Bahrain: avoiding the first sovereign sukuk default?

Bahrain spreads have widened in recent months, despite the rise in oil prices. The market is focusing on the $750 million Bahrain Sukuk maturing on November 22, 2018. Given that the country’s international reserves are estimated at around $2.1 billion, the country will need additional funding to repay it. The market consensus is that Bahrain will receive financial support from neighbouring Saudi Arabia and potentially other Gulf Cooperation Countries, who will seek to avoid the economic, financial contagion and pressures on their own economies and currency pegs should a default (and de-peg) ensue. The fact that the Bahrain is a relatively small economy versus its neighbours is another reason why the markets believe that it is a relatively small price to pay in exchange for diffusing the problem into the future. It is not clear, however, what kind of conditions its neighbours would demand in exchange for support. Would they require fiscal tightening, so that Bahrain’s debt dynamics can start stabilizing in a few years? But what if the market consensus is wrong, the support does not materialize and Bahrain cannot pay its sukuk?

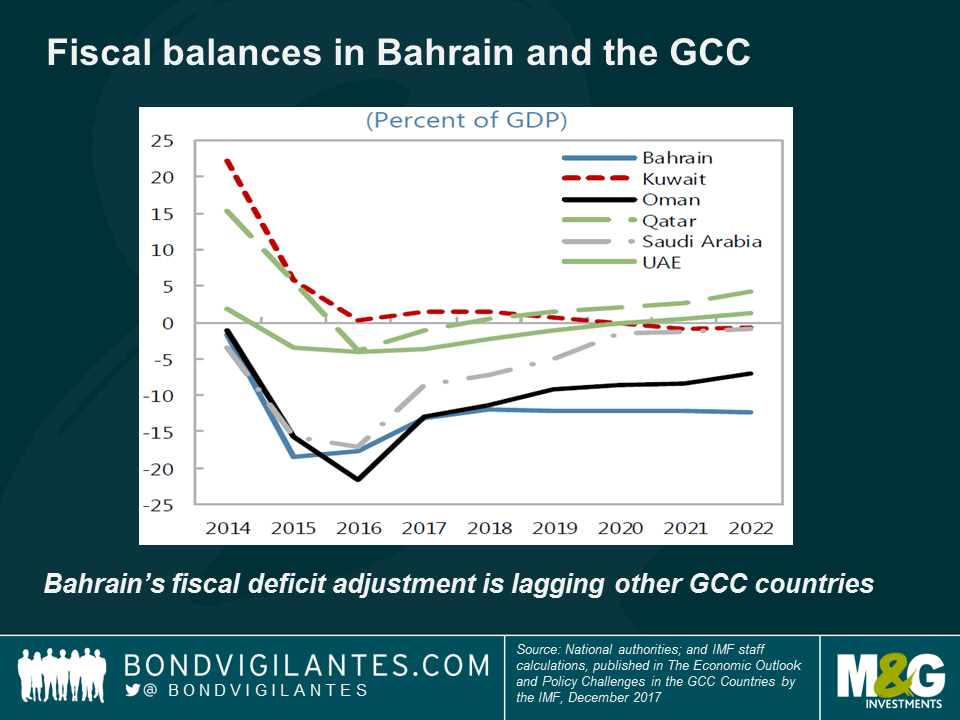

Why are markets starting to worry about a Bahrain default? Debt has doubled in just 3 years, to over 90% of GDP, as the decline in oil prices negatively impacted the fiscal position of the oil exporters in the Middle East. Unlike, most of its neighbours, however, the fiscal adjustment required (i.e. reducing some expenditures such as subsidies and benefits or broadening or increasing non-oil taxes, including VAT) has been very slow.

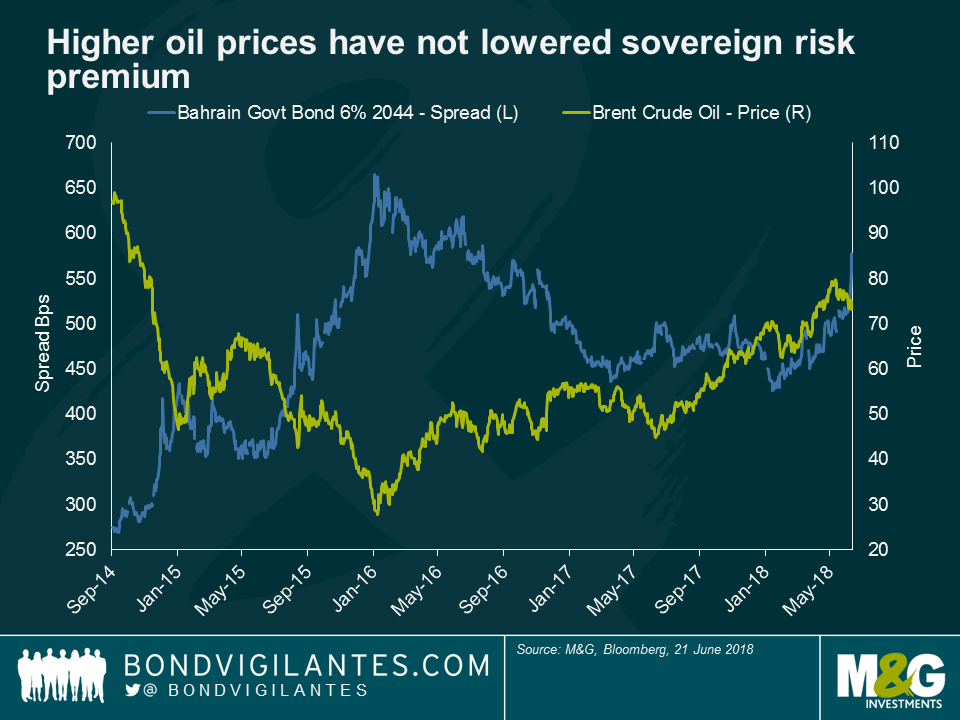

Given a large debt stock and a sizeable fiscal deficit (flow), it appears that Bahrain’s debt dynamics will continue to deteriorate, especially if borrowing costs, which have been relatively low thus far reflecting debt that had been issued at lower interest rates a few years ago, increase further. Increasing US rates continue to be transmitted very quickly into Bahrain’s financial sector due to its currency peg and this is not helping either. Even with Brent in the mid-70s, Bahrain’s spreads remain elevated, signalling that for risk premia to decline, either much higher levels of oil prices, an explicit statement by neighbouring countries detailing financial support or an announcement of a large fiscal adjustment by the government is required.

The fact that the security maturing in November is a sukuk adds more uncertainty due to there having been some corporate sukuk defaults in recent years (with the exception of Dana Gas ($700 million, Al Mudarabah) and Golden Belt ($650 million, Al Ijara)) which have been relatively small and limited to a handful of bonds. A Bahrain default, if it were to happen, would be the first sovereign sukuk default, comprising of 4 sukuks and 9 conventional bonds, totalling almost $15 billion. Sovereign conventional bond defaults for larger issuers with numerous bonds and a wide investor base can be complex and its resolution time consuming. The Argentina 2001 default and subsequent legal battle with holdouts took over a decade to resolve. Venezuela and PDVSA bonds were issued under different legal structures, are held by a wide array of investors and will likely take many years to be restructured. Bahrain, incidentally, is not part of the JPM emerging market bond indices as the country is classified as high-income (like Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Kuwait). Oman, however, is part of the indices as it is not considered a high-income country.

Sukuk defaults have additional legal layers of uncertainty versus a conventional bond (for discussions on Sukuk defaults and legal considerations, see here and here). The trust agreement is normally governed by English law, while the underlying lease agreements (the asset-based part of the sukuk) are governed by national law, Bahraini law in the case of its own sukuks. Finally, whether or not the structure is Sharia compliant, is subject to a third interpretation. The rating agencies do not seem to explicitly take into account the legal risks when rating the transactions. One of them, has stated that ‘XXX does not express an opinion on whether the relevant transaction documents are enforceable under any applicable law. However, XXX’s rating on the certificates reflects its belief that XXX would stand behind its obligations. When assigning ratings to the sukuk issuance, XXX does not express an opinion on its compliance with sharia principles.’

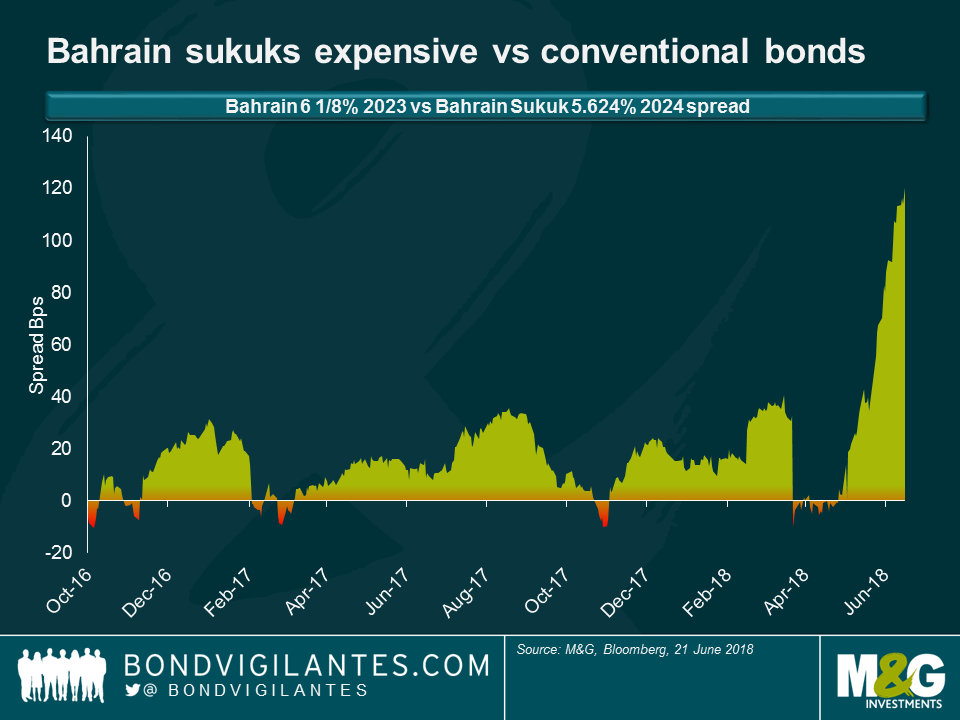

The oddity is that, despite being far more complex from a legal standpoint, spreads on Bahrain sukuks are currently far lower than the spread on its conventional bonds. That is largely because of the strong local support and demands for sukuks vs conventional bonds in recent weeks. Some local investors also cannot sell an instrument below par, as this will require them to account for its market to market loss and may also not be permitted according to Islamic finance. Many international investors have also invested in sukuks, but have the ability to arbitrage between sukuks and conventional bonds as they do not have the same market-to-market considerations or a preference for sharia vs non-sharia compliant instruments.

Given the potential legal complexities should a default occur, not to mention the underlying sovereign credit risk, investors are not being compensated for the risks on Bahrain’s sukuks.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

18 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox