Australian sport as a lead indicator for the housing market

Being an Australian sporting fan hasn’t been easy during my time at M&G over the past five years. The Olympics, rugby, cycling, cricket, tennis… Britain’s golden-age of sport has coincided perfectly with the decline in Australia’s sporting prowess. On top of this, I had the misfortune of seeing my premier league team get relegated last season (though there are definite green shoots of recovery emerging for QPR) and I am about as excited about the upcoming Ashes series as someone who has just been told that they need root canal surgery.

It has now got to the stage that my British colleagues – with memories of their national sporting teams’ performances during the 90s in the back of their minds – have taken pity on me, stating that it’s all cyclical. It’s enough to make you cry into a snakebite down at the Walkie (there’s only one left in London!).

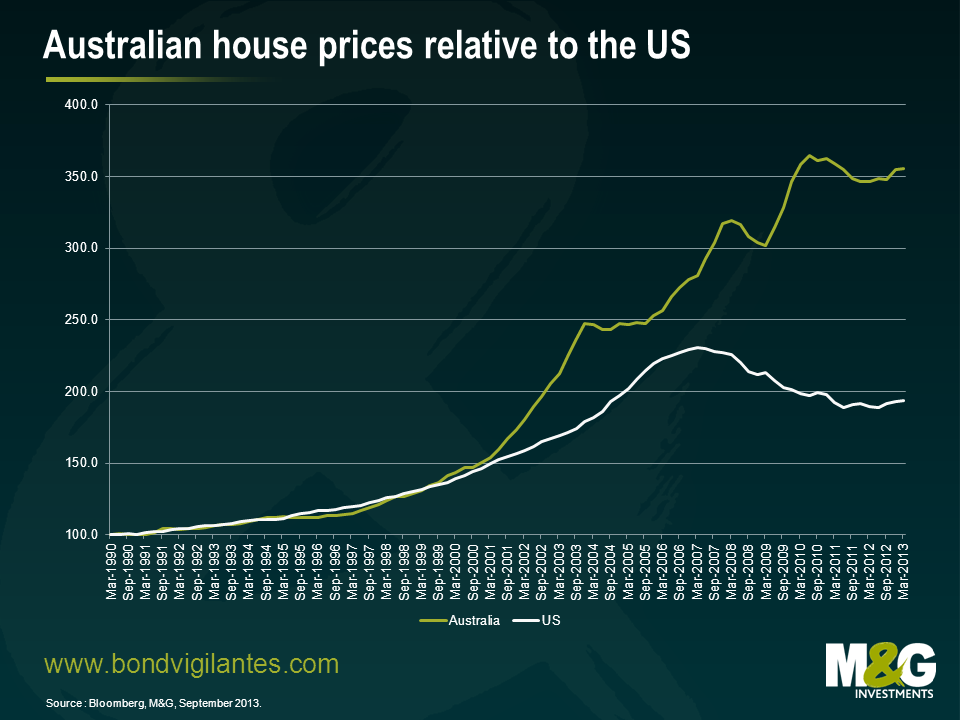

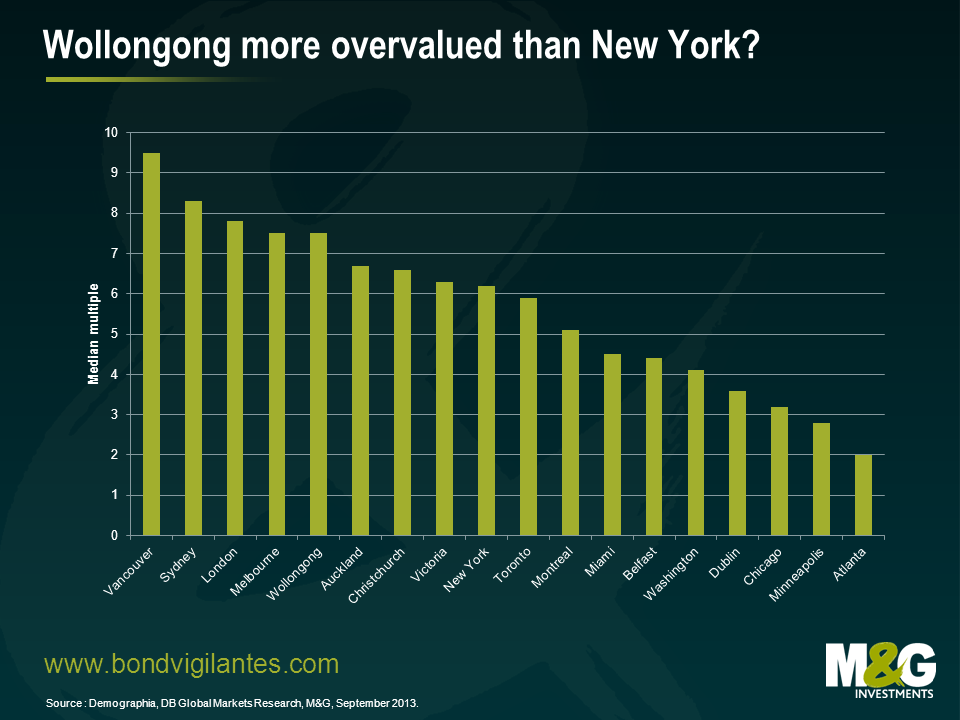

One thing that hasn’t been cyclical is the Australian housing market. House prices seem to go only one way, and that’s to the moon. Australians haven’t had much to talk about on the sporting front in recent years, so most of the chat at BBQs has turned to properties (“How many do you own?”) and prices (“Get your feet on the housing ladder”). The increase in Australian house prices far exceeds the land of sub-prime loans (the US) and goes some way to explain why Sydney, Melbourne and Wollongong are more expensive on a median multiple basis than New York, Miami and Washington.

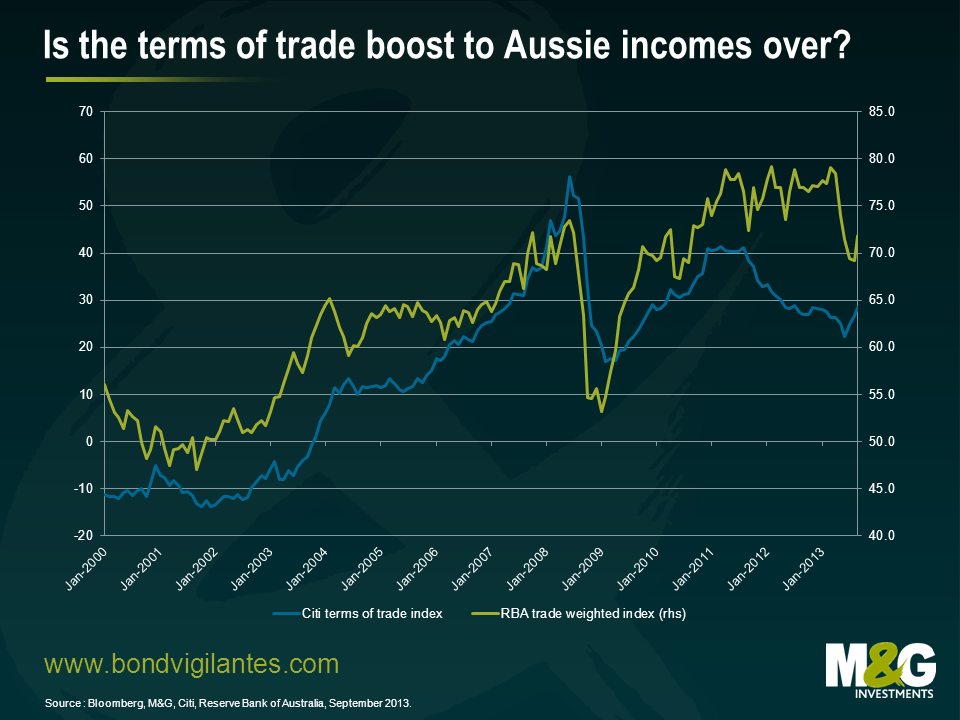

Twenty-one years of sustained economic growth, low unemployment and the boost to incomes that has come from a record increase in Australia’s trade, have lulled most of the population into a false sense of security that house prices will never go down. There is a well-known rule in Australia for property investing – prices double every 7-10 years. Absolute madness. Throw into this economic bonfire the most favourable tax treatment of property investments in the world and record low interest rates and it’s easy to see why there is a clamour to own bricks and mortar. Not only as a source of shelter but also as a retirement policy. The blinkers have been well and truly fixed to the Aussie home buyer.

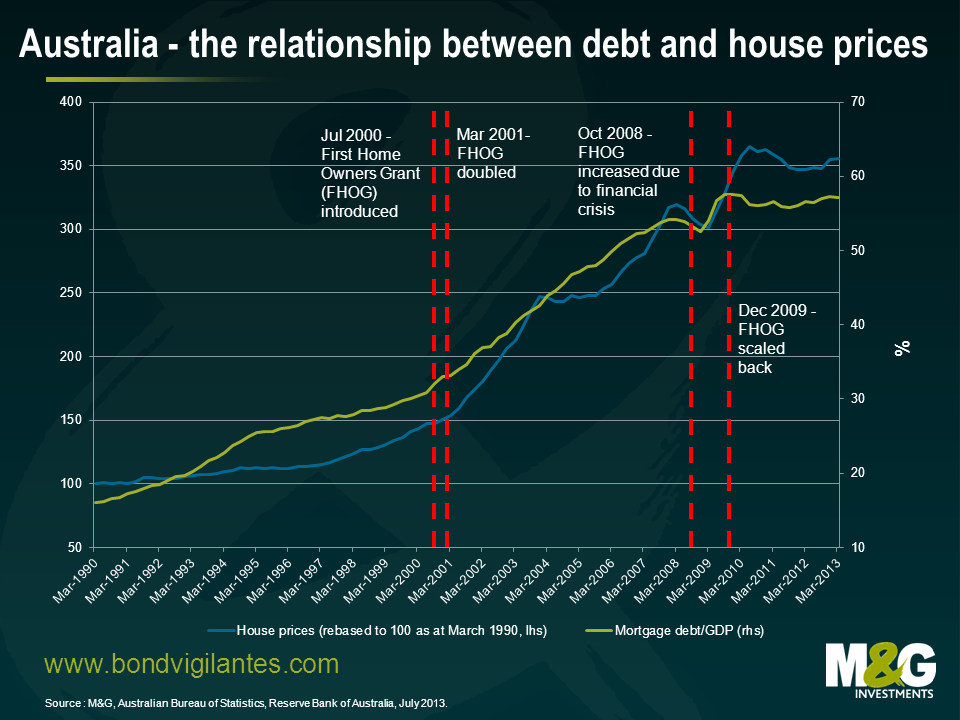

We have written before that the Australian housing market worries us (see here, here and here). And with confirmation last week from the regulator that Australian financial companies have lent $1.13 trillion AUD in residential loans to facilitate the increase in house prices we are even more worried. In the background, national papers have been reporting that auction clearance rates have been higher than 80% for almost two and half months and that Chinese buyers are increasingly entering the market due to government restrictions on purchases at home.

The regulator must keep an eye on debt levels and the quality of banks loans to individuals. In Q2 2013, financial institutions lent $79bn to home buyers. $31bn of this was interest-only and low-documentation lending. As we all know this is the area where mortgage delinquencies will first occur in an economic downturn. In Australia, there is a close relationship between debt/GDP levels and house prices. Should the banks be forced to rein in lending, we could see some big ramifications for the housing market pretty quickly.

Australian housing is showing all the signs of a bubble. When lenders start resorting to the cute little kid to shift 95% loan-to-value mortgages you have to wonder how much longer this can go on.

How has the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) reacted to this asset price bubble and the risks that it poses to financial stability? By stating that there is no bubble. Dr Malcolm Edey, who is responsible for financial stability at the RBA, stated last week that: “We’re in one of the higher-than-average periods at the moment, but we shouldn’t be rushing to reach for the bubble terminology every time the rate of increase in house prices is higher than average, because by definition that’s 50 per cent of the time. You’re just going to be unrealistically alarmist by making that call every time that happens.” So it appears the RBA, much like the Federal Reserve in the US under Alan Greenspan, would be very hesitant to raise rates to reduce any “froth” that may develop in areas of the Australian housing market.

It is easy to see why the RBA would avoid such an action. Higher rates, in a world where interest rates are near zero in the developed markets, would drive the AUD higher and reduce whatever little competitiveness the manufacturing and export sector had after years of an overvalued AUD in a globalised economy.

The catalyst for any house price correction in Australia will be the labour market. And leading indicators aren’t great. The Australian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy released a report yesterday showing that unemployment amongst its members had increased from 1.7% in July 2012 to 10.9% in July 2013.

Unlike the RBA, we think that it is time to be alarmist, particularly given our concerns around China. More than a decade of digging stuff up and shipping it to China has left Australia with all the telltale symptoms of Dutch disease. The mining industry is not only one of the largest employers in the country, it is famously one of the best paying as well (who hasn’t heard the anecdotes of cleaners being paid $100k a year to clean the miners living quarters?). Should the resources boom fizzle out, as it most likely will in conjunction with a China slowdown, hundreds of thousands will face losing their jobs across the economy. Not only that, we will see a massive impact on consumption within the economy as consumers tighten their belts to try and pay their ultra-high mortgage payments (Aussies will have to quickly deploy the savings they have been building up – the household saving ratio has increased from -2.4% in 2002 to 10.8% today). With unemployment and mortgage defaults rising, the RBA will hit the zero interest rate bound and embark on quantitative easing quicker than you can say “why didn’t we see this coming?”

Most economists see an orderly rotation away from the mining sector as the driving force of the economy to the services sector. The main reason they point to is that a sharply lower AUD should allow sectors like manufacturing and tourism to thrive again. In terms of the housing market, many point to significant under supply and full recourse loans as protection against a meaningful correction in Australian house prices to saner levels. The consensus expects modest gains in house prices for the foreseeable future.

Personally, I am not so sure. Can we really expect a hollowed out manufacturing sector to soak up the excess workers that the mining sector is shedding at a record rate? Remember when central bankers told us the sub-prime crisis was contained? Or the tech boom of the late 90s when everyone was an I.T. expert? Or perhaps it was that developments in Thailand were unlikely to spread and affect developed markets in 1997?

I’ll put my hands up; I’ve thought that a meaningful correction has been coming for at least the five years I’ve been in London. But I haven’t been as convinced as I am today that we are close to the end. There is enough evidence to suggest that Australian central bankers and policymakers should be greatly concerned and the absence of any meaningful debate in the recent election suggests there is limited political will to address any housing affordability problems that Australia is experiencing. I am amazed that young people all over Australia have not made more of an impact on the national debate on house prices. But then again, those born in the 80s and 90s think that rising house prices and economic prosperity is a way of life, so why not borrow eight times your income and leverage yourself up to buy your first house? You can always sell it in five years’ time and buy a better one.

Australia’s national sporting teams may recover from their current downturn. Hopefully the cricketers will in time for the Ashes which begin in November. Whether the Australian economy can survive the double-whammy of a China slowdown and housing correction is another story.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

18 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox