Nominal GDP targeting for the UK, coming sometime, maybe?

This speech by Mark Carney, incoming Bank of England Governor, to the CFA Institute in Toronto, is potentially very important for UK monetary policy. He appears to suggest that targeting a level of Nominal GDP (NGDP) can be more powerful than an inflation target. Importantly he also emphasises the “history dependence” of such a policy regime, and that “bygones are not bygones”. Central bankers would be compelled to make up for past misses. Holes in growth, caused by recessions and slowdowns, need to be filled in.

George Osborne, UK Chancellor, has appeared to be warm to a discussion about a change in the UK’s monetary policy regime (and he appointed Carney to the Bank). But what would it mean in practice? Nominal GDP targeting means that monetary policy would aim to hit a combination of growth and inflation over time consistent with its trend. In the case of the UK this might be 2.5% real growth and 2% inflation, so 4.5%. But the wonderful thing about nominal GDP targets is that you don’t really care about the mix, so 4.5% inflation and 0% real growth is as good as 4.5% real growth and 0% inflation. Or at an extreme, a fall in real GDP of 10%, and inflation at 14.5%. I think that many of us would regard this indifference between growth (“good”) and inflation (“bad”) as strange. Is this an example of a policy that turns failure (having persistently higher than target inflation rates) into a triumph? Not even, I’m afraid as we haven’t achieved a 4.5% nominal GDP rate in the UK in recent times as real growth has hovered around zero.

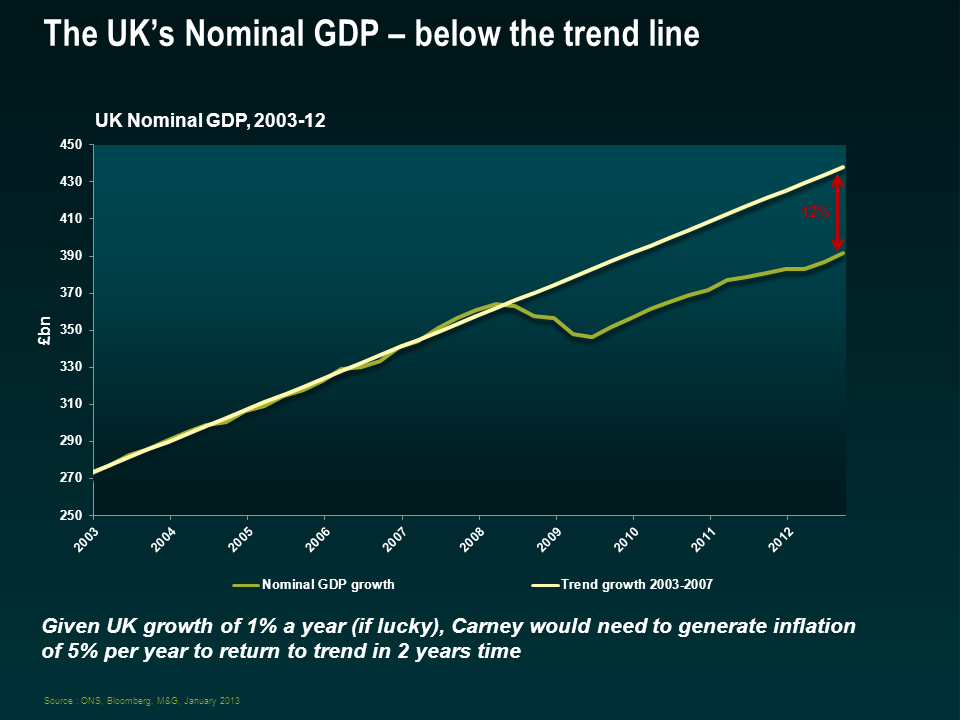

I have some other issues about the proposed policy too. The estimation of the trend itself becomes very important. On this chart I show, in green, the level of UK nominal GDP. If we draw a trend line, using the period from 2003 to 2007 and project it forward, it appears that the level of UK growth is still significantly below trend. On my calculations it’s around 12%, but I’ve heard estimates (including from within the Bank) of 15-16% below trend too. You can see that given how weak real growth is in the UK (we may have gone back into recession), we would need to generate a significant amount of inflation to return to the trend level within the next couple of years. After all, the Bank would be “compelled to make up for past misses”.

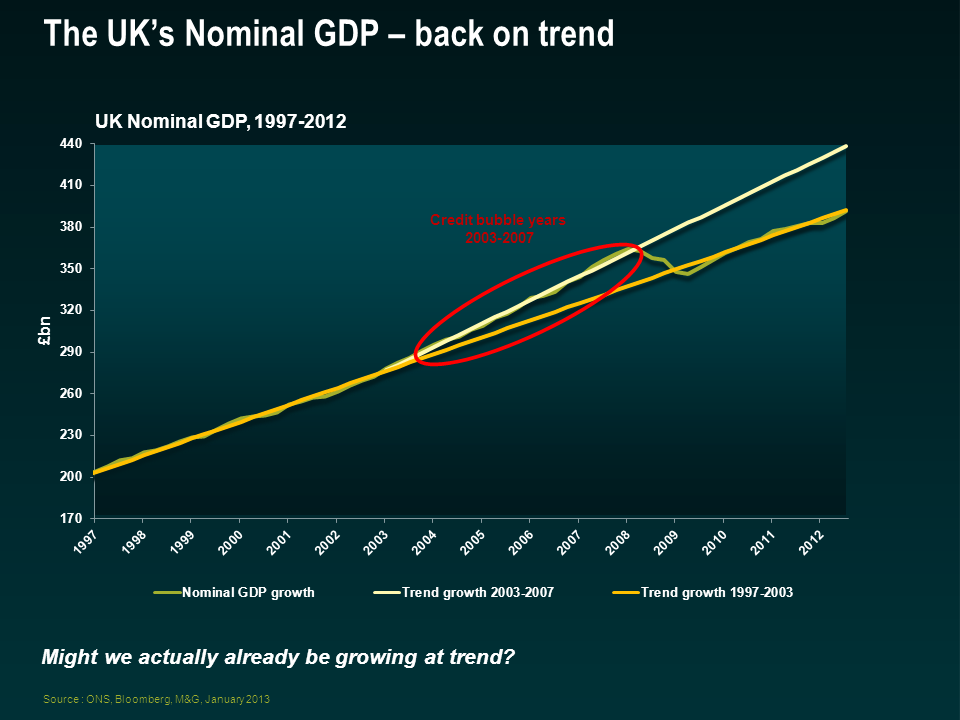

But what if that trend rate of growth was too high? 2003 to 2007 was in the white heat of the credit bubble, and growth came from all directions, consumer spending and government spending. It seems very plausible that we were growing above our potential at the time, thanks to cheap money and leverage. If we show the same chart with a trend line from the period before credit exploded, say 1997 to 2003, we get a very different gap. In fact the yellow line here shows that the current level of Nominal GDP is bang on where we might expect it be. Perhaps this explains why the UK’s employment situation has been relatively strong in the period since the credit crisis, and perhaps it explains why inflation has been so sticky to the upside – maybe we are operating around full capacity already?

There are other objections of course – inflation data are never revised, whereas GDP numbers are, sometimes drastically. So central bankers could be aiming at a historical number that might change significantly (most economists expect UK GDP to be revised higher for the period since the credit crisis). But perhaps the greatest criticisms are reserved for the damage this might do to monetary policy credibility – does not caring about the mix of inflation and growth increase the risks of inflation drifting further away from 2%? And some have suggested that countries that have followed a NGDP regime have experienced higher volatility of both output and inflation compared to those that target inflation alone.

So on the face of it, I’m not a fan. But I am a pragmatist, and the debt to GDP ratios that we have now (or are baked in the cake for the future thanks to demographic trends) can only be dealt with by either above trend growth (are we going to see 4% real growth in the UK for any sustained period?), or higher inflation. No central banker will ever tell you that this type of regime change is taking place to erode the national debt. But if growth continues to stagnate, and politicians remain reluctant to take difficult decisions on pensions, tax rates and benefits, inflating the debt away looks to be the only option. Outright government bond defaults are unnecessary in countries with their own currencies – but subtler defaults will happen – against populations as we find that the promises made to us about our old age or child benefit no longer apply, and with inflation reducing the real liabilities of the government. This is Central Bank Regime Change, and you won’t like it.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

18 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox