Corporate bond yield levels suggest M&A boom

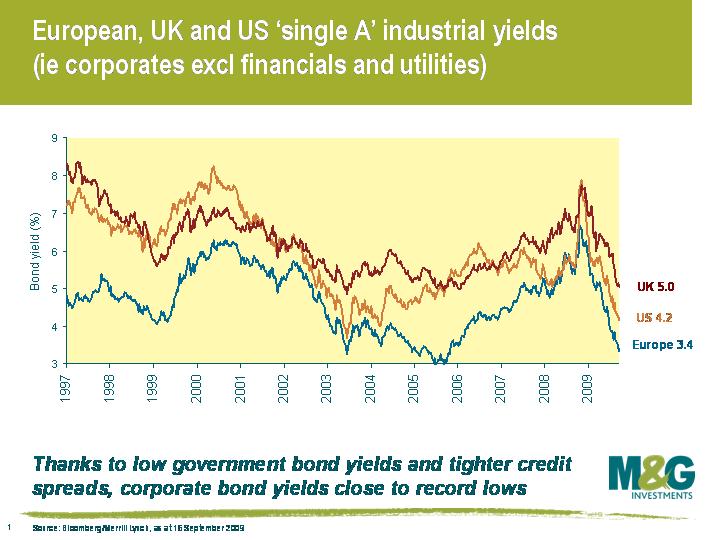

There has been a lot of talk about M&A activity, fuelled by Kraft’s attempt to buy Cadbury. Judging by where corporate bond yields are, this talk is entirely justified. The credit rally we’ve had, coupled with the fact that government bond yields are still very low historically, means that right now non-financial investment grade companies are able to borrow from debt markets at almost the cheapest levels ever. The attached chart shows the yield for the average single-A rated industrial company – citing specific examples of A rated companies,  McDonald’s can borrow in euros for five years at 3.6%pa, while GlaxoSmithKline can tap markets at about 3.5%pa for five year paper, and IBM at 3.3%pa. GlaxoSmithKline’s estimated P/E ratio is 12, which means that its equity earnings yield (ie the inverse of the P/E) is 8.3%, so it makes sense to lever up the balance sheet, either through share buybacks or takeovers.

McDonald’s can borrow in euros for five years at 3.6%pa, while GlaxoSmithKline can tap markets at about 3.5%pa for five year paper, and IBM at 3.3%pa. GlaxoSmithKline’s estimated P/E ratio is 12, which means that its equity earnings yield (ie the inverse of the P/E) is 8.3%, so it makes sense to lever up the balance sheet, either through share buybacks or takeovers.

Now it’s very important to stress that corporate bond yields around historical lows doesn’t mean that corporate bonds look expensive. As argued recently here, credit spreads are still at levels that you’d normally associate with a bad recession, and are at similar levels to the most distressed points seen in 2002. A bigger concern on our desk is that government bond yields are likely to rise (and portfolios are positioned accordingly), but that said, government bond yields do deserve to be lower than average – economic growth around the world is still very weak and will probably be anaemic for a while, deflation is still a major risk, and central banks’ policies should prevent government bond yields rising rapidly in the short to medium term.

Rising leverage has a longer term implication for credit markets, in that it is bad for credit quality. However while credit markets are ripe for an increase in leverage (at least in non-financial investment grade companies), it’ll probably take a while for the M&A boom to really kick in. A number of CEOs will have been scarred by being over-leveraged going into the downturn and won’t want a repeat. Plus a lot of the credit bubble of 2004-07 came from banks and private equity. Banks won’t be allowed to leverage up to anything like the same extent, and we’re quite a long way from another private equity/LBO boom (in fact the two groups are closely related – a friend in a relatively small private equity firm tells me that while banks have re-entered the market in the past three months, banks are having to club together on any deal over £20m, leverage multiples are almost half what they were a few years ago and the banks’ arrangement fees are double what they were in the boom times).

A final observation is that maybe the monetary transmission mechanism isn’t quite as broken as some think. As the global economy was heading for recession last year, central banks slashed interest rates and government bond yields tumbled. Central banks were desperate to contain the financial crisis within financial companies, and prevent the worst of the effects spilling over to non-financial companies. On this measure at least, the policy responses seem to have worked – many companies have gone from facing crippling refinancing costs at the end of last year, to enjoying the cheapest refinancing levels they’ve ever experienced. The leverage cycle normally follows the traditional business cycle, taking 8-10 years, but the authorities have been giving this cycle a serious dose of amphetamines.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

18 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox