Negative rates – a tax on saving? Don’t forget about actual tax

There has been much discussion recently that by introducing negative rates central banks are effectively taxing savings. This is self-explanatory, and is one of the criticisms of how negative rates can distort economic behaviour. This however is not a new phenomenon. Let’s not forget that money has always been effectively clipped by the traditional enemy of savers – inflation. Fortunately, holders of cash have traditionally been compensated for depositing it in a bank account by receiving interest payments. But is this something that is now at threat with negative rates?

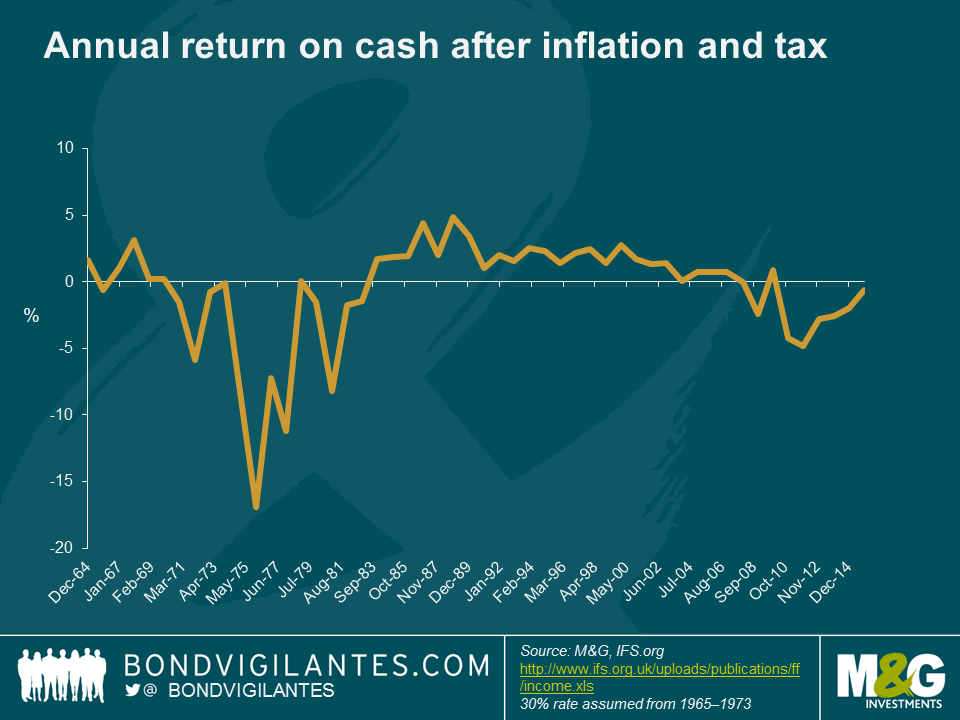

If you take the Bank of England rate as a proxy for the interest earned on cash and adjust for inflation (i.e. subtracting RPI from base rates), although negative nominal interest rates are a new phenomenon, real negative rates are not. If we expand this thinking to include the historic rate of basic income tax, we can attempt to fully depict what can be considered the real rate of return on cash. This gives a more accurate reflection of what savers have actually earned in real disposable income per annum and as you can see from the chart below, this has been negative in the UK for much of the past ten years.

Given the recent outcry regarding the effect of negative rates on savers one has to believe that they are suffering from the economic concept of money illusion. This ‘savers illusion’ is a function of them focusing solely on the nominal rate and ignoring the true level of return after inflation and tax. (Remember that negative interest rates are more likely to occur in a deflationary environment, so it is still possible to earn a positive real return).

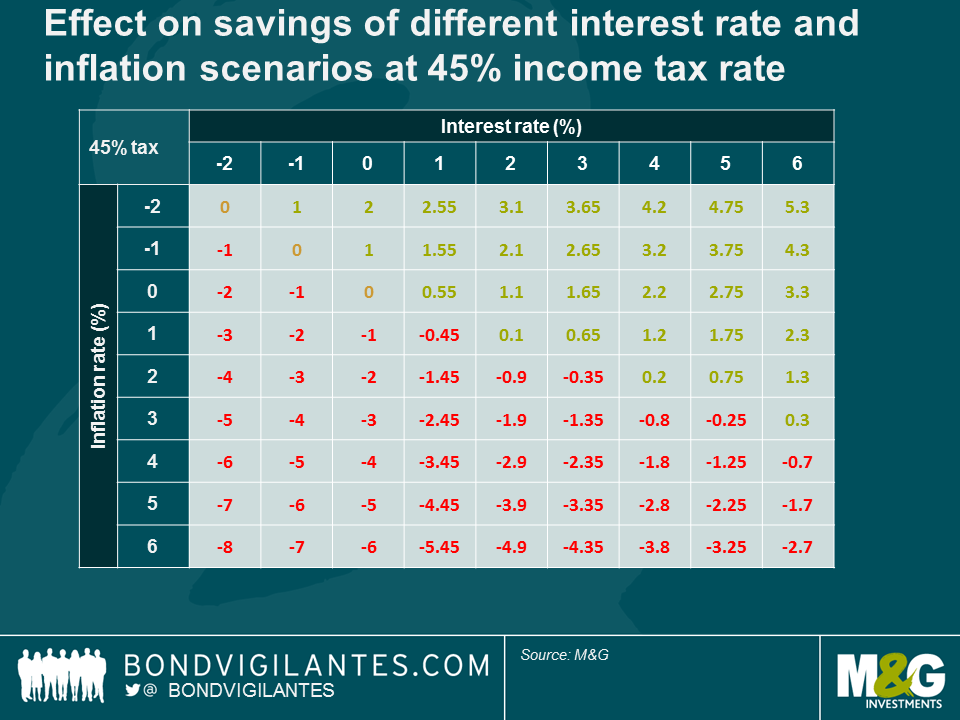

Focusing at the extreme and the 45% highest tax rate, the table below helps to illustrate the real return to these savers in various interest rate and inflation rate scenarios. As one would expect, high nominal interest rates and low inflation are beneficial for savers at all tax levels.

But one of the most interesting results occurs at zero or negative rates. The tax rate of the saver becomes irrelevant at this level; as no income is generated, no income tax can be levied. Also, although the tables illustrate a negative rate, in reality savers can get around this by holding physical cash. This is something we have talked about before, along with the elimination of currency and the nature of cash. Negative and low nominal interest rates are new, low and negative real returns both pre and post tax are not.

And whilst we are on the subject of eliminating cash it’s worth noting the ECB’s announcement about stopping printing the €500 note. By taking this action the ECB is recognising an antisocial demand for its notes (tax evasion, crime), although there remains a strong suspicion that it’s also because cash storage disrupts the transmission mechanism of monetary policy at negative rates. The ECB has, however, allowed the notes to continue to be legal tender, and presumably demand for the note will still be strong. If that’s the case could we see the €500 note trade at a premium? If so, what would that premium be? There must be some calculation based on the additional storage costs incurred by hoarding cash in lower denomination notes?

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

18 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox