UK inflation – upward pressure in the short term (though we’re still comfortable longer term)

Inflation rates, at least in the non-emerging markets, remain low. US core inflation (CPI less food and energy) was negative in January, the first month on month decline since December 1982. Preliminary German CPI in February was +0.3% year on year. Japan hasn’t recorded a positive year on year inflation rate since January 2009.

Things seem different in the UK. The annual UK inflation rate jumped to 3.5% in January, prompting Mervyn King to write yet another letter to Alistair Darling explaining why CPI had breached the upper limit of 3%, and prompting Darling to write yet another response.

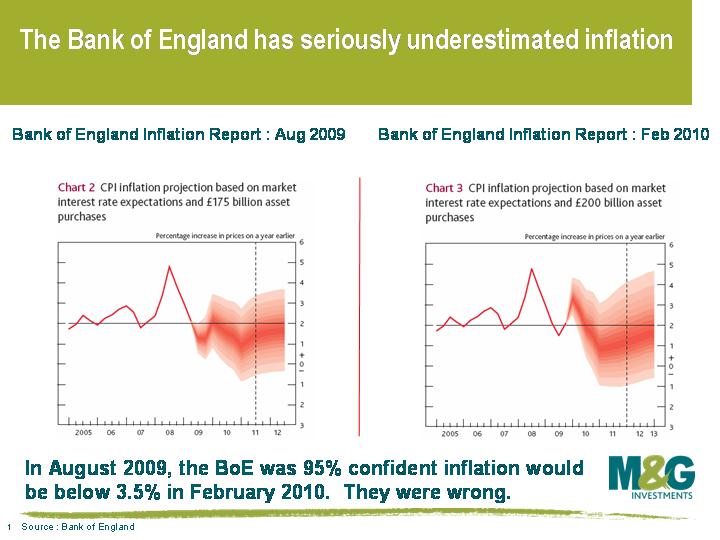

The BoE is confident inflation will fall, and has been busy telling people to relax, it’s just temporary, nothing to worry about, we said it would fall last time it was a bit high and we were right. But in August 2009, the BoE was about 95% confident that inflation would be below 3.5% in January 2010. They were wrong (see below). An ex-member of the MPC recently described the BoE’s fan charts to me as being “rivers of blood”, and the FT announced that it was not going to publish the fan charts any more. The market is getting worried about the accuracy of the BoE’s inflation forecasts.

Why is the UK inflation rate worryingly high and what’s likely to happen in future? ‘Base effects’ are usually given as the main reason inflation has picked up – inflation is a year on year number, the oil price was below $50 a barrel at the beginning of 2009, it’s now $80, and petrol prices have therefore risen. The good news is that base effects should prove temporary, unless the prices of things like oil continue rising rapidly or we see second round effects (eg higher wages). But is this the reason the BoE has significantly underestimated the UK inflation rate? I don’t think so – in August 2009, the Bank of England knew what had happened to energy prices in the first half of 2009 and would have factored this into their inflation projections. Since August, energy prices (which are admittedly a small part of the CPI basket) have barely moved, and besides, other countries don’t seem to have experienced base effects to anything like the same extent as the UK. So there’s clearly something else going on.

Government policies have definitely had an effect, particularly changes in VAT. The jump in UK CPI from 2.9% to 3.5% last month was partly due to the year on year numbers reflecting January’s increase in VAT from 15% to 17.5%. This effect will continue to be felt through to the end of this year when the VAT increase works its way out of the annual inflation numbers. We’ll probably therefore see elevated inflation levels until then, and again, this effect should be temporary. But, I think VAT is very likely to be increased to the EU average of 20% after the election, AND we may see a number of items that are not taxed (eg most food, children’s clothes, gambling, lottery tickets, museum tickets, antiques, water supplied to households, funeral services, incontinence products, freight, postage, newspapers, loans) start to get taxed. We may also see an increase in the tax rate on items that carry a reduced VAT rate (eg energy, some construction). Additional VAT increases this summer would put further upwards pressure on inflation, keeping inflation elevated until at least the second half of next year.

The third commonly cited reason for higher UK inflation is the weakness of sterling. This does not mean that sterling has been weak over the past twelve months – in the year to the end of January (the period covering the last annual CPI release), sterling actually appreciated about 10% against the US dollar and was up 4% on a trade weighted basis. What matters more, as explained in Mervyn King’s letter, is that we are still feeling the lagged effects of sterling weakness in 2007 and 2008. I think this lag effect is a very important point, and probably goes a long way to explaining why economists and probably the Bank of England themselves have underestimated inflation over the past year. Things like companies currency hedging, retailers setting prices months in advance and wage settlements being based on the previous year’s prices mean that there’s a significant lag effect between a currency rapidly depreciating (which increases the cost of imports) and these import price increases being passed onto consumers. Import price inflation peaked at more than 13% in December 2008, the highest rate since our data series began at the beginning of 1981. Michael Saunders of Citigroup has estimated that import prices lead consumer goods prices by a massive 30 months, and if this correlation between import prices and consumer good prices holds, then we could well see further upwards pressure on UK inflation through the remainder of this year and into the beginning of next year.

All these things suggest that UK inflation rate may be a lot stickier than the Bank of England expects over the next 12-18 months However, it’s important to stress that these effects should be temporary, and there are a lot of deflationary pressures going on right now which should prove longer term in nature.

We’ve talked about these longer term influences many times before. Money supply remains extremely weak – M4 broad money supply was flat month on month in January, and only +0.9% year on year versus +3.5% in July 2009 – just think what it would have been without any QE! (Note that this figure is using the BoE’s policy of stripping out the deposits of ‘intermediate other financial corporations’, which excludes things like counterparties and SPVs). Spare capacity is still huge, and very importantly, the enormous trimming in the budget deficit and cut in government spending that is absolutely necessary and will definitely happen will have a major negative impact on growth, meaning that spare capacity is here to stay. Bank lending remains subdued, as evidenced by a dropping away of mortgage approvals in recent months from already pretty feeble levels – the authorities’ continued failure to generate meaningful demand for or supply of credit should keep inflation suppressed.

I wouldn’t put it quite as strongly as the MPC’s Adam Posen, who last month said that “any of you betting on high inflation in major economies, including the UK, will lose money” – there are certainly upside risks (eg sterling collapse, underestimation of the inflationary effects of QE) – but on balance there’s little to suggest that we’re going to have inflationary pressure beyond the next 18 months.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

18 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox