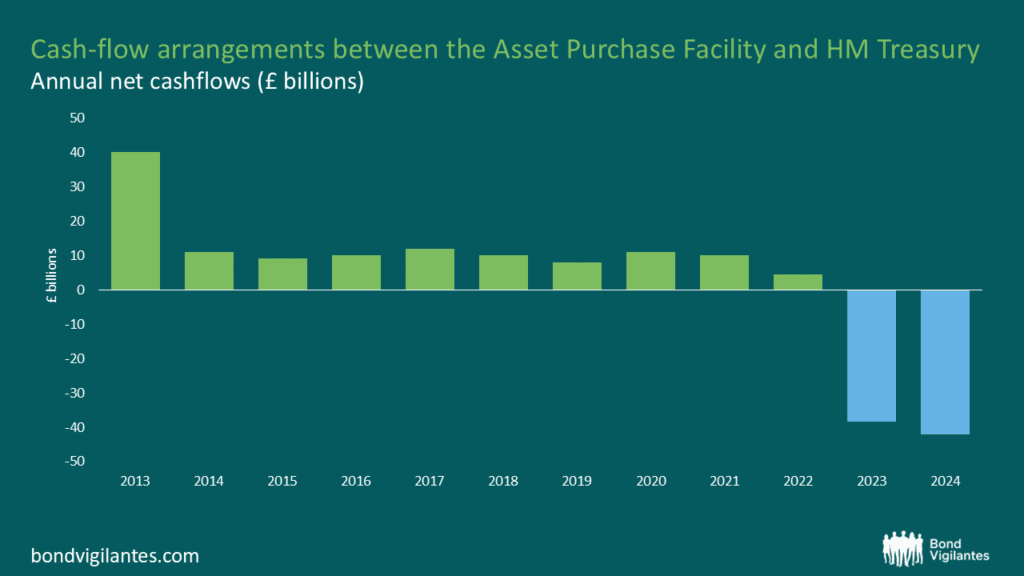

We can quantity the size of the fiscal boost and fiscal headwind in the chart below.

Sources: Bloomberg LLP for market rates as 31 December 2024. Bank of England calculations for data in relation to APF cash flows. NPV calculations based on end-December 2024 data.

To put these recent negative annual cashflows into perspective, in the 2024/25 financial year, the UK government raised around £840bn billion in tax receipts.

There is a lot of discussion about the fiscal position of the UK, with various factors coming to the fore: Brexit, COVID, election giveaways, and productivity growth. One that gets rarely mentioned is the fiscal pain of QT.

QE in the first phase made the government’s fiscal manoeuvrability… Quite Exceptional

While QT makes it… Quite Tough

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.