High yield: bullish or blinkered?

I recently attended JP Morgan’s annual US high yield conference. It’s one of the best conferences around: well attended, and with more than 150 companies, panel discussions and specialist presentations. As such, the topics covered give a good flavour of the market’s latest thinking.

Unsurprisingly, many of the well-rehearsed arguments in favour of high yield resurfaced once again, with presentations focused on the following:

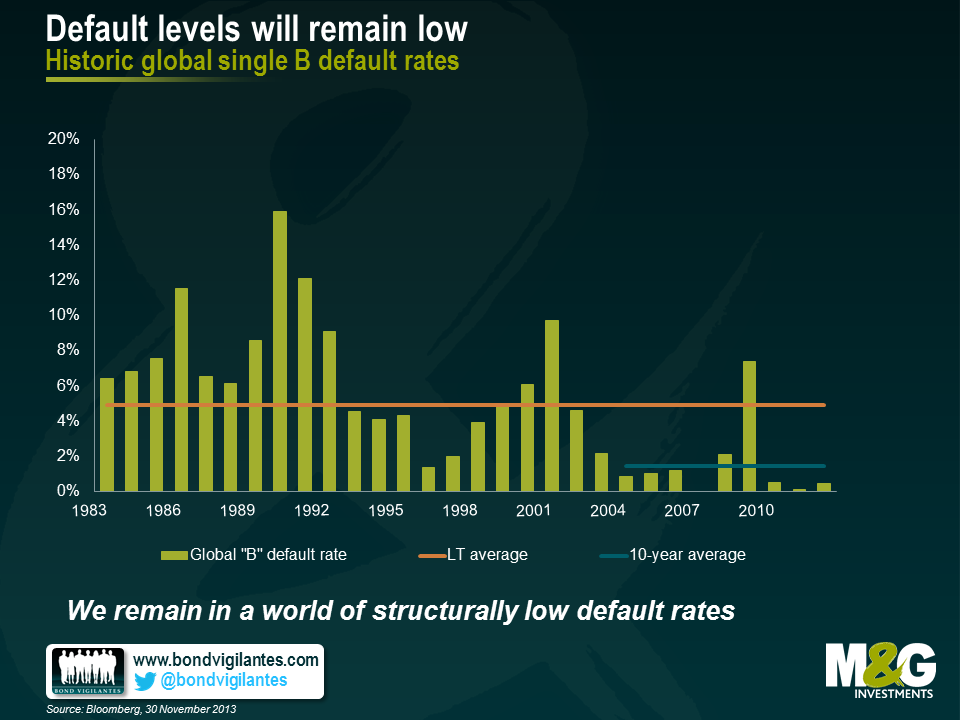

- The structurally low default rate (see chart below), largely a function of accommodative central bank policy, limited refinancing risk and growing investor maturity, with spreads over-compensating as a result.

- Projections that US high yield will outperform other fixed interest asset classes in 2014, returning 5%-6% (leveraged loans likely to deliver 4.5%).

- Room for spreads to tighten further given that they remain over 100+ bps back of the lows in 2007. Currently 378bps vs 241bps in May 2007.

- How refinancing, rather than new borrowing, is driving the majority of issuance in the US. Refinancing accounted for 56% of issuance in 2013, though down from 60% in 2012.

- The need for income in a low interest rate world is providing a strong technical support, evidenced by $2bn+ of mutual fund inflows into the US high yield market year to date. Significant oversubscription for the vast majority of new issues has also been a notable feature of the market for some time now.

- The short duration nature of the asset class – particularly attractive in an environment of potentially rising rates. Modified duration for US and European high yield is 3.5 years and 3 years respectively. This compares to 6.5 and 4.5 years for the investment grade equivalents.

Now these are all relevant arguments in favour of the asset class, and indeed I believe that US high yield will likely be one of fixed income’s winners in 2014. What did surprise me, though, was the almost total absence of discussion around some of the headwinds that it faces.

For example, presentations seemed to gloss over the fact that much of the good news, from the perspective of default rates at least, has arguably already been priced in. The market is unlikely to be surprised by another year of sub-2% defaults, rather the risk lies in an outcome that sees a higher default rate than anticipated by the consensus, even if that is difficult to envisage right now.

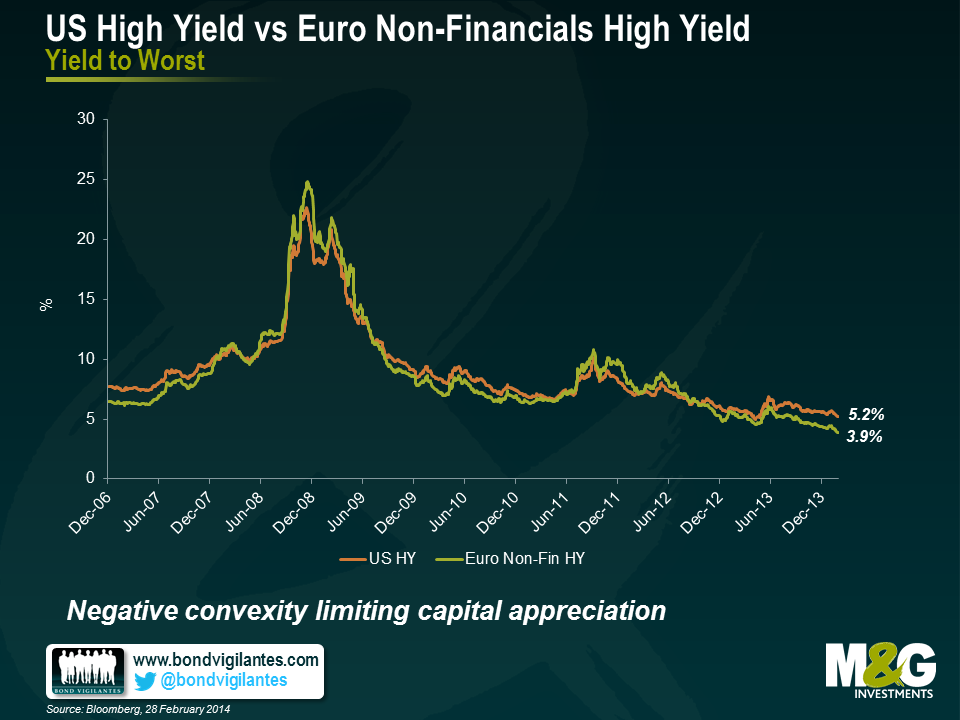

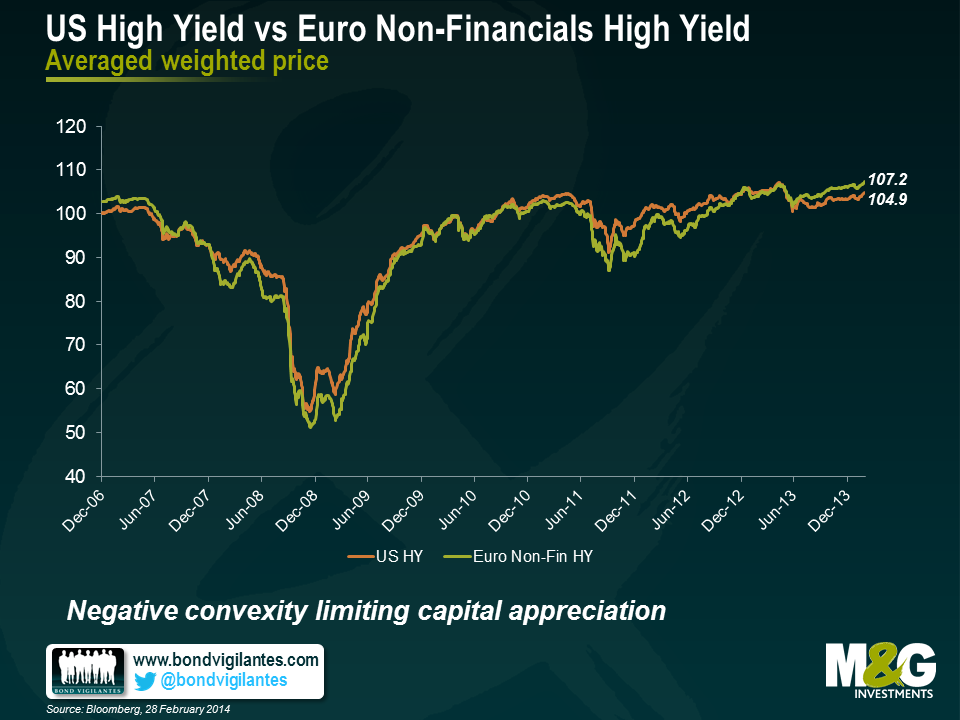

Other challenges are presented by liquidity (while this has improved since the immediate aftermath of the credit crunch, investment banks are still reluctant to offer liquidity given the high capital charges they face and the low yields currently on offer); by the lack of leverage available to end investors compared to 2006-7, when banks had the ability, strength and desire to lend to those investors on margin; and by the increasing negative convexity the market faces at the moment.

With US high yield paper already trading at an average price of 105 and as high as 107 in Europe (see chart above), the threat of bonds being called will act as a cap on further capital appreciation. And, of course, the flip side of these high prices is low all-in yields. With these standing around 3.8% on the European non-financial high yield index and 5.2% on the US high yield index, investors can only question how much lower they can go.

Perhaps in this environment, with inflation ticking along comfortably below 2%, investors should accept that a nominal return of 5-6% looks decent. That said, returns this year are likely to be driven by income rather than capital appreciation, and may well look skinny versus previous years. As I said before, I’m still constructive on high yield, but after the stellar returns in the past few years, we must be careful to avoid being blinkered.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.