The war of the indices: which inflation measure to use?

After a lengthy review, Britain’s House of Lords has finally said that the inflation index presently used to price inflation-linked securities, train fares or student loans should be replaced. Instead, the Consumer Price Index (CPI) should become the new benchmark, as it includes more items and has an overall higher credibility. So far, so good – except if you are an investor.

The statistics body has acknowledged the limitations of the currently used Retail Price Index (RPI), which has already been de-recognised as an official national statistic, but still, it would rather improve it. In any case, this is not a Lords vs ONS fight, as any change is ultimately in the hands of the Chancellor, who has had this issue on the table for a number of years.

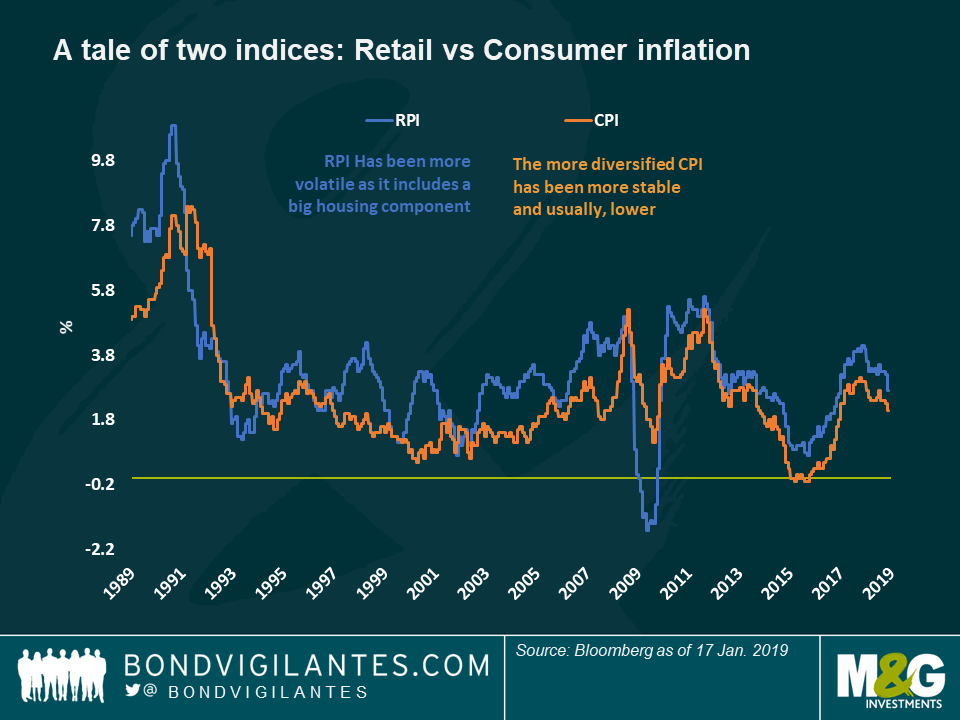

We have discussed the difference between RPI and CPI (known as the “wedge”) many times before, but just as a reminder, RPI is generally higher not only because it is calculated using a different formula, but mainly because it contains a housing component (prices and mortgage interest payments), while CPI does not. Over the long term, and reflecting Britain’s booming housing market, RPI has been around 100 basis points (bps) higher than CPI.

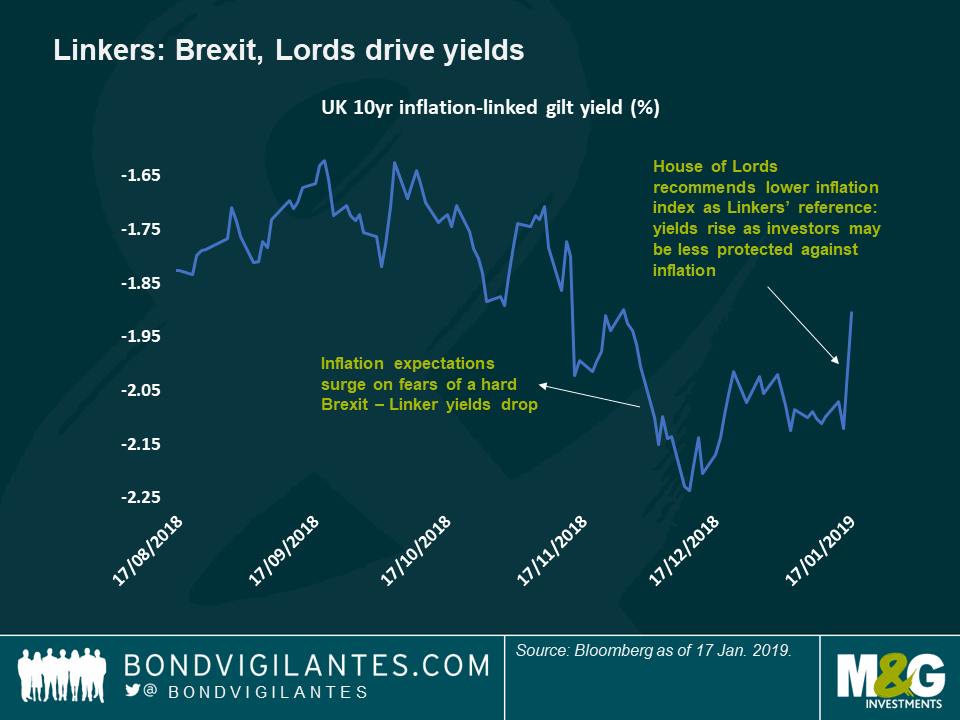

What is the problem with this? For a long time, many have argued that this difference leads to “index shopping,” whereby expenditures gravitate towards the (lower) CPI, while revenues and income generally gain if linked to the higher RPI gauge. Index-linked gilts reference the RPI, the higher number, hence these securities immediately dropped when the upper House delivered its recommendation this week: linker (or inflation-linked bonds) yields spiked to their highest level since November, as seen in the chart below.

The House of Lords said that RPI should correct its 2011 calculation of clothing, a move aimed to reduce the price recognition of some items, but which has led to the opposite. This was an easy and obvious recommendation: was this calculation to change, RPI could fall by 25 bps or, according to some estimates, even 50 bps! All else remaining equal, the tweak would see breakeven rates (used as a proxy for inflation expectations) drop by 25-50 bps, making real yields take the pain (real yields rise as inflation expectations fall). In money terms: a 25-50 bps drop in RPI would see the price of the 2068 linker bond fall by 12% to almost a quarter!

More importantly, the House also recommended that new linker issuance should reference the CPI rather than the RPI. Five years ago, a consultation considered removing the RPI, but the implications of doing so were so severe that the commission in charge decided to stay put. Breakevens soared in relief. If this changes now and linkers end up referencing the CPI, and assuming a wedge of 100 bps, the price of the 2068 linker would almost halve.

Thankfully for investors, big regulatory changes in financial markets tend to be a bit more subtle: it is more likely that the Treasury announces an intention to issue CPI-linked bonds, which could co-exist with RPI-linked ones, while ceasing any new RPI-referenced issuance. This would still take a number of years, as preparations would be needed to prepare the market and to understand the implications. Following the Lords’ review and years of consideration, I am sure that the Chancellor and the Treasury are well aware that a simple switch from RPI to CPI might have a similar effect to the credit events so feared by investors – usually a negative change that diminishes an issuers’ capacity to repay debts. Bondholders would certainly lose – not a good thing for a country with a big current account deficit, something that makes it foreign-capital dependent.

All in all, I can only see rough times ahead as the wedge and CPI-referenced issuance are on the table. However, and in the short term, RPI-linkers might trade higher if issuance is ceased. Still, given the present rich valuations (breakevens are above 3% all along the curve), I expect more focus on the downside from here: if it is true that chances of a hard Brexit have diminished, one could expect a stronger pound limiting inflation growth. Still 12% below its level before 2016’s referendum, sterling has plenty of ground to make up – but that’s another story. Stay with us, I will come back with more comments as events unfold. They surely will.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

17 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox