Could ‘Green Bunds’ be a cure for Europe’s economic malaise?

Compared to one and a half years ago, when the prevailing narrative was still revolving around global synchronised growth, the economic outlook for Europe has darkened significantly. From ‘peak optimism’ levels in late 2017, Euro area real GDP growth has slowed to 1.2%, while Eurozone manufacturing PMI has dropped by more than ten points. Even the notoriously optimistic ECB eventually had to come to terms with reality, slashing their 2019 GDP growth forecast from 1.7% to a dismal 1.1%.

One possible way for Europe’s limping economies to brace themselves against these negative trends and perhaps prevent full-scale ‘Japanification’ would be to suspend austerity and dial up fiscal stimulus to boost economic activity. As Europe’s biggest economy and long-time growth engine, the onus lies first and foremost on Germany, some would argue. And, of course, funding costs would be exceptionally cheap. At current yield levels, Germany would only have to pay around 0.7% in interest when borrowing money for 30 years. Even when taking today’s low inflation expectations with the 30-year euro area breakeven rate at c. 1.4% at face value, funding costs would be negative in real terms. When borrowing over shorter periods, interest rates would be negative even in nominal terms with Bund yields below zero up until nine years to maturity. Investors do actually pay Germany for the privilege of buying the country’s sovereign debt!

Clearly, Germany should seize the moment and issue tons of Bunds, right? A large portion of my fellow German compatriots would vehemently disagree. They’d argue that a balanced federal budget – the proverbial ‘schwarze Null’ (black zero) – and a debt-to-GDP ratio in compliance with the Maastricht criteria of 60% should take priority over boosting the economy via fiscal expansion. There are valid reasons for this position, of course, above all financial stability in the euro area: If Germany abandoned austerity and went on a debt-fuelled spending spree, it would be politically difficult, if not impossible, to demand fiscal discipline of other euro area countries. This would increase the risk of another eurozone debt crisis, followed by expensive bailouts and ultimately debt mutualisation or monetisation.

However, I believe that there is more to Germany’s fervent debt aversion. Without wanting to indulge myself too much in kitchen sink psychology, for many Germans the issue of national debt seems to raise deep ethical concerns, perhaps amplified by the close proximity of the German words ‘Schulden’ (debt) and ‘Schuld’ (guilt). It’s a widely held belief that a responsible government ought to live within its means. Issuing debt is often regarded as unscrupulously borrowing money from future generations, irrespective of attractive funding costs or use of proceeds.

But if the German disdain towards debt-financing originates at least in part from ethical concerns and worries about long-term sustainability, then green bonds – or rather ‘Green Bunds’ – may be the answer. Green bonds are debt instruments that are issued to provide funds for designated environmentally-friendly purposes. For example, Spanish telecommunications provider Telefónica issued a green bond in late January with the intention to use the proceeds of €1 billion for improvements in the company’s energy efficiency by switching from copper to fibre optic networks in Spain.

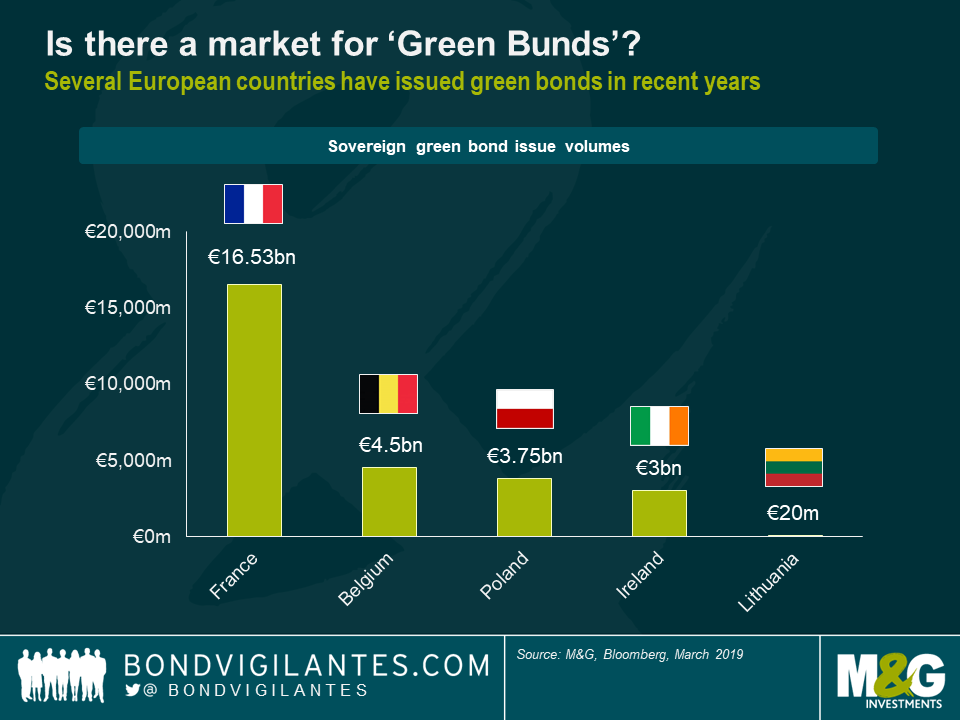

Green bonds are not limited to the corporate sector, of course. In fact, several European countries have issued decent volumes of green bonds in recent years. Belgium, for instance, very recently raised €4.5 billion via a green bond, while France has around €16.5 billion in green bonds outstanding. Poland issued another two green bonds in February, bringing the country’s total green debt to €3.75 billion.

Thus, there seems to be ample investor demand for sovereign green bonds. The market would be deep enough to absorb billions in new issuance. And since green bonds specifically address the issues of ethical finance and long-term sustainability, they might be a suitable vehicle to increase Germany’s willingness to raise debt levels and stimulate economic growth by investing proceeds into environmentally-friendly projects. And various German entities, such as state-owned development bank KfW, have already used green bonds. The next logical step would be the issuance of green German government bonds: Green Bunds.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

18 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox