Changes in corporate bond market liquidity and the opportunities they present

One of the prevailing features of the last few years has been the increasing prominence of discussions regarding market liquidity and the seemingly downward trajectory it has taken across fixed income markets. This had led many market participants to question the resulting implications for market stability and volatility.

It makes sense then to try and understand the driving factors behind these trends and the potential pitfalls and opportunities they present for active managers. As someone with experience of attempting to physically transact the various trade ideas and strategies that have been employed, I hope I can lend some insight.

Traditionally, markets are deemed to be liquid when investors are able to transact in them with low cost, little delay and at, or near, the current ‘market price’. Additionally, it is important to note the difference between normal market liquidity, i.e. balanced markets (where there are a roughly even proportion of both buyers and sellers) and stressed markets where the direction of orders is extremely imbalanced.

The extent to which corporate bonds markets are, or ever have been liquid by the above definition is questionable for a number of reasons. Namely, the relatively heterogeneous nature of the asset class makes trading difficult, with issuers having many bonds in existence, with many different characteristics, all being quoted and traded in varying quantities and consistencies. At the same time, the nature and breadth of the investor base is often highly variable, with some varieties of large institutional investors, who may often hold assets for long periods or even to maturity, making up a large proportion of an issue, resulting in lumpy and infrequent trading. This means that matching buyers and sellers at any given time in the market is usually not possible; necessitating the use of intermediaries, namely market makers – in most cases a bank or occasionally a broker. In less widely quoted bonds, this can make liquidity highly dependent on the whims of a select few traders.

Whilst these factors have always been present to a greater or lesser extent, it is fair to say the issue of liquidity and its potential decline are particularly salient now largely due to the combined effects of a period of strong growth in the size of bond markets along with the overarching tendency of the majority of market participants to all be crowding one way or another (i.e. stressed market conditions) as a result of the numerous socio-economic crises and bouts of unprecedented government and central bank intervention which have characterised the post-Lehman period. To a large extent it is the decline in the traditional role of the market maker which has drawn much of the focus, as it has been so marked and in such contrast to the growth in the size of the market.

Despite this, several key liquidity measures, namely average volumes, transaction size and bid-ask spreads all seem to indicate conditions have either recovered or at least stabilised in the years post the 2008 Lehman bankruptcy. Ultimately what this seems to illustrate is that the liquidity risk associated with corporate bond markets has in large part shifted from market makers onto investors, many of whom will, and some of whom may not, be adequately equipped to deal with it. This creates both problems and opportunities for active managers. However in times of normal market conditions, where there is a balance of buyers and sellers, it is clear that liquidity remains robust.

Further, this seems to hold true in other less developed markets also. In the case of UK, statistical evidence provided by the recent FCA occasional paper: ‘Liquidity in the UK corporate bond market: evidence from trade data’ suggests in reference to the post-Lehman period that, ‘there is no evidence that liquidity outcomes have deteriorated in the market, despite the decline in inventory of dealers in this period.’

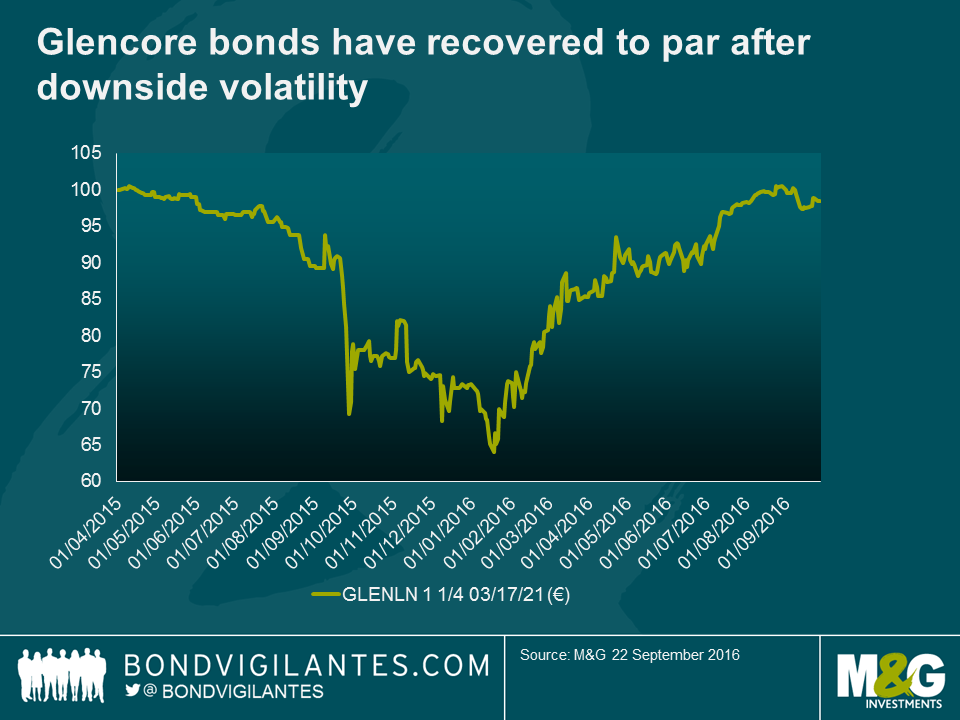

Overall, whilst this may hold true for a number of liquidity measures from a statistical standpoint in normal market conditions, it fair to say that many active market participants would disagree with the premise. The crux of the issue being that the negative effects of the change in liquidity dynamics are only truly apparent when attempting to transact in times of distress, be it for a specific issuer, industry, or the market as a whole. In these instances, there is often a clear weight of negative or positive sentiment resulting in a severe imbalance of buyers and sellers. In an environment where market makers are increasingly reluctant to provide a buffer to dampen price action, clearly volatility can be amplified. In the case of some notable recent examples such as Glencore, bonds have repriced far from any rational fundamental value, dropping in some instances 30-40% in price terms on a limited amount of volume traded before recovering much of that value in subsequent months.

Whilst it can sometimes be frustrating to transact during these periods, they crucially serve to create and highlight significant opportunities for active investors willing to adopt a contrarian view who are able to accept some short term volatility. In these instances, because an investor is in essence providing liquidity to the market, you are able to transact in large size and with a high degree of pricing power, providing a significant advantage from an execution standpoint by allowing you to achieve a price which adequately accounts for the fundamental risks involved, effectively exploiting the inefficiency in market pricing.

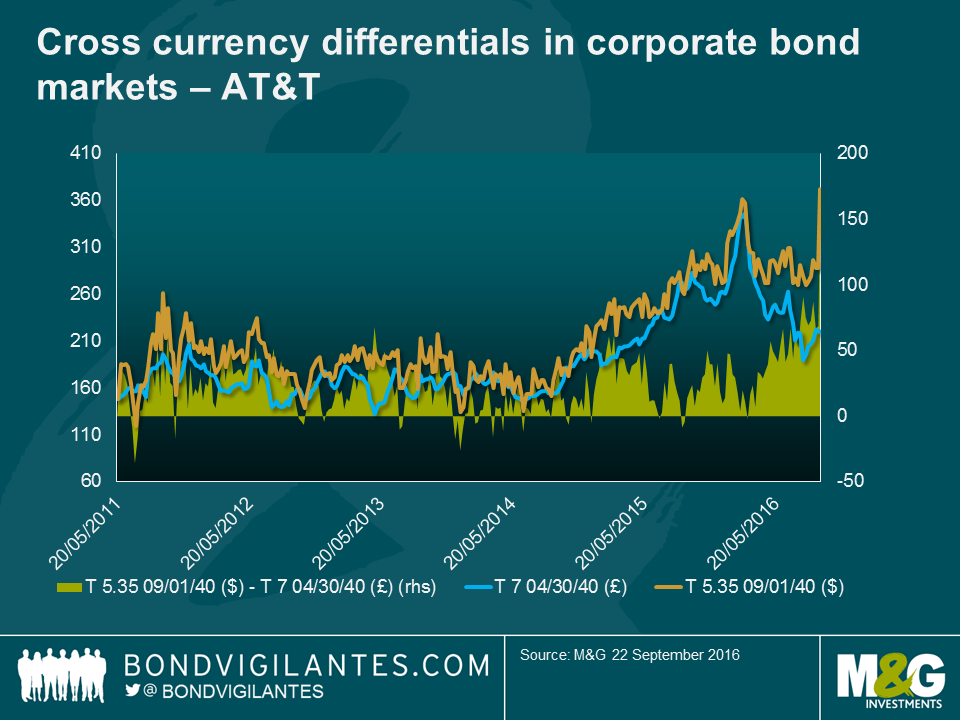

It is fair to say that whilst this is a global phenomenon, it is clear that in less developed markets, namely the UK and to a lesser extent euro corporate bond markets, these effects may be felt more acutely. A large and highly concentrated institutional investor base, combined with this withdrawal in traditional market making by banks, has led to an environment where liquidity can be somewhat transient and fragile. Binary market conditions, due largely to central bank intervention, have led to more frequent and persistent periods of stressed, imbalanced markets. Whilst again this poses challenges day to day from an execution standpoint, the price distortions that result provide significant opportunities in both the domestic markets but most clearly in highlighting relative value opportunities in international debt markets, most notably of late the US. This can clearly be seen in the example of equivalent bonds of the same issuer in different currencies trading at large price discrepancies from one another from time to time before normalising again after a period of reversal potentially allowing an active investor the opportunity to achieve superior returns from essentially the same credit risk by selling one to buy the other and then reversing the trade once the relationship normalises.

A further consequence of these developments has been that trading has become highly concentrated in the most liquid bond issues, often at the expense of the liquidity in those less frequently traded. It follows that bonds that are frequently traded in large volumes are less balance sheet intensive and are therefore more attractive to trade as a market maker. It also follows that an investor who frequently requires liquidity will prefer to trade these liquid securities as they can do so easily and at low cost. The net effect is a crowding of activity in the liquid securities resulting in a sort of bifurcation of liquidity between liquid and illiquid bonds. This leads to increasingly significant price disparities between otherwise comparable bonds, allowing an active investor an opportunity to exploit the inefficiency once again by providing liquidity to the market. This is particularly apparent in the US market where trading is crowded in the most recently issued ‘on the run’ securities whilst the older ‘off the run’ securities are less frequently traded and can often become mispriced.

In all, there are a variety of factors which have contributed to marked changes in the liquidity of corporate bond markets whereby much of the liquidity risk has shifted from traditional market makers to investors, as balance sheets have shrunk and bond markets have grown considerably. Despite this, it is clear that by traditional measures markets remain liquid and function well during normal periods. However it is also clear that this liquidity can be fragile and its absence in times of distress can lead to extreme volatility and excessive mispricing. For an active investor this clearly presents several challenges but more so opportunities, both within and between markets if they are able to withstand short term volatility and manage the risks.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

18 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox