Mind the gap: what record low recovery rates mean for high yield investors

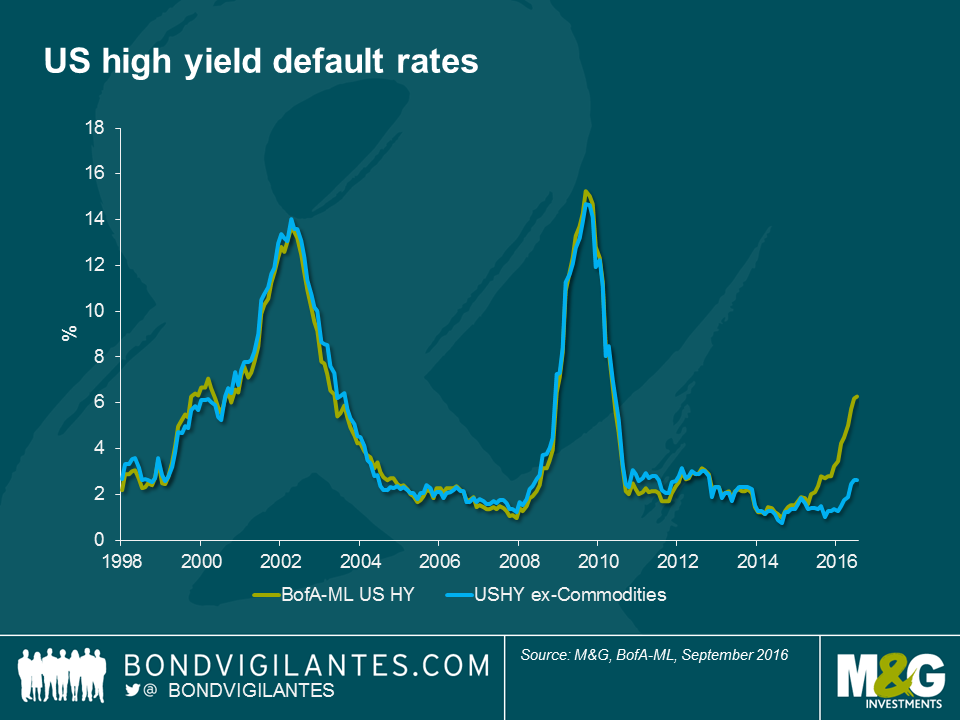

In order to assess value in credit markets, bond investors usually make some assumption about the future path of corporate default rates. This assumption generally stems from macroeconomic forecasts (strong/weak growth = low/high defaults rates) or sector specific events (like oil price movements). Following this, it is possible to get an indication of whether investors are being over- or undercompensated for investing in corporate bonds by assessing the level of credit spreads.

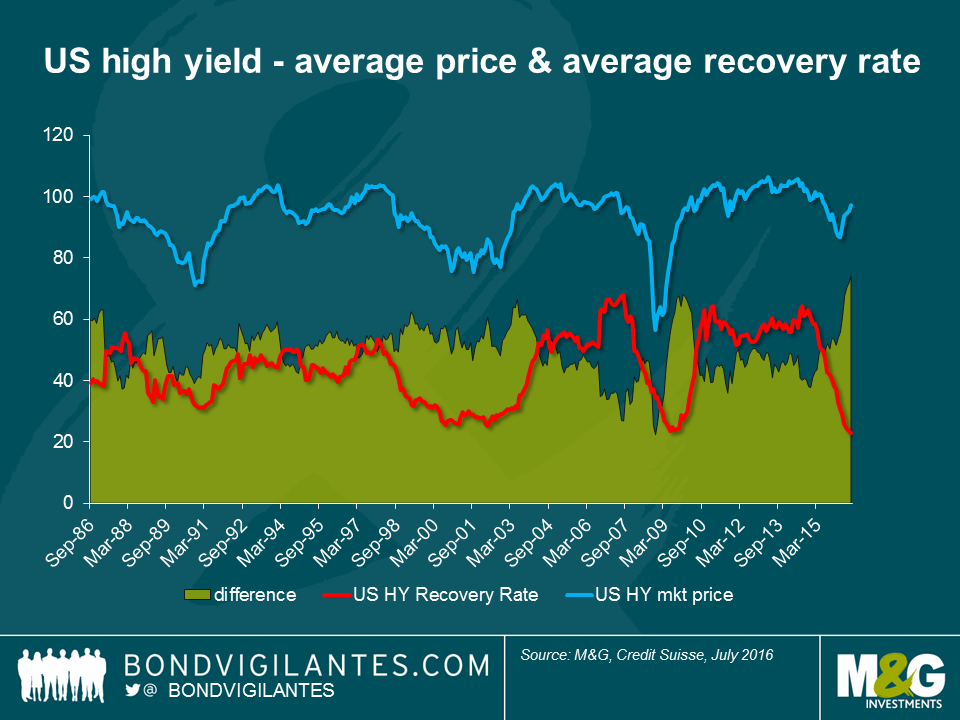

If this seems like a simplistic approach, it is. Default rates don’t give the full picture. It is important to add more information to the valuation assessment; specifically, in the event of a default how much money will investors get back? This is an increasingly important piece of information in a world where low interest rates and unconventional monetary policy has helped push high yield corporate bond prices back towards all-time high levels despite late cycle risks. Sometimes, it might be worth buying a default candidate if the level of recovery compensates for the cost of entry and the headache involved.

Over the past year and a half, US high yield recovery rates have plunged from 61% in December 2014 to a record low of only 23%. Because of the fall in recovery rates, the difference between the US high yield market price and recovery rates is at an all-time wide level. Those US high yield investors that own a bond when it defaults are now losing more money on average than ever before.

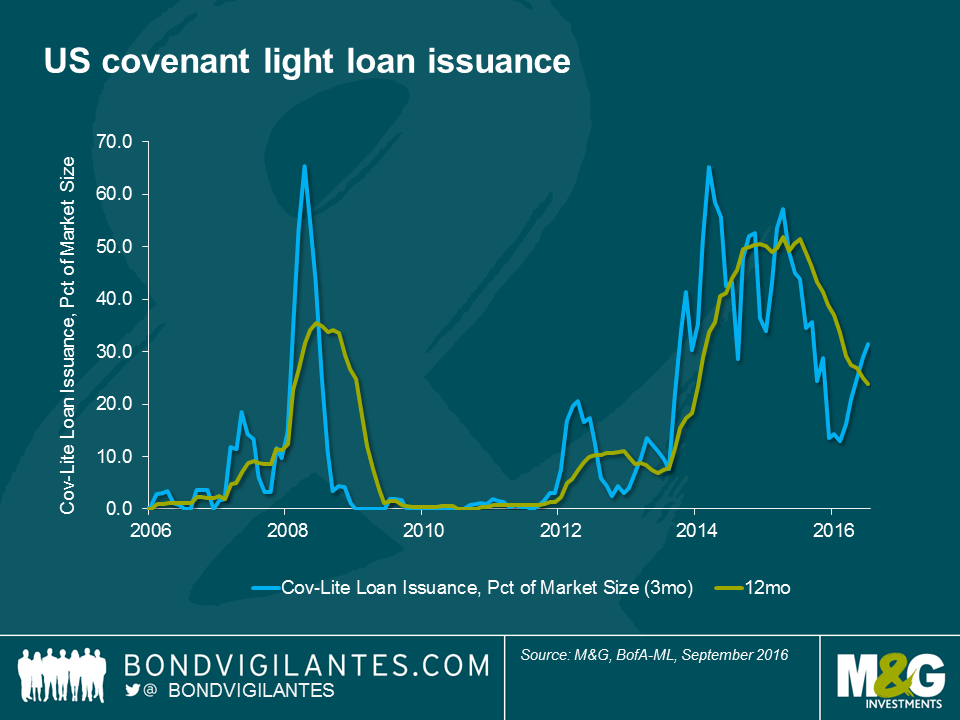

We think that there are a couple of reasons for the fall in recovery rates. Firstly, markets tend to leave investors as price takers for fear of missing the returns that other market participants are enjoying. In their quest to ‘stay invested’, bond holders will typically forgo covenant protections that will impact ultimate recoveries. One of the proxies that we pay attention to, given the close correlation to issuance standards in the high yield market, is the share of covenant lite issuance in the leverage loan market. The period of 2012 to 2015 saw a massive increase in covenant light loan issuance. This means that lenders have much weaker protection in the form of incurrence covenants rather than maintenance tests. The US high yield energy market is a case in point. Underpinned by $100 oil price, high yield investors paid far too little attention to bond documentation, leaving significant room for creditors to be “primed” (the act of granting a new lender higher claims priority over an existing creditor).

We think that there are a couple of reasons for the fall in recovery rates. Firstly, markets tend to leave investors as price takers for fear of missing the returns that other market participants are enjoying. In their quest to ‘stay invested’, bond holders will typically forgo covenant protections that will impact ultimate recoveries. One of the proxies that we pay attention to, given the close correlation to issuance standards in the high yield market, is the share of covenant lite issuance in the leverage loan market. The period of 2012 to 2015 saw a massive increase in covenant light loan issuance. This means that lenders have much weaker protection in the form of incurrence covenants rather than maintenance tests. The US high yield energy market is a case in point. Underpinned by $100 oil price, high yield investors paid far too little attention to bond documentation, leaving significant room for creditors to be “primed” (the act of granting a new lender higher claims priority over an existing creditor).

Secondly, an intended consequence of quantitative easing policies is the portfolio rebalancing effect, where investors increasingly turn to riskier assets in order to generate positive returns. One of the unintended consequences of this is the resulting misallocation of capital. Companies operating in an economic regime of quantitative easing take much longer to fail, as evidenced by the very low default rate of the last decade (with exception of the 2008 financial crisis period). In this environment, companies are incentivised to issue debt at unusually low yields, and are encouraged to allow cash to leak from the business in the form of distributions to shareholders and coupon payments to creditors. When the unfortunate time comes to wind up the business, creditors find that there is less cash to go around and more indebtedness, resulting in the low recovery rates we see today.

With recovery rates falling and default rates likely to rise from current low levels, those looking to get access high yield markets are going to have to “mind the gap” that has opened up between recovery and default rates. In an environment devoid of yield the attraction to chase income is only too understandable. Yet the risks are increasingly apparent and investors in high yield should consider their downside as well as the potential upside.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

18 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox