What could possibly derail the global economy?

Things are looking pretty good for the global economy right now. The U.S. Federal Reserve is slowly reducing quantitative easing, China is continuing to grow at a relatively rapid pace, the Bank of England is talking about rate hikes, and the central banks of Japan and Europe continue to stimulate their respective economies with unconventional and super-easy monetary policy. The International Monetary Fund expects growth in the developed economies to pick-up from a 0.5% low in 2012 to almost 2.5% by 2015, while emerging market economies are expected to grow by 5.5%.

Of course, it is notoriously difficult to forecast economic growth given the complexity of the underlying economy. There are simply too many moving parts to predict accurately. This is why central banking is sometimes described as similar to “driving a car by looking in the rear-view mirror

With this in mind, it is prudent to prepare for a range of possible outcomes when it comes to economic growth. Given the consensus seems pretty optimistic at the moment, we thought it might be interesting to focus on some of the possible downside risks to global economic growth and highlight three catalysts that could cause a recession in the next couple of years. To be clear, there are an infinite range of unforeseen events that could possibly occur, but the below three seem plausibly the most likely to occur in the foreseeable future.

Risk 1: Asset price correction

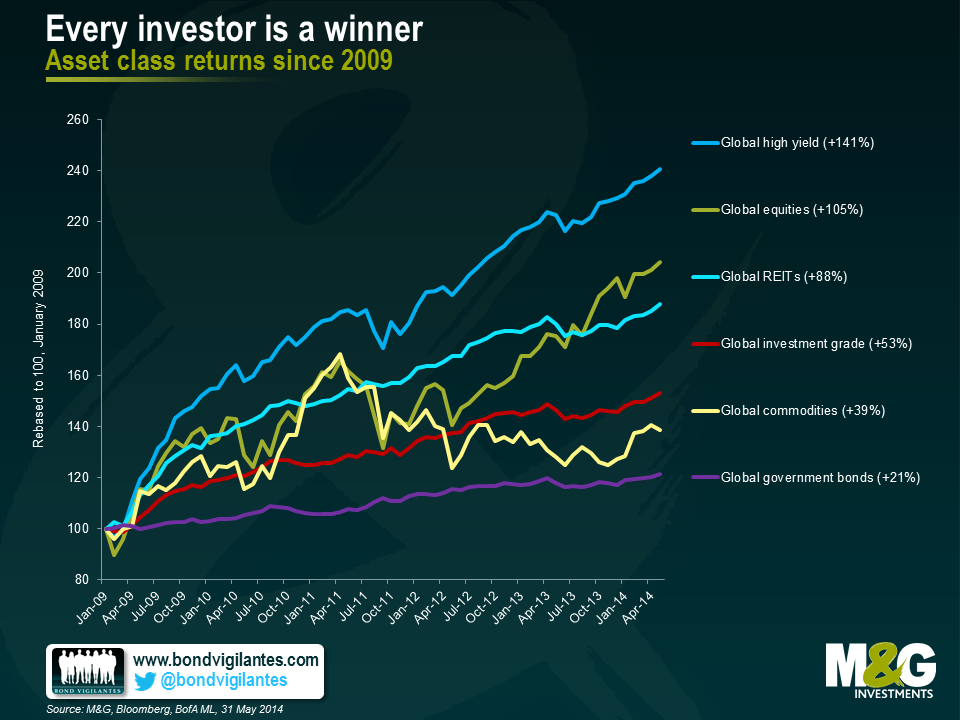

There is no question that ultra-easy monetary policy has stimulated asset prices to some degree. A combination of low interest rates and quantitative easing programmes has resulted in fantastic returns for investors in various markets ranging from bonds, to equities, to housing. Investors have been encouraged by central banks to put their cash and savings to work in order to generate a positive real return and have invested in a range of assets, resulting in higher prices. The question is whether prices have risen by too much.

This process is likely to continue until there is some event that means returns on assets will be lower in the future. Another possibility is that a central bank may be forced to restrict the supply of credit because of fears that the economy, or even a market, is overheating. An example of this is the news that the Bank of England is considering macro-prudential measures in response to the large price increases in the UK property market.

In addition, there is a surprising lack of volatility in investment markets at the moment, indicating that the markets aren’t particularly concerned about the current economic outlook. Using the Chicago Board Options Exchange OEX Volatility Index, also known as the old VIX (a barometer of U.S. equity market volatility) as an example shows that markets may have become too complacent. Two days ago, the index fell to 8.86 which is the lowest value for this index since calculations started in 1986. Previous low values occurred in late 1993 (a few months before the famous bond market sell-off of 1994) and mid-2007 (we all remember what happened in 2008). The lack of volatility has been something that several central banks have pointed out, including the U.S. Federal Reserve and the Bank of England. The problem is, it is the central banks that have contributed most to the current benign environment with their forward guidance experiment, which has made investors relaxed about future monetary policy action.

If these events were to occur, we could see a re-pricing of assets. Banks suffer as loans have been given based on collateral that has been valued at overinflated prices. A large impact in currency markets is likely, as investors become risk averse and start to redeem assets. These events could spill over to the real economy and could therefore result in a recession.

Risk 2: Resource price shock

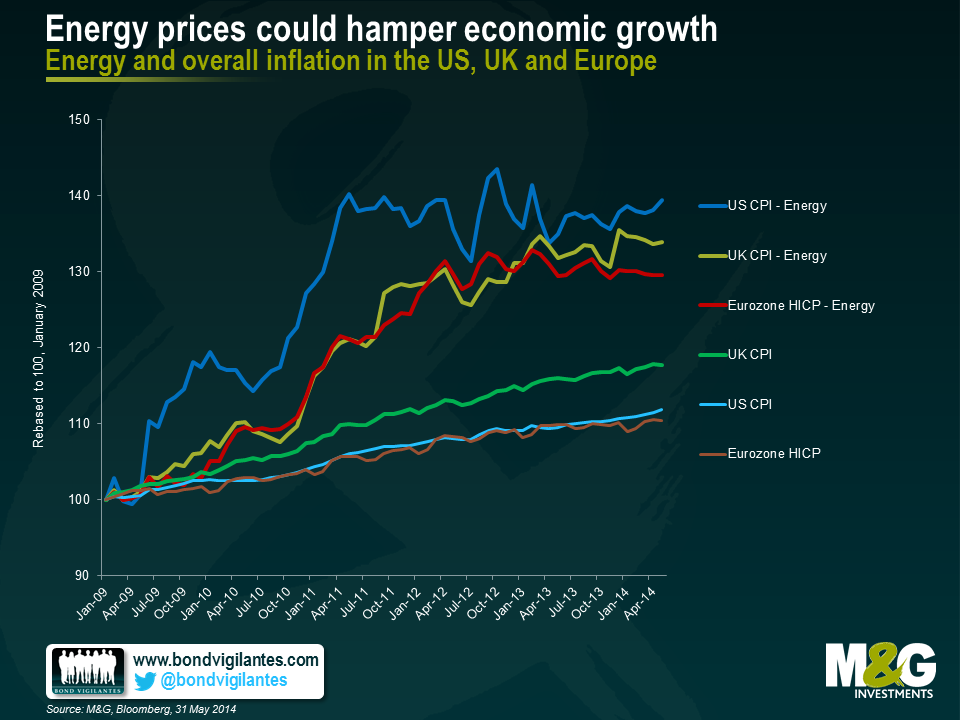

It appears that the global economy may be entering a renewed phase of increased volatility in real food and fuel prices. This reflects a number of factors, including climate change, increasing biofuel production, geopolitical events, and changing food demand patterns in countries like China and India. There may also be some impact from leveraged trading in commodities. There are plenty of reasons to believe that global food price shocks are likely to become more rather than less common in the future.

As we saw in 2008, these shocks can be destabilising, both economically and politically. In fact, you could argue that the Great Financial Crisis was caused by the spike in commodity prices in 2007-08, and the impact on the global economy was so severe because high levels of leverage made the global economy exceptionally vulnerable to external shocks. Indeed, each of the last five major downturns in global economic activity has been immediately preceded by a major spike in oil prices (as the FT has previously pointed out here). Commodity price spikes impact both developed and developing countries alike, with low-income earners suffering more as they spend a greater proportion of their income on food and fuel. There is also a large impact on inflation as prices rise.

A resource price shock raises a number of questions. How should monetary and fiscal policy respond? Will central banks focus on core inflation measures and ignore higher fuel and food prices? Will consumers tighten their belts, thereby causing economic growth to fall? Will workers demand higher wages to compensate for rising inflation?

Risk 3: Protectionism

After decades of increased trade liberalisation, since the financial crisis the majority of trade measures have been restrictive. The World Trade Organisation recently reported that G-20 members put in place 122 new trade restrictions from mid-November 2013 to mid-May 2014. 1,185 trade restrictions have been implemented since October 2008 which covers around 4.1% of world merchandise imports. Some macro prudential measures could even be considered a form of protectionism (for example, Brazil’s financial transactions tax (IOF) which was designed to limit capital inflows and weaken the Brazilian currency).

If this trend is not reversed, trade protectionism – and currency wars – could begin to hamper economic growth. Small, open economies like Hong Kong and Singapore would be greatly impacted. Developing nations would also be affected due to their reliance on exports as a driver of economic growth.

Many economists blame trade protectionism for deepening, spreading and lengthening the great Depression of the 1930s. Should the global economy stagnate, political leaders may face growing pressure to implement protectionist measures in order to protect industries and jobs. Policymakers will need to be careful to not repeat the mistakes of the past.

Economic forecasting is a tricky business. It is important that investors are aware of these risks that may or may not eventuate, and plan accordingly. The outlook may not be as rosy as the consensus thinks it is.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

18 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox