The fall of the Berlin Wall – a lesson for history or markets?

Earlier this month, Germany celebrated the 30th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, a pivotal moment in recent history that left the Soviet-led communist bloc on the brink of collapse. Whether the Hoff was single-handedly responsible or not, the reunification of communist East Germany with capitalist West Germany was a unique economic shock with a number of potential lessons. Changing demographics, the introduction of a unified currency and tight monetary policy are some of the key changes from this period that have shaped what modern day Germany looks like. While there have clearly been huge strides made by the East since reunification, unrest still exists between the East and West – as Germany is currently facing the threat of another recession, we take a look at whether this gap will close any time soon.

The reunification of a divided population led to over 1 million people taking advantage of their newly found freedom by moving West. Citizens were liberated from a humiliating surveillance state and were free to travel, express opinions and choose their leaders. Today, some East German regions have lower unemployment rates than West post-industrial regions like the Saarland or the Ruhr valley. However, it was not all plain sailing for the East Germans. Having been brought up for four decades in an environment of oppression and indoctrination, many could not suddenly adapt to the rigours of capitalism. As average productivity levels in the East were only 30% of those in the West, estimates suggest that up to 80% of these unproductive Eastern workers found themselves out of work at some point during these transition years as they adjusted to a new regime. 8,500 companies in the East were privatised or liquidated by the Treuhand, a newly founded and highly controversial government agency. Most of the liquidated assets fell into Western or foreign hands, hindering the development of an Eastern capitalist class.

Eventually, the convergence between East and West ground to a halt – today, just 7% of Germany’s most valued 500 companies (and none listed in the DAX30) are headquartered in the East – this starves municipalities of tax revenue and contributes to the East-West productivity gap, which stood at around 20% for 20 years. Labour productivity and levels of industrialisation still lag behind the West – median wages are still 20% lower than in Western states for the same work. Many feel the East is still ‘ruled’ by the West, with East Germans holding barely 4% of elite jobs in the East and many renting flats from Westerners, who own most of the housing stock. Changing demographics also pose a risk, as due to the mass movement of youngsters, the East has an older population than the West. Since 1990, the number of over 60s there has increased by 1.3 million despite the overall population falling by 2.2 million. This demographic decline poses a threat to the productivity of the Eastern working-age population as limited new talent is joining the bottom of the East German career ladder. Despite narrowing since reunification, there is also a risk that the gap between West and East living standards will actually widen going forwards, as although overall emigration to the West is slowing, Eastern cities are now sucking up the educated workers from struggling small towns and villages.

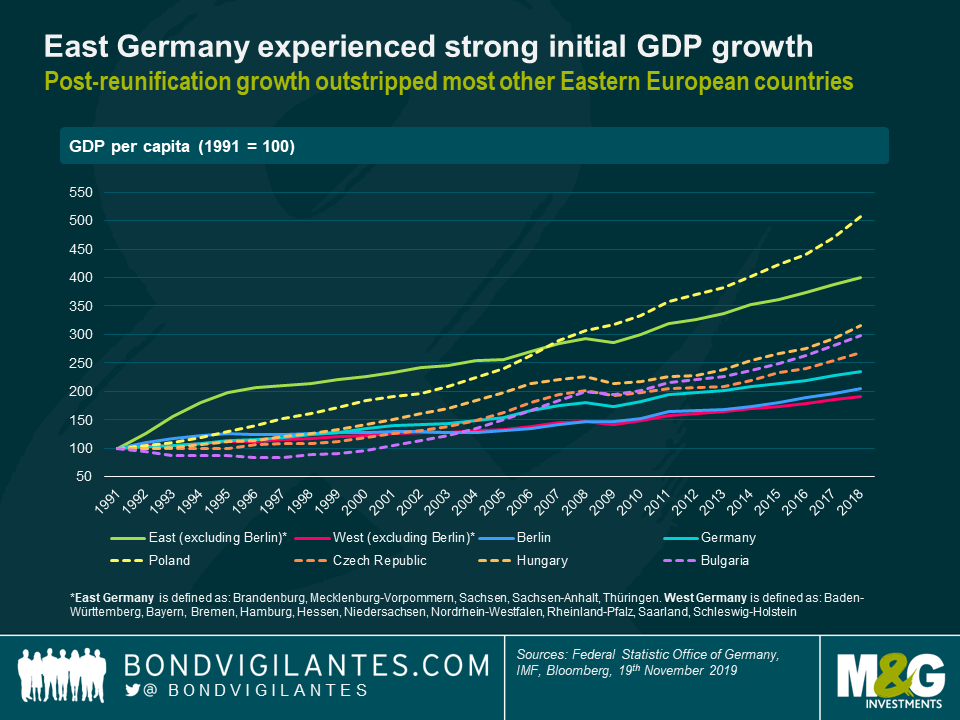

These trends can be observed in terms of economic growth on a national level, where East Germany experienced strong, non-inflationary GDP growth during the early 1990s after reunification initially spurred demand in the region. West Germany however, seems to have experienced very little growth in GDP per capita throughout the early 90s, despite initially coping rather smoothly with the strains that unification put on its resources. Germany as a whole experienced sluggish growth in the 90s, which many attribute to the drastic deterioration in Germany’s public finances post reunification. However, it is unclear whether West Germany’s growth slowed due to an influx of unproductive workers from East Germany (where the Eastern economy was only 10% the size of Western GDP), or by poorly timed tight fiscal and monetary policies causing a protracted deflationary economic environment. Nonetheless, despite regional differences and poor overall growth, East Germany still fared better than most other Eastern European countries that shook off communism over the 90s. A glance around the rest of the former Eastern Bloc, where unemployment and poverty tend to be higher, suggests that East Germany was lucky to have had a strong Western state to support its transition to a market economy. The application of Western laws and practices arguably saw off the threat of oligarchic corruption that has plagued many of Germany’s Eastern neighbours, where Poland seems to be the key exception.

Today, these regional inequalities persist and with Germany facing the threat of another recession, it does not seem likely that the gap between East & West will close any time soon – as it stands, the constitutional pledge of “equivalent living conditions” across Germany is looking increasingly unattainable.

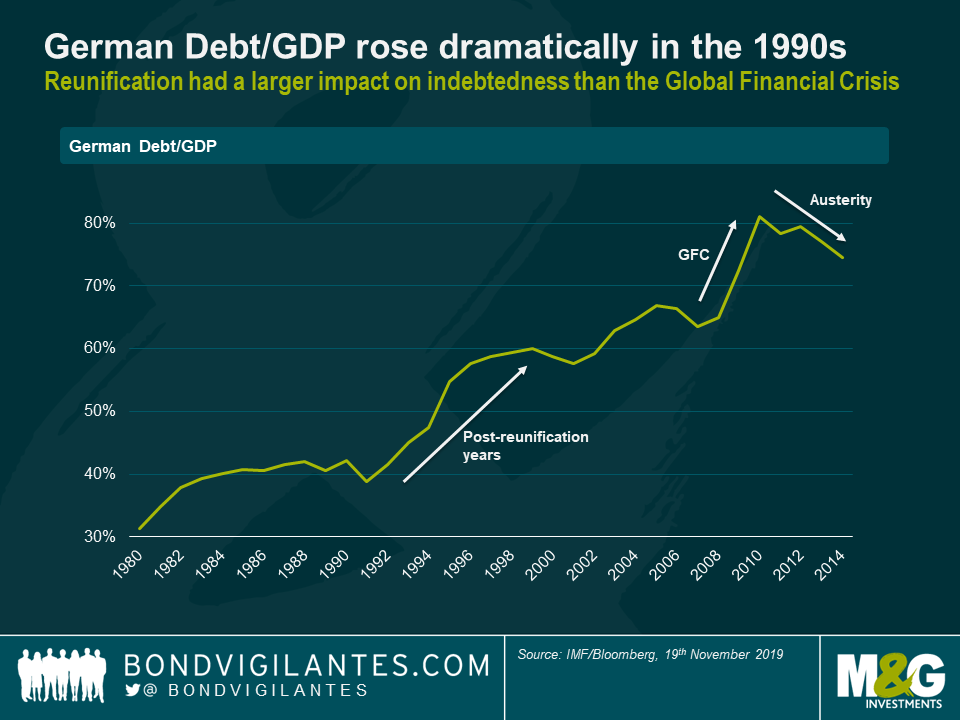

What happened to bond yields post reunification? The Bundesbank attributed almost all of the rise in public debt/GDP since 1989 to the costs of unification.

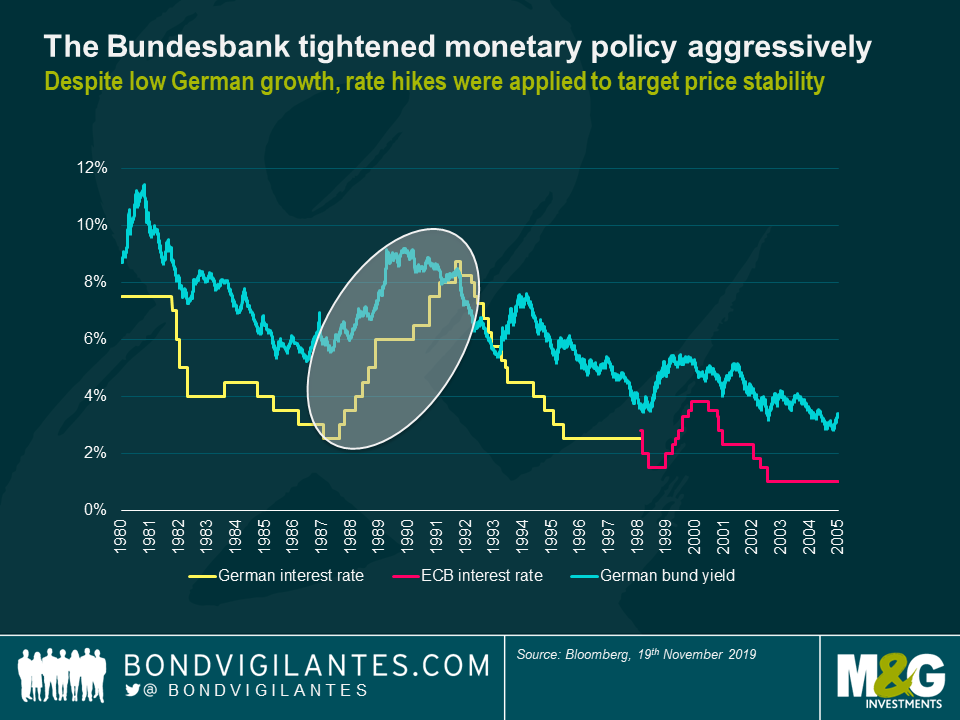

The German central bank thought a key risk for German fixed income markets was that the high speed of reunification could lead to a public sector deficit and thus destabilise inflation and undermine faith in the Deutschmark, the anchor of the European Monetary System. The Bundesbank thus tightened monetary policy aggressively, pushing up German rates by about 3% over 1991 and 1992. As significant increases in taxes and administered prices pushed up inflation, the Bundesbank further hiked rates. Unfortunately, the central bank’s aggressive pursuit of price stability meant German society paid a steep price in terms of high unemployment and continual low economic growth. This stance saw the last real jump in Bund yields that markets have seen since 1989 as the interest burden soared, despite the impact on government bond yields one would normally associate with lower growth rates. The high German rates made it difficult for other European economies to pursue corrective monetary policy actions. The outcome would be the crisis of the ERM in 1992 and 1993. Since then, continual monetary loosening and a ‘flight to safety’ mentality from debt-ridden peripheral European economies have led to investors piling in to Bunds and driving yields into current negative territory.

As part of reunification, there were huge transfer payments (nearly €2 trillion) from West to East. The West German chancellor (Helmut Kohl) converted savings into hard currency at the generous exchange rate of one Deutschmark to one Ostmark. Thus, unlike any other country ever freed from oppression, the entire population of East Germany was given citizenship of a big, rich democracy. The Deutschmark saw increased demand, especially from abroad, as it quickly became a substitute for the Dollar. Despite weak economic growth in the 90s, the Bundesbank’s strict monetary discipline applied to the Deutschmark meant it retained much of its strength as a safe haven currency (before Germany adopted the physical Euro in 2001). However, Germans now seem to be rethinking the concept of sudden internal transfers – perhaps the unified country should have developed a new constitution rather than extend the hand one-way, or perhaps a special economic zone in the East should have been formed, allowing for gradual convergence rather than sudden reunification. Many Westerners feel that investment in the East was made at the expense of investment in other struggling regions, especially as aid measures were initially meant to be temporary. Increasingly, there’s a call for a rethink of fiscal equalization in place of the almost $70 billion a year that has flowed into the former East Germany since 1990.

Subsequently, what are the key lessons that we can draw from these years? Germany’s recent history teaches us that even in a near perfect model, currency integration is difficult. Implementing a unified currency means that struggling economies can no longer use a lower exchange rate to boost exports and thus they remain uncompetitive. The currency union in Germany meant that East German firms suddenly had to compete with Western firms at a similar level of prices, wages and costs, despite a much lower level of productivity. Industrial output dropped by 35% in the first month and fell by another 15% in the next month. This basic flaw of a single currency can be seen through the struggles of member economies in the Eurozone, particularly peripherals, where once economies begin to diverge from one another, a common currency and monetary policy can cause the divergence to increase. In terms of lessons for bond markets, Bunds are a reasonably unique case as typically government bond yields follow weak nominal GDP growth. However, during reunification yields jumped around 150 basis points despite weak German growth. Since then, Bund yields have fallen due to a combination of weak growth and investors in peripheral economies piling into Bunds during times of uncertainty.

To conclude, Germany is a reminder of the importance of history and path dependency. Going forward, the differences in East Germany’s cultural and institutional background compared to the West are still evident in the lives of German citizens today. Discontent is still prevalent on both sides of the now-crumbled wall, and 30 years on, East Germany is still waiting for the economic upswing that the currency union was designed to trigger.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

18 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox