Irish eyes are crying when they look at the economy

With St. Patrick’s Day around the corner, we thought there would be no better time to do an economic update on Ireland.

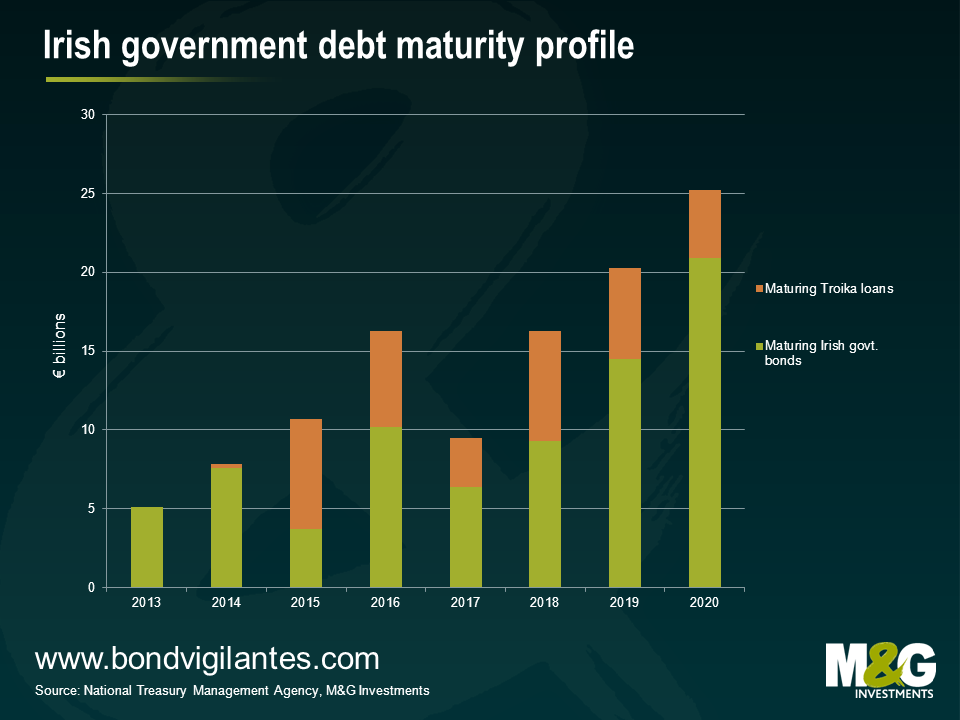

In November 2010, Ireland found itself bankrupt. Dublin’s promise to keep bank creditors whole resulted in a massive increase in its debt obligations – too big for the government to remain solvent; especially after yields on 8 year government bonds rose to over 7% (they would later increase to over 15%). In desperation, Ireland turned to the European Commission, the European Union and the International Monetary Fund (the so-called “Troika”) for assistance.

After lengthy negotiations, Ireland received a €67.5bn international bail-out from the Troika, after yields on Irish government bonds rose to record levels. In return, the Irish government agreed to downsize and reorganise the banking sector so that it became proportionate to the size of the economy. The government also agreed to significant fiscal and structural reform, including austerity measures of €15bn over four years. This adjustment was to be made up of €10 billion in expenditure savings and €5 billion in taxes. This three year assistance programme is due to conclude at the end of 2013.

It was hoped that by implementing these reforms that Ireland would be able to return to the international capital markets and that investors would again lend to the Irish government. And that is indeed what has happened. As recently as January, Ireland issued €2.5bn of bonds maturing in 2017 at 3.32%. There are now hopes to issue a benchmark 10-year bond and possibly a linker in 2013.

Ireland cannot use the billions of euros it received from the Troika to embark on stimulatory policies for the economy. The money loaned to Ireland is sent to Dublin by the Troika, pumped into the Irish banks, and then channelled to Irish bank bondholders. The man on the street doesn’t see a cent. It was hoped that the bailout would benefit the Irish taxpayer by preventing even harsher austerity.

With that in mind, how has the real economy performed?

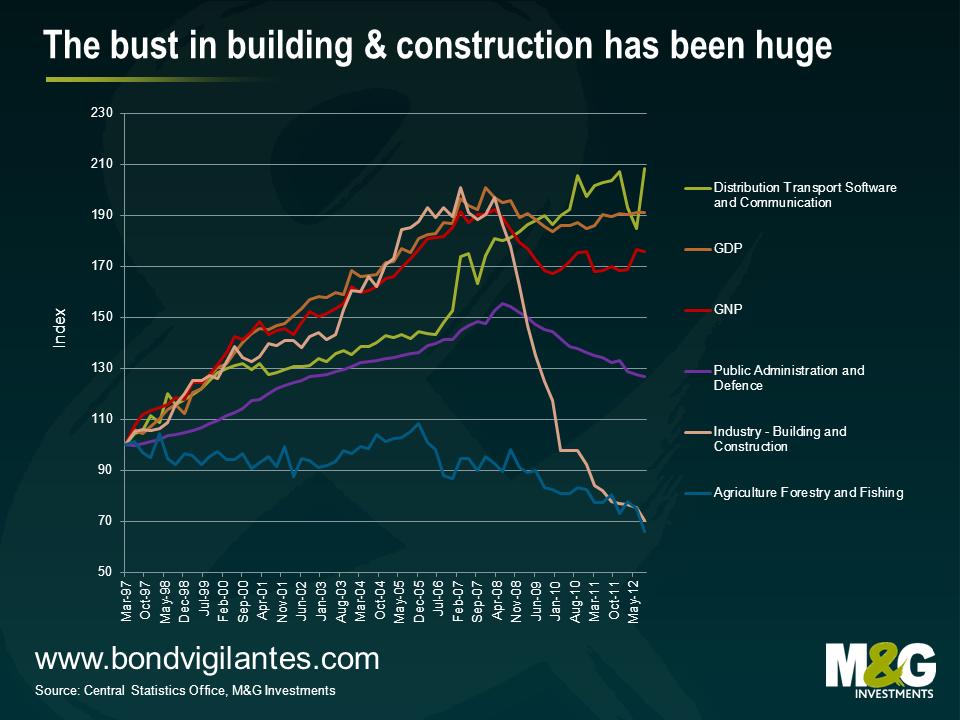

As would be expected, the evidence suggests a weak recovery at best. Ireland expanded at a pace of 0.8% over the year to September 2012 despite an environment of high unemployment and fiscal austerity. Looking at the sectors that contribute to GDP, we can see some improvement in the combined distribution, transport, software and communication sectors. At around 25% of the economy the Irish government is hoping that an increase in demand for Irish goods, particularly within the pharmaceuticals and information technology sectors, will support growth over the medium term. A weaker euro will help, particularly against the US dollar (the US is a big market for Irish exports – around 24%), but it is not weak enough.

Given that many of Ireland’s major industries – like pharmaceuticals – are highly capital-intensive they tend to employ few people. Additionally, the capital used in these industries is largely owned by foreigners and hence the benefits of profits are repatriated out of Ireland. Thus gross national product, which deducts income paid to foreigners, is a more relevant gauge of how the economy is performing. And on this measure, the Irish economy isn’t too cash hot, remaining significantly below the pre-crisis trend.

The above chart is a good illustration of the housing and construction boom that occurred in the run-up to the financial crisis of 2008. Housing and construction peaked in March 2007 and has since contracted by 65% in real terms. Despite only being around 7.5% of the economy at its peak in 2006, the boom and subsequent bust in this sector highlights the significant multiplier effects that the housing market can have on an economy (and is something we have highlighted here).

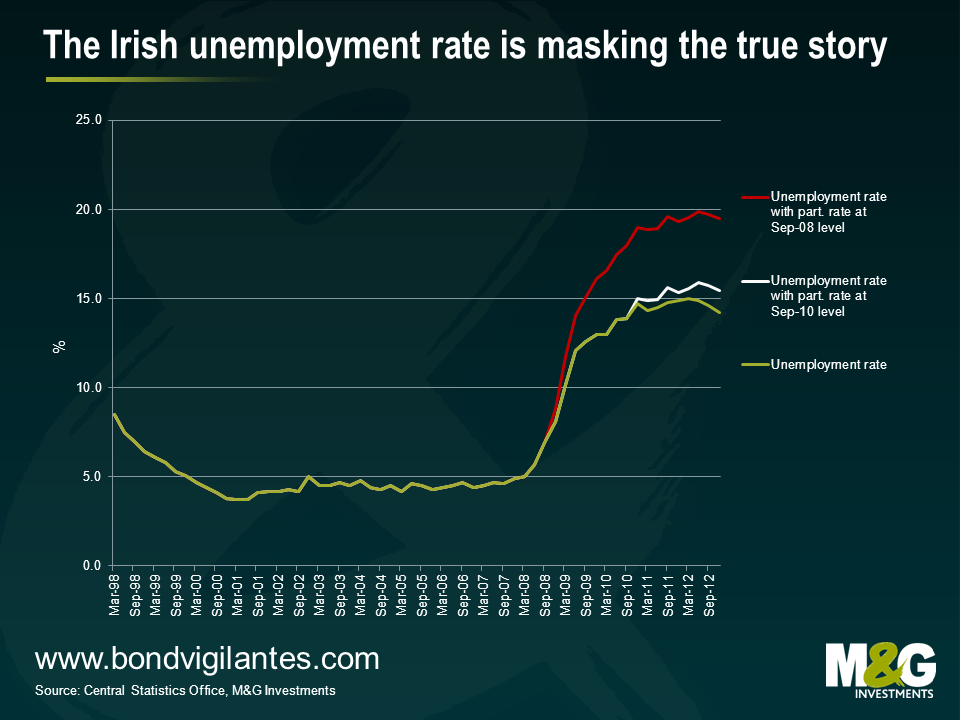

Turning to the labour market, it is true that the deterioration in labour market has stopped over the past year. The unemployment rate peaked at 15.0% and has now fallen to 14.2%. Many are pointing to the improvement in the labour market as a sign that the Irish economy is healing. We are less sure.

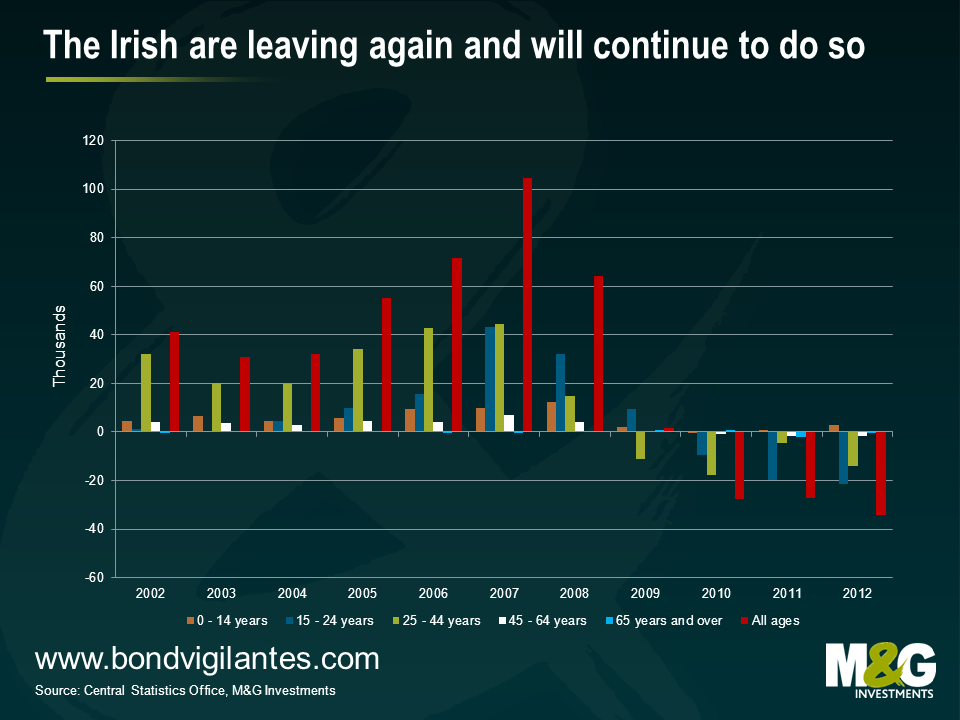

Holding the participation rate steady at September 2008 levels, the unemployment rate is closer to 19.5%, a full 5.3% higher than the current unemployment number of 14.2% suggests. This equates to around 140 thousand people. Where have they gone?

Net migration figures show that between the years of 2009-2012, a total of 87 thousand people left Ireland and predominantly between the ages of 15-44. Net migration, a declining participation rate and an increase in discouraged workers goes some way to explain the reduction in the Irish unemployment rate. The labour market isn’t healing; in fact the number of employed people in Ireland has fallen from a peak of 2.16 million in the third quarter of 2007 to 1.85 million at the end of 2012.

We have heard much about the internal devaluation going on in Ireland, which has been seen as a sign that Ireland is becoming more competitive in the global economy. True, unit labour costs (ULC) fell by 16% from the peak in Q4 2008 to Q3 2012. But this is misleading of the more recent trend. From Q1 2010 to Q3 2012, unit labour costs fell by only 3.4% and from Q1 2011 to Q3 2012 unit labour costs have actually been flat. This very slow reduction in unit labour costs in recent years suggests that it will be a decade or more before it is competitive. Ireland is seen as a nation with one of the more flexible labour markets in the Eurozone. What hope is there for Italy, Greece, Spain or Portugal with their relatively inflexible labour markets?

We fear for the Irish economy. What is required is stimulus, not austerity. Without some form of stimulus package, the Irish economy will experience sub-trend growth for the foreseeable future (in contradiction to the IMF’s forecasts – see here). A good place to start would be to use using some of the proceeds from borrowing at record low interest rates in the capital markets to stimulate the economy. The €2.25bn stimulus package was a good start last July but much, much more is needed. For example, how about a helicopter drop of cash into the economy Bernanke style? Give the estimated 4.5 million inhabitants of Ireland €200 each? It would only cost €900 million. Cut income tax. Encourage investment and lending. Build infrastructure. Create jobs. Reverse austerity.

Or how about using the money raised to embark on a programme of debt forgiveness in order to provide homeowner relief. Find a way for homeowners to take advantage of low interest rates and refinance despite having limited/negative equity in their homes. Allow refinancing to occur on a mass scale.

I know, I know. What about the loss of faith in Ireland’s credit rating? What about the spike in government bond yields? Well hopefully the stimulus package would work. Besides, ECB President Mario Draghi will do “whatever it takes”. And we believe him when he said “And believe me, it will be enough”.

If Ireland continues to tie its flag to the austerity mast, it is difficult to see a time in the next decade when the economy will cause Irish eyes to smile again.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

18 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox