Mortgage intervention – the UK government’s unconventional attempt to ease monetary policy

Since we started writing these blogs almost 7 years ago we have spent an understandably great deal of time discussing Bank of England monetary policy in the UK, initially with regard to conventional interest rate policy and now in the context of the unconventional policies we see today.

The most recent unconventional twist for monetary policy is not emanating from the Bank of England itself, but is effectively coming directly from the government. The Help to Buy home ownership scheme is a direct attempt to make the monetary transmission system more effective, with its supporters claiming it is a way to get free markets working so that good borrowers can access appropriate funding, while its detractors claim it’s stoking a housing boom and fuelling the next crisis.

One of the ways that monetary policy in the UK works is through the housing market. Interest rate changes reduce the cost of financing, which increases disposable income, or allows an individual to own a larger house for the same mortgage payments. This creates immediate wealth via higher disposable income, economic activity via the associated services and goods consumption that occurs with house moves, and a wealth effect as house prices rise.

It has been pretty plain that the connection between official interest rates and rates available in the real world has broken down during the financial crisis, as the banking system has been repressed from a capital, confidence, and regulatory point of view. The authorities have tried to counteract this by providing capital, encouraging the raising of capital, and providing huge amounts of liquidity. However, the traditional mechanism of rates feeding into the real economy in the UK via the housing channel was limited.

The Help to Buy and other schemes such as Funding for Lending are attempts to mend the disconnect between official rates, the banking system, and the real economy. Therefore they should be welcomed as an attempt to make monetary policy work again. This unconventional policy appears to be working. The UK housing market is strong. This week’s RICS survey showed that home sales in September reached a near four year high and the market is improving across the country, not just in London. As the chart below shows, there is potential for further strength in the future too, with sales expectations for the next three months reaching new highs.

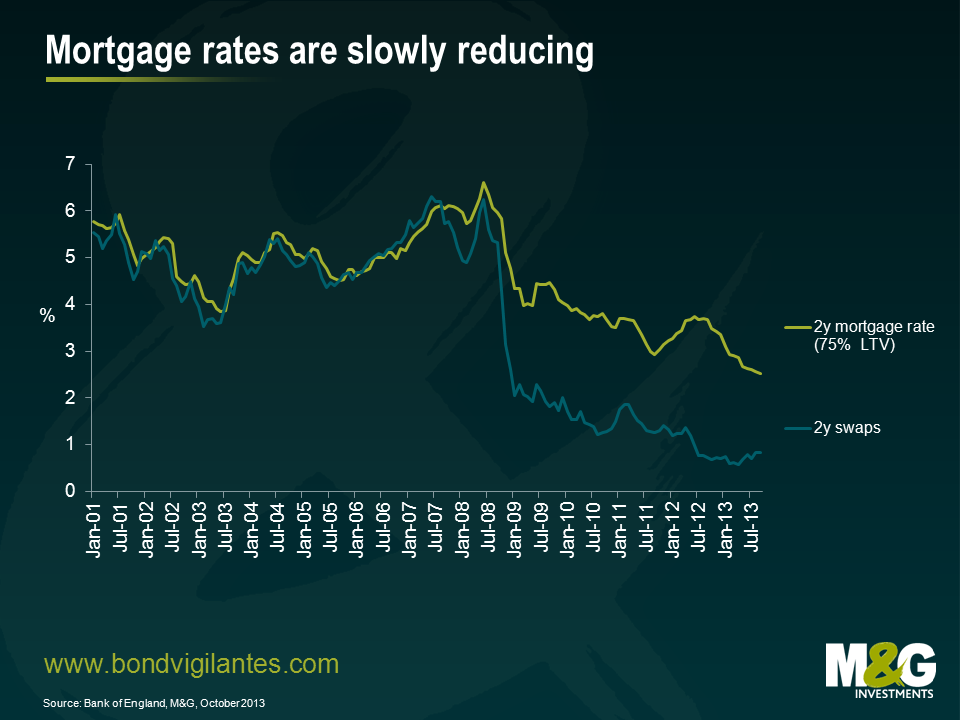

My next chart shows 2 year fixed mortgage rates plotted against 2 year swap rates. As you can see, although swap rates plummeted from late 2008, when official interest rates were slashed in the height of the credit crisis, these falls were not passed on to the same degree in the real world through mortgage rates. But they are now becoming slowly more aligned, as swap rates have been gradually rising recently and mortgage rates continue to fall. This is obviously good for the housing market and the economy. This effect is about to get bigger as the availability of low deposit mortgages should provide a strong boost to all the activity associated with housing.

Why has it taken so long to introduce this unconventional measure? It could have been a reluctance to stoke the housing market following the last crash, a belief that these kind of non-standard measures would not be needed, or it could be that it has been timed now in an attempt to push the economic cycle in line with the UK political cycle. The latter seems to be a consequence of the measures. They have been introduced in time to boost the housing market and the economy, and are set to expire before the election to encourage a rush of buying, as occurred with the removal of mortgage interest tax relief in the 1980s.

The UK economy looks set to be strong in the run up to the election as the disconnect between official rates and real activity gets resolved. The liquidity trap is being solved by government action. For better or worse, the UK housing market is going to be at the centre of UK economic activity once again.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

18 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox