“A grip on the public finances”. Redeeming war loans as UK borrowing rises.

As you know, we’ve always been fascinated by the UK’s War Loans and have written about them repeatedly on this blog (here’s what we wrote in 2011 when we suggested that they should be redeemed). Bonds and war go together hand in hand, and for most of history rising government debt levels have been directly caused by the cost of financing conflicts, or the reparations afterwards. The several outstanding War Loans also tell the story of the UK’s extreme fiscal distress in the 1930s, and the quasi default that lead to a patriotic (and on the face of it voluntary) reduction in the coupon of the 5% loan down to 3.5%, and of the inflations of the 1970s and 1980s which saw the value of these undated, long duration bonds collapse to levels where their yields were higher than their prices. British Pathé has a series of great clips around the time of the £2 billion debt conversion (coupon reduction) mentioned above, including Neville Chamberlain presenting his plan on the deck of a ship. At the time he was regarded as a media genius and newsreel gold apparently – the Russell Brand of his day.

On Friday HM Treasury announced that £218 million of one of the smaller, and higher couponed, War Loans will be repaid at par (100). This bond was issued in 1927 to refinance some WW1 debt. There’s obvious speculation that the rest of the War Loans, including the £2 billion 3.5% issue, might also be redeemed if yields stay low (disclaimer: we own that, and other similar gilts, and it would be nice if it happened!).

The thing that struck me from the announcement though was the Chancellor’s comment that “we are only able to take this action today thanks to the difficult decisions that this government has taken to get a grip on the public finances … (and) the fact that we will no longer have to pay the high rate of interest on these gilts means that most important of all, today’s decision represents great value for money for the taxpayer”.

I guess the bonds have indeed been a pretty sweet deal for the taxpayer – FT Alphaville calculated that in real terms the debt was inflated away such that it is effectively being redeemed at £1.82 per £100 issued (even defaulted junk bonds typically return 40p in the pound to investors!). But it is also the case that for all the talk about creating savings for the taxpayer, if this bond is refinanced at, say, 3% per year, the Exchequer benefits by just £2 million per year, in the context of a budget deficit of nearly £100 billion per year.

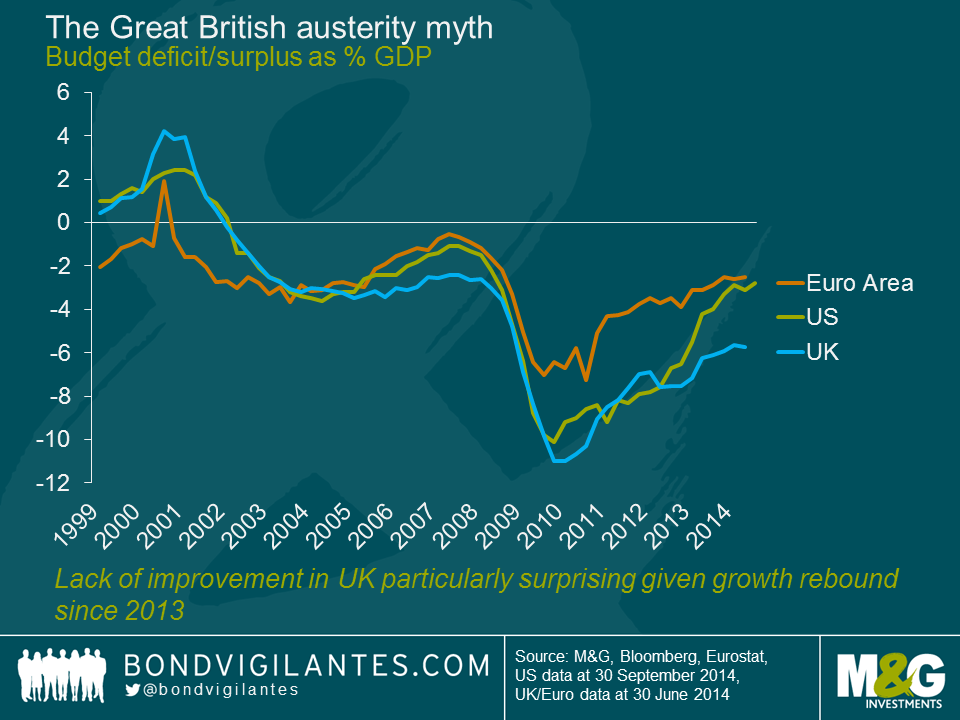

Also, has the UK government really been able to repay this bond because of the “tough grip” on the public finances? Not only did the UK lose its prized AAA credit rating under the current government, but even now growth has come back, the UK’s deficit has been overshooting in most months this year, thanks to poor income tax receipts in particular. The Institute of Fiscal Studies (IFS) suggests that £37 billion of new austerity is required to get to a position of even balancing the books in the next 3 years or so. The chart below shows that the UK has actually seen much less improvement in its deficit as a percentage of GDP than its biggest economic peers. In fact, the UK national debt is £100 billion larger than it was a year ago and is heading towards £1.5 trillion.

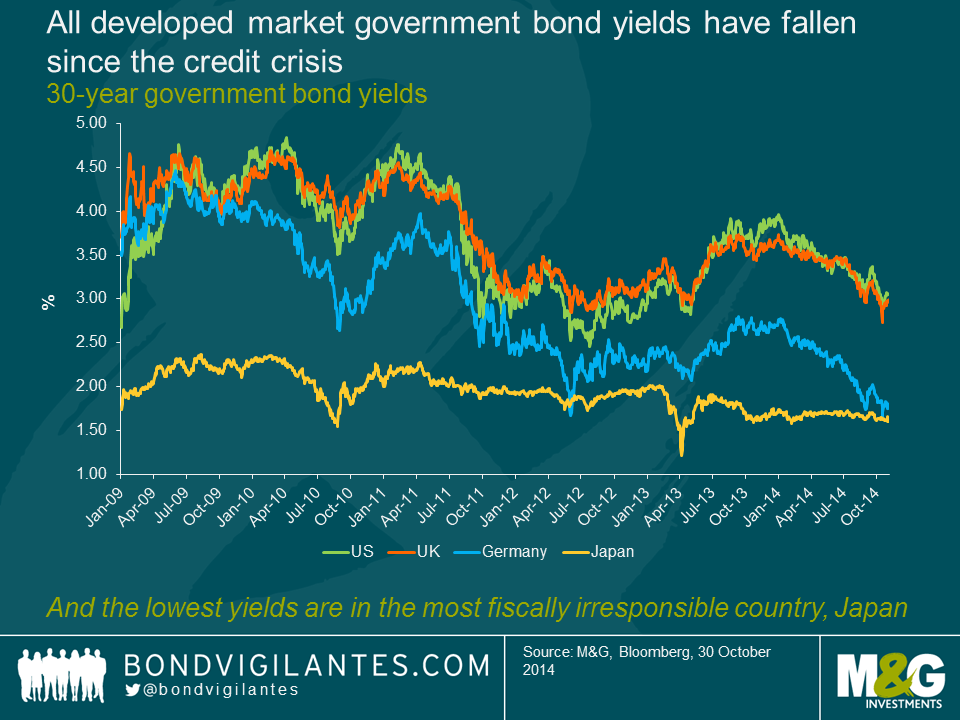

So there hasn’t been a significant improvement in the public finances in the UK. In fact, looking at the chart below you can see that the ability to refinance old perpetual bonds at low yields is nothing to do with UK specific factors. All developed market bonds have fallen in yield since the credit crisis and its aftermath. The collapse in bond yields is nothing to do with credit worthiness and all to do with a global savings glut, quantitative easing (or expectations of it in the case of Germany)and fears of secular stagnation and deflation.

Some of the lowest bond yields in the world are in Japan – 40 year government JGBs yield 1.77%. At the same time, Japan has been one of the most fiscally irresponsible countries, with a budget deficit averaging more than 6% each year in the last 20 years, a deficit in 2013 of 9.3% of GDP, and its gross public debt/GDP ratio having soared from something like 60% in the early 1990s to more than 200% now. Very low bond yields arguably say much less about fiscal discipline, and much more about the market’s view on long term nominal growth rates – if anything, you could argue that rather than something to celebrate, low bond yields – and the redemption of the War Loans – are a worrying signal since they suggest very low economic growth potential.

Will the 3.5% War Loan go the same way as the Consol 4s? Obviously the lower coupon sets the bar a bit higher for its redemption, and the bond price at just under 92 means that investors would be gifted 8 points of capital return. The other concern that the Debt Management Office has is that bond yields could rise substantially between an announcement like Friday’s and the date when they repay the money next year, such that it looks like the bonds should have been left outstanding. So there is an “avoidance of embarrassment” factor too which means that the economic decision needs to be clear cut rather than borderline. The timing of 3.5% War Loan’s coupon payments might make an announcement in an early pre-election Budget attractive for the government if yields remain around current levels as repayment would likely be on a coupon date, redemption requires 90 days’ notice and therefore 1st June could be achievable.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

18 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox