Should the Bank of England start buying sterling corporate bonds again?

When the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee meets next week, the market expects that they will cut rates, especially now that even outgoing hawk, Martin Weale (who has been at the Bank for 71 meetings so far, and voted to hike 12 times, and to hold 59 times) says that he will support a reduction. A resumption of the Funding for Lending (FLS) scheme is also a possibility (many economists suggest that this was the most successful policy action taken to stimulate the economy during the UK’s Great Recession). The Bank’s remit also allows it to reopen Asset Purchase Facility, better known as Quantitative Easing. The BoE bought £375 billion of gilts from 2009 to 2012. It also bought sterling denominated corporate bonds, in the Corporate Bond Secondary Market Scheme. Largely taking place between March 2009 and March 2010, £2.25 billion of investment grade, non-financial, corporate bonds were purchased.

Whilst small in scope compared with the gilt purchases, the impact on credit spreads at a time when investors had already identified post-crisis value, was large. Borrowing costs fell substantially and the new issue market for companies re-opened. The idea that the BoE might start buying sterling corporate bonds again is now being discussed, especially as the ECB is buying euro denominated bonds at a fierce pace as part of its QE programme. On the face of it though, credit spreads are trading near their historical average rather than near Great Depression levels as in 2009, and in the banking market both the availability of credit and the spread costs to large companies – those that could borrow in corporate bond markets – are benign, if not “easy”. So why would the BoE want to start buying sterling credit again?

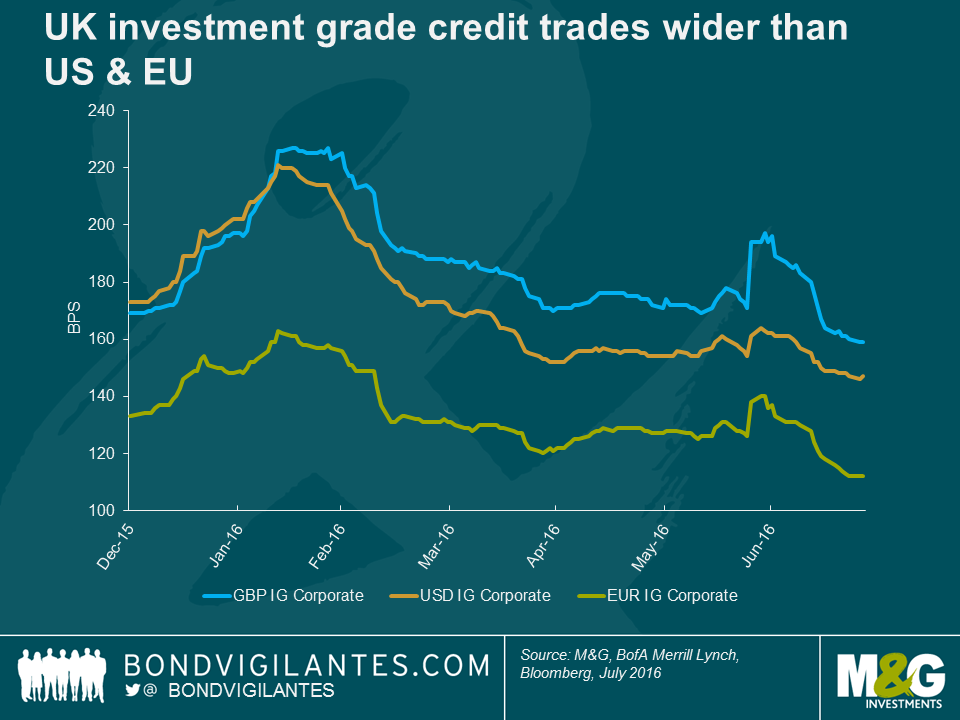

Well although credit spreads have fallen globally, especially post-Draghi’s March announcement of corporate bond purchases, sterling credit has definitely lagged. Using BofA Merrill Lynch indices to compare market levels, the UK investment grade corporate bond market trades at a spread of 161 bps over government bonds, compared to 148 bps in the US and 114 bps in Europe. Now there’s definitely a compositional bias here – for example the UK corporate bond market is longer dated and you might expect a risk premium as a result. But when you look at spreads on a “same name, similar maturity” basis, the UK corporate bond market is still wide. For example Deutsche Telekom bonds with a 2030 maturity trade with a spread of gilts plus 108 bps in sterling, or bunds plus 90 bps in euros. Johnson & Johnson 2023 bonds trade at gilts plus 40 bps, or US Treasuries plus 19 bps. Tesco 2024 bonds have a spread of 314 bps over gilts, versus the euro 2023s spread at 257 bps over bunds.

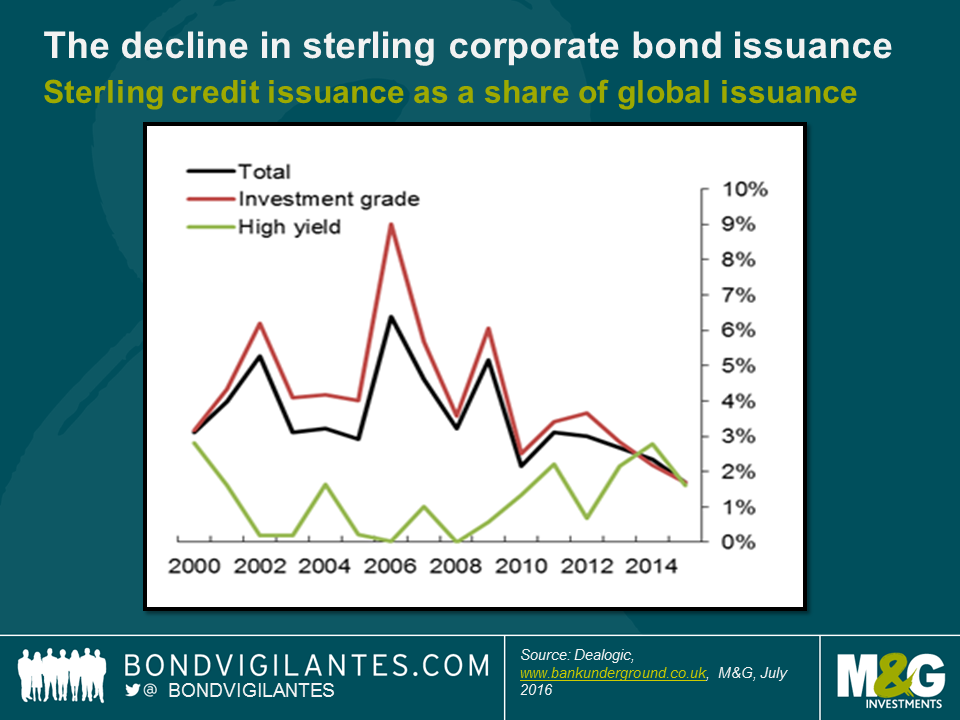

Because the UK credit market trades wider than other big capital markets, it deters corporate treasurers from issuing in sterling. It’s more expensive. Most big companies can choose where they issue debt, and they can hedge away the currency risks using swaps, leaving just the “pure” cost of the debt to consider (they must also take into account the cross currency basis swap costs, but that’s another story). This has become a vicious circle for the UK debt market. As companies see cheaper funding available elsewhere, they issue in US dollars or euros, which reduces liquidity in the sterling market, which leads to wider credit spreads, which makes it more expensive to issue in sterling. And so on. The BoE examined some of the factors behind the fall in sterling issuance on its excellent Bank Underground blog in April this year. In it they showed that annual gross sterling issuance has almost halved since 2012, and sterling’s share of global issuance last year was the lowest on record.

The BoE staff ascribe the fall in sterling issuance to three reasons. Firstly, a concentrated sterling investor base and mergers in the industry meant that some large institutions were effectively “full” of some names, and a lower number of participants meant that it could be hard to get deals done, meaning higher yields were required to entice buyers. Secondly, changes in annuity rules reduced the demand for long dated credit. And finally, the growth of the euro denominated corporate bond market since 1999 has led to it gaining “critical mass” for both issuers and buyers.

If the BoE were to restart its corporate bond programme, it could drive credit spreads down to something in line with euro and dollar issuance through ongoing, price insensitive buying. Lower UK credit spreads relative to the other major markets would provide some incentive for corporates (both domestic and global) to start issuing sterling bonds once more.

In a post Brexit world, with a threat of financial market activity moving away from London, the reinvigoration of a declining UK corporate bond market appears attractive. Whilst the reduction in financing costs for UK based corporates might be marginal, it too would be welcome if the weak post-Brexit survey data is correct in predicting a sharp downturn in economic activity.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

18 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox