The front-end of the US Treasuries curve: short and sweet?

With the notable exception of the upcoming royal wedding, it would be pretty difficult to find a topic that is currently more over-analysed than the flattening of the US Treasury yield curve. On this blog as well we have pondered potential implications for credit valuations and possible counter-measures the Fed might employ. Still, one aspect that has arguably not received enough attention in the ongoing debate is the way the curve flattening impacts risk-reward profiles for US Treasury investors.

Should investors be buying Treasuries? The combination of virtually no default risk, superb liquidity and “safe haven” status is appealing. However, there are plenty of reasons to be bearish and shun Treasury exposure at the moment. Interest rate risk remains elevated in the US as it is entirely possible that the Fed decides to hike rates more forcefully than currently anticipated, should for example the diminishing slack in the US economy – in combination with a potential consumption boost due to tax reform – translate into inflationary pressures. Furthermore, Treasury supply dynamics have taken a turn for the worse due to the expanding US budget deficit and the unwinding of the Fed’s balance sheet.

Even if investors expect further pressure on valuations, from a total return perspective we cannot ignore the running yield of Treasury securities. One way of looking at the issue is a simple breakeven analysis, in which we approximate by how many basis points (bps) Treasury yields would need to rise within one year before the decline in the cash price of the bond exactly offsets the annual yield, leading to an annual total return of zero. Essentially, the breakeven quantifies the buffer capacity of a bond towards further yield rises. It is a function of the bond’s yield-to-maturity and its interest rate duration: Higher yields and lower duration numbers lead to higher breakevens and vice versa. For example, with a duration of 8.6 years and a yield of 2.96%, the breakeven for the on-the-run 10-year Treasury note (T 2.875 05/15/28) is c. 2.96% / 8.6 = 34 bps.

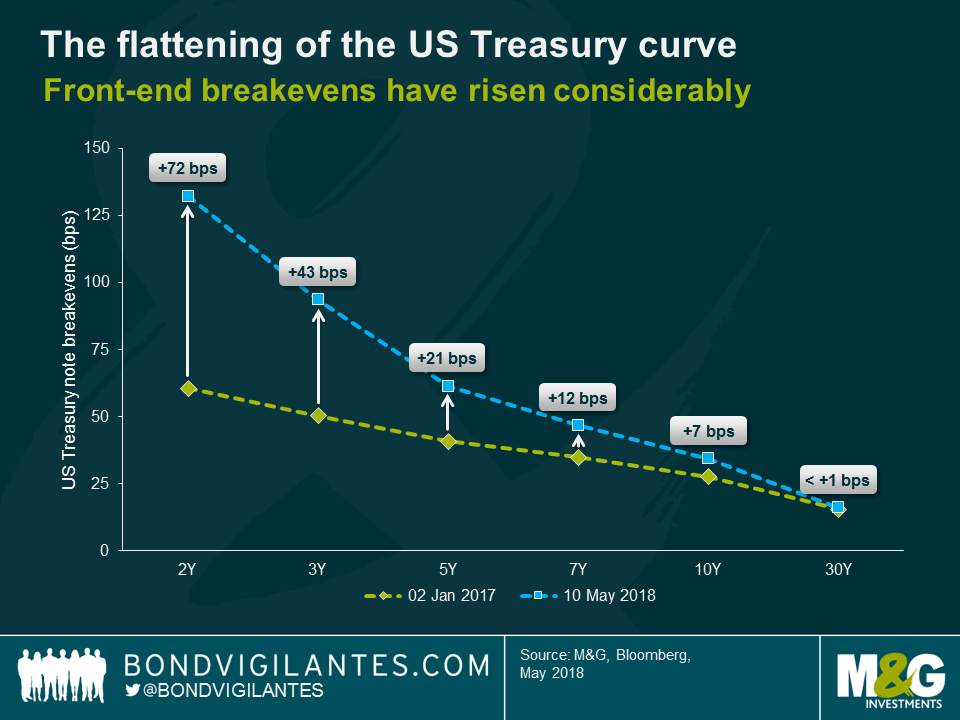

Breakevens are not static, of course, and the strong underperformance of short-dated vs long-dated US Treasury notes – i.e., the flattening of the curve – has had a tremendous impact. Surging yields at the front-end have pushed breakevens for 2Y and 3Y Treasuries up by 72 bps and 43 bps, respectively, since the beginning of 2017. In contrast, the 30Y Treasury yield has stayed more or less flat over the same period, and consequently the 30Y breakeven has hardly moved at all.

This has profound implications for investors. With a breakeven of only 16 bps, 30Y Treasury notes don’t seem to offer a particularly appealing risk-reward profile as they remain vulnerable to further yield rises. Considering the potential impact of the continuing oil price rally and the increasingly tight labour market on the US inflation outlook, a >16 bps sell-off at the long-end of the Treasury curve doesn’t strike me as implausible, to say the least. I would argue, the bear flattening of the yield curve has created a much more attractive risk-reward opportunity at the front-end. The current breakeven of 132 bps for 2Y Treasury notes, which is more than eight times higher than for 30Y Treasuries, provides a comfortable cushion to absorb even harsh yield rises, going forward.

There are a few caveats, though. The obvious risk of favouring the front-end over the long-end is of course that the US Treasury curve continues to flatten or even fully inverts. History tells us that this would be a likely scenario if the US economy was approaching a recession, which however I do not consider an immediate concern. Furthermore, the breakeven analysis does not take opportunity costs into account. The high breakeven of 2Y Treasury notes may well help investors avoid negative total returns even if yields continue to rise, but it is entirely possible that other asset classes still offer superior return opportunities. Finally, the risk-reward analysis gets more complicated for non-US Dollar investors. The costs of hedging the currency risk of US dollar positions can be material, which may reduce the relative attractiveness of US Treasury notes, particularly for Euro-investors.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

18 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox