Happy Hogmanay – would an independent Scotland still be rated AAA? And might the rest of the UK get downgraded too?

Happy Hogmanay – an independent Scotland looks AAA on the back of an envelope (as long as it gets all of the oil and none of the banks!), but would probably get rated lower. UK to get downgraded on uncertainty?

We’ve obviously been thinking a lot about the break-ups of currency areas lately, and it got us thinking about an Optimum Currency Area closer to home. What would happen if the UK broke up? We did talk about what might happen to the gilt market if Scotland left the Union back in 2007 (see blog here), but political events this year have made it less of a theoretical question, and one that outgoing cabinet secretary Sir Gus O’Donnell asked at the end of December.

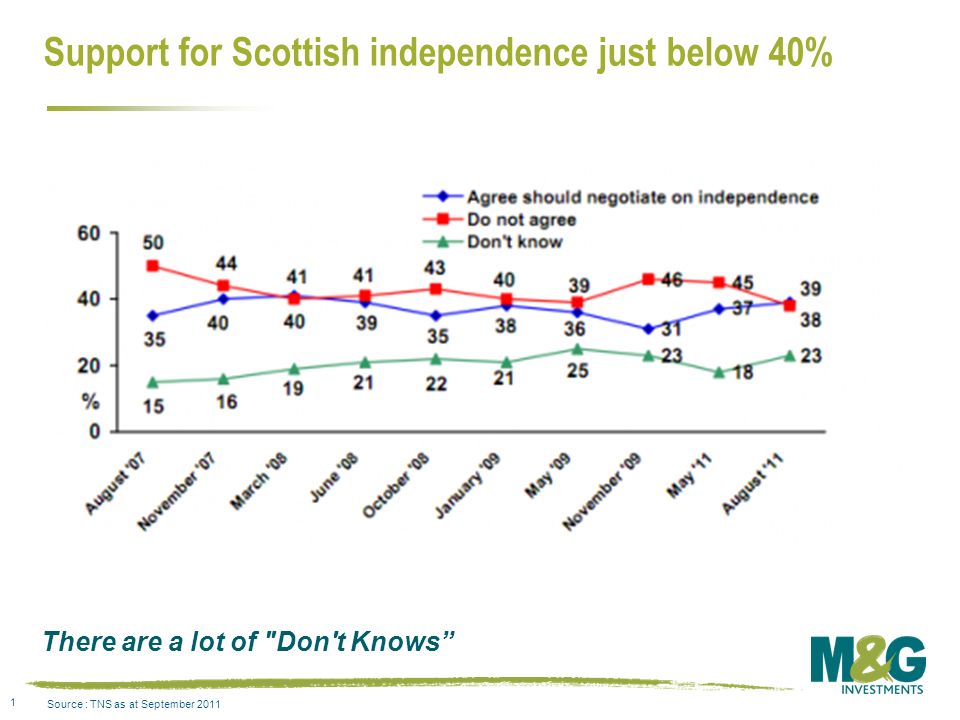

First of all, is it likely? During 2011, the Scottish National Party gained a majority in the devolved Scottish Parliament. It is now able to call for a referendum on the issue of full Scottish independence. It will do this sometime in 2014 or 2015, in the second half of the Parliament, and can also determine the question to be asked (worth a handful of percentage points to the question setters’ cause). If there is a “Yes to independence” vote, Scottish MSPs will need to pass a bill calling on the UK Parliament to negotiate terms for a break-up of the Union. That’s where the fun starts, as we’ll see. But will it happen? Back in October a YouGov poll put the “Yes” vote at 34%, with a decent number of “don’t knows”. But since the Eurozone problems began to accelerate, and UK growth prospects also slowed, it looks as if more recent polls have the “Yes” vote at around 28% (BBC November poll), with 17% “Don’t know”. The TNS opinion poll in the chart below however shows a much higher level of support for independence. The large differences in the outcomes of different polls reflects the wording of the question posed, and whether there is a simple “yes/no” or whether a third option for increased devolution within the UK is offered.

The SNP independence cause may have been damaged somewhat by developments since Alex Salmond’s 2006 “arc of prosperity” comments in which he favourably compared Scotland to Ireland and Iceland (now both with economies on life support – the “arc of insolvency” as Labour dubbed it) and also by their commitment to adopt the euro, at a time where peripheral economies which did adopt the euro are facing deflation, social unrest and default.

But let’s assume that the “Yes” vote returns to its October levels, and that the “Don’t knows” are converted to “Yes”, so that the Scottish people vote for independence in 2014. What happens to the bond market? Is the UK ex Scotland still AAA, and what credit rating would Scotland have? AAA like Norway, or lower? Maybe a good starting point would be to share out the UK’s national debt in terms of population. The UK population is 61.8 million, of which 5.2 million people live in Scotland. So Scotland becomes liable for 8.4% of the national debt, which equates to about £80 billion of the £940 billion debt.

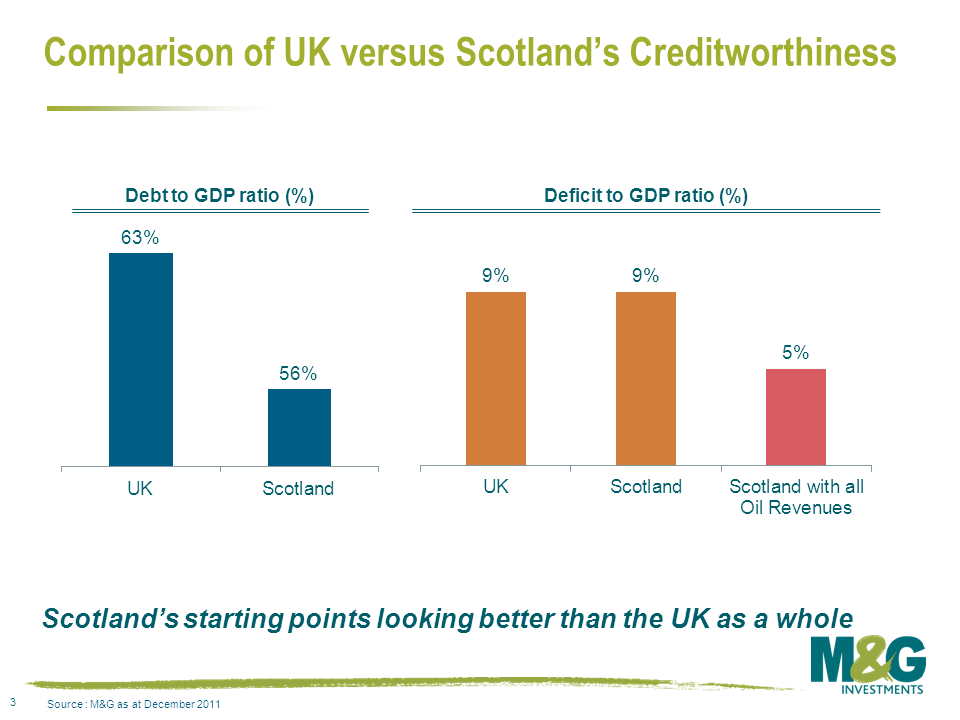

To be a AAA rated economy, you would hope to have a debt/GDP ratio of about 60% or lower (although there are now AAA countries with ratios heading to 100%), and that your interest costs would run at under 12% of your state revenues. Scotland’s GDP in 2009 was £143 billion (including all oil and gas produced in its waters), so its debt/GDP ratio would be 56% – respectable. The average interest rate on the existing stock of national debt is about 4%, so Scotland’s debt servicing costs would be £3.2 billion per year. Scotland’s revenues from taxes and duties in 2009-10 were £41.2 billion, so its interest payments to revenue metric would be just 8%.

Ah. But that’s just the “ordinary” debt. What if we add in the government money committed to “Financial Interventions“, which the headline numbers exclude nowadays. These financial interventions include the debts of the nationalised/part-nationalised banks (Northern Rock, Bradford & Bingley, Lloyds and RBS), and also money used in the bailouts of London Scottish Bank, and the Dunfermline Building Society, amongst others. The assumption of the debts of these nationalised/semi-nationalised banks onto the balance sheet of the UK takes the national debt from below £1 trillion to over £2.25 trillion. Because the government expects to sell these stakes back to the market, these are regarded as temporary liabilities and excluded from the headline numbers – the numbers also ignore that these debt liabilities fund assets so it’s not the black hole it might seem to be. But if you were a bad tempered English MP negotiating the break-up of the Union, might you highlight that much of the banking sector interventions directly involve Scottish banks (mainly RBS, HBOS) and perhaps suggest that as well as 8.4% of the gilt market liabilities, independent Scotland might like to take its banks back too? The assets of Royal Bank of Scotland and (Halifax) Bank of Scotland alone dwarf the size of the Scottish economy (on the back of an envelope they amount to 1400% of Scottish GDP; Iceland’s bank assets peaked at 1100% of GDP in 2008). Countries with relatively low public debt to GDP ratios still get into difficulty because of their private sector debt – at times of trouble, private debt often becomes public debt (the process where profits are privatised, and losses socialised).

Let’s assume that Scotland doesn’t have to support the banks. The bigger problem revolves around the sustainability of Scotland’s strong credit position. The starting point for debt/GDP and revenues versus interest costs look good for Scotland on a headline basis (i.e. forgetting about the banks, if we’re allowed to!); but is that relatively low debt burden maintainable? Oxford Economics produced a paper suggesting that of all the regions in the UK, Scotland made the biggest net negative contribution to the UK public finances. In 2004/05 Scottish revenues were about £35 billion, compared with government expenditures of £45 billion. In other words there was a net transfer of about £10 billion from 3 English regions of the UK (Greater London, the South East and Eastern regions – all other regions were net negative too). So Scotland would need to borrow this, plus its share of gilt interest at £3.2 billion each year to maintain a balanced budget. So £13.2 billion of deficit, compared with GDP of £143 billion is about 9% – about the same as the UK is running right now, but way above a sustainable number (for example the uniformly ignored Maastricht limit for Eurozone members is at 3%).

Now the elephant in the room. Oil. If Scotland were to receive its share of the revenues (North Sea Corporation Tax and Petroleum Revenue Tax) from the remaining North Sea oil, its position improves dramatically. In 2021/12 these totalled £6.5 billion, of which geographically Scotland is entitled to 91%, so £5.9 billion – although this is a volatile number which moves with the oil price. So on an annual basis the budget deficit falls from £13.2 billion to £7.3 billion – a deficit of 5%. Nice. On a present value basis, assuming these levels of revenue forever and a discount rate of 4% (to equate with its debt service costs) the oil revenues are worth £163 billion; but North Sea oil revenues are likely to fall aggressively from here – 1999 was probably “peak oil” for the North Sea, and by 2020, production will be a third of 1999 levels. So again, if I’m rating Scotland as a stand-alone entity, I worry what will happen going forwards. If you sold future revenues today you could wipe out Scotland’s national debts – and even invest in a Sovereign Wealth Fund (SWF) like the Norwegians with the change (£80 billion or so)!

May I take a moment to rant about the lack of a UK SWF? In real terms the UK government has taken £270 billion out of the North Sea in tax revenues. Did we save it, like the Norwegian Statens pensjonsfond, now worth around £330 billion? Nope, after millions of years spent turning bracken into oil, we gave it away in a 20 year period to a population who just happened to be alive under a particular government’s time in office and got a windfall gain which they used to buy avocado coloured plastic bathroom suites, now doomed to eternity in landfill across the nation. Bah.

What else would a rating agency consider when determining Scotland’s credit rating? The US gets a massive boost to its rating due to its status as a global reserve currency, Japan has so much domestic saving that it can run a debt/GDP ratio of 200% and still be Aa3 rated, and the UK survives as AAA in part due to it being able to print its own currency. Additionally, ratings agencies favour big, systemic nations over smaller ones where there is an implied higher risk factor (rightly or wrongly) and given the experience of Iceland and Ireland which both held AAA ratings perhaps the agencies would err on the side of a lower rating. The currency point is interesting – the SNP position was to adopt the euro (a difficult one to get through the voters today I would guess), but Scotland could keep the pound (either officially with access to the Bank of England, or unofficially – Zimbabwe uses the US dollar without being part of the Federal reserve system), or print its own currency (pegged to the Euro, pound, price of oil, nothing).

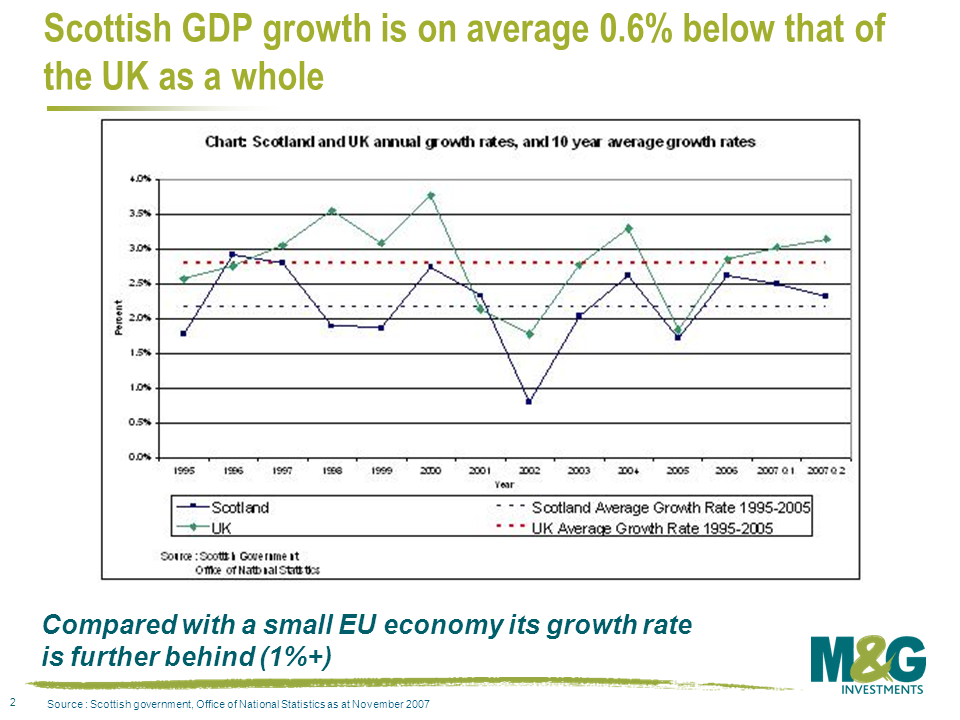

Also very important when considering debt servicing ability is the growth rate of the economy. Scotland performs relatively poorly on this measure (although one argument from those who want independence is that only when Scotland is separated from the UK will it be in charge of its own economic future, and its underlying growth rate can improve). Currently Scotland’s average GDP growth rate is 0.6% per year behind the UK as a whole, and around 1% behind that of the other small European economies. The public sector represents 24% of Scottish employment – higher than in the rest of the UK, although it is falling as part of the recent austerity programmes. As well as being a drag on economic productivity, a disproportionate public sector also means a higher level of unfunded pension liabilities – a contingent liability, like the probable losses involved in the bank bailouts.

So my guess is that a rating agency would not give Scotland a AAA rating, and that the market would trade any bonds it issued at a wider yield than the UK which still benefits from some reserve currency status. The next question we want to answer is how would a break-up impact the gilt market? Would I be given £8 of Scottish gilts and £92 of UK gilts for every £100 of gilts I own now? Can “they” do that to me? It would count as an event of default for the UK in CDS markets, and almost certainly also for the rating agencies, unless this was a voluntary exchange. Logistically nightmarish, so our UK sovereign credit analyst Mark Robinson suggests that the UK would keep all of the gilt liabilities, and Scotland and the UK would have a bilateral loan for an equivalent amount (the UK has a bilateral loan for about £7 billion to Ireland for example, albeit in very different circumstances). I doubt that the UK’s credit rating would change as a result of any fundamental economics of Scottish independence – but international investors might worry about the instability, real or imagined, of the Union breaking up, so a downgrade for the UK is not out of the question. Mike Riddell here has been doing some digging on what happened to assets and liabilities when states and unions dissolved (e.g. Russia assumed all of the USSR’s debts, Yugoslavia’s carve up was much more complicated) – he’ll post up some thoughts some time soon I hope.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

18 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox