An emerging market country issues lots of century bonds – reason to worry?

Last week BBB rated Mexico issued a 100 year bond denominated in US dollars. It was originally supposed to be a $500m issue, but as is typical in any EM bond issue at the moment, the book soared to almost $3bn so the government decided to take advantage and make it a $1bn issue. It was issued at a price of 94.3, which meant it had a yield to maturity of 6.1%, or 2.35% more than a 30 year US Treasury. The bond’s price has since soared, and is now at a price of 101 (yield of 5.7%, excess yield over 30 year US Treasuries of 1.8%).

A ‘century bond’ is a good headline grabber, and most people’s instinct is to question why someone would want to lend money to a country whose credit rating is only 2 notches above junk status in the knowledge that you won’t get your principal back until long after almost everyone currently on the planet is dead. However, once you look at the bond maths, it’s not really all that incredible. The time value of money means that $100 in today’s money is only worth $0.3 in 100 years (assuming an interest rate of 6% that’s payable semiannually). In other words, 99.7% of the cash flows from this Mexico bond will come from interest, rather than the final principal. The bond will actually behave very much like the 2040 Mexican bond that’s been around since January 2008 – the 2040 bond has a duration of 14.8 years versus 18.1 years for the century bond, so there’s little difference in risk. (As a comparison, the UK 1.25% 2055 Index-linked gilt has a duration of 35.1 years)

So the existence of a 100 year senior bond isn’t a worry per se – indeed, it makes sense for a borrower to take advantage of low US Treasury yields and (at least in EM) historically tight credit spreads to lengthen out its maturity profile. Such behaviour reduces short term funding pressures, and ultimately improves credit quality. And the existence of a very long maturity bond is hardly new; if you consider all the subordinated financial perpetual bonds that were issued in the noughties, we’ve seen far worse.

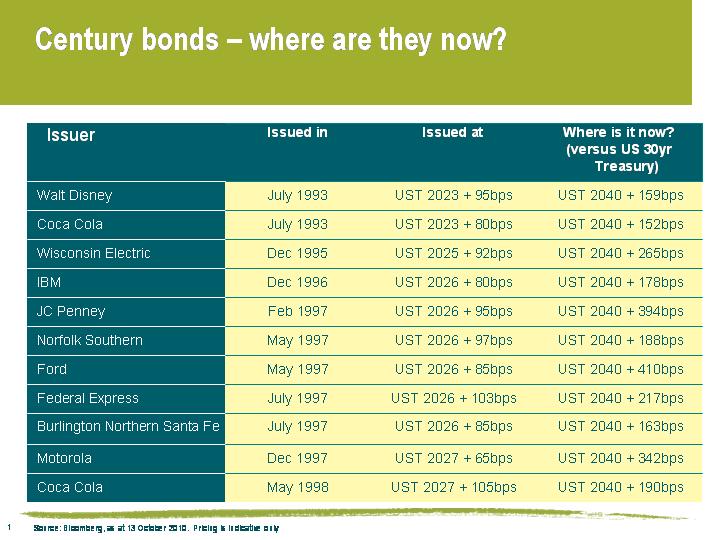

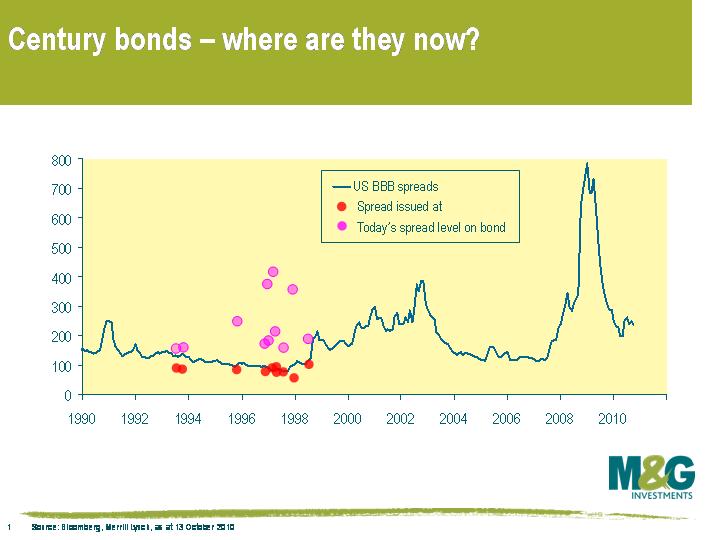

The worrying sign is simply that if a borrower thinks that it’s a fantastic idea to do something relatively unusual because it believes that the terms to do so are very attractive, then it’s unlikely to be such a great deal for the lender. This table shows what happened to the original century bonds that were issued by US corporates in the 1990s (see chart, and note that this is just a selection of the larger issues – century bond issuance peaked at 56 in 1996-97, with very few since)

This chart is another way of demonstrating that the surge in century bond issuance in 1996-97 occurred at a time when credit spreads reached exceptionally tight levels, and credit spreads in all companies I’ve listed above are now wider (in line with the broader market), with some substantially wider. The red circles are the spreads at the time of each of the issues, and the pink circles show where the spreads on these bonds are currently.

Prior to last week, China and the Philippines were the only EM sovereigns to have issued century bonds. I wouldn’t be surprised if Mexico’s successful deal spurs a number of governments and companies into following Mexico’s example. But if the experience of the mid 1990s is anything to go by, then let that be a warning – the Philippines’ century bond was issued in June 1997, and July 1997 was not a nice time for Asian economies to put it mildly.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

18 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox