Craics begin to show in Ireland’s political establishment

With European media outlets focusing on the coronavirus and storm Ciara this week, only little attention was given to the Irish general election held on Saturday. Undeservedly so, I’d argue, considering that the election results mark a seismic shift in Irish politics. The surge of Sinn Féin, winning 24.5% of the first-preference vote, de facto ended the two-party dominance of Fine Gael (20.9%) and Fianna Fáil (22.2%) — a constant in Irish politics since the country gained independence nearly a hundred years ago.

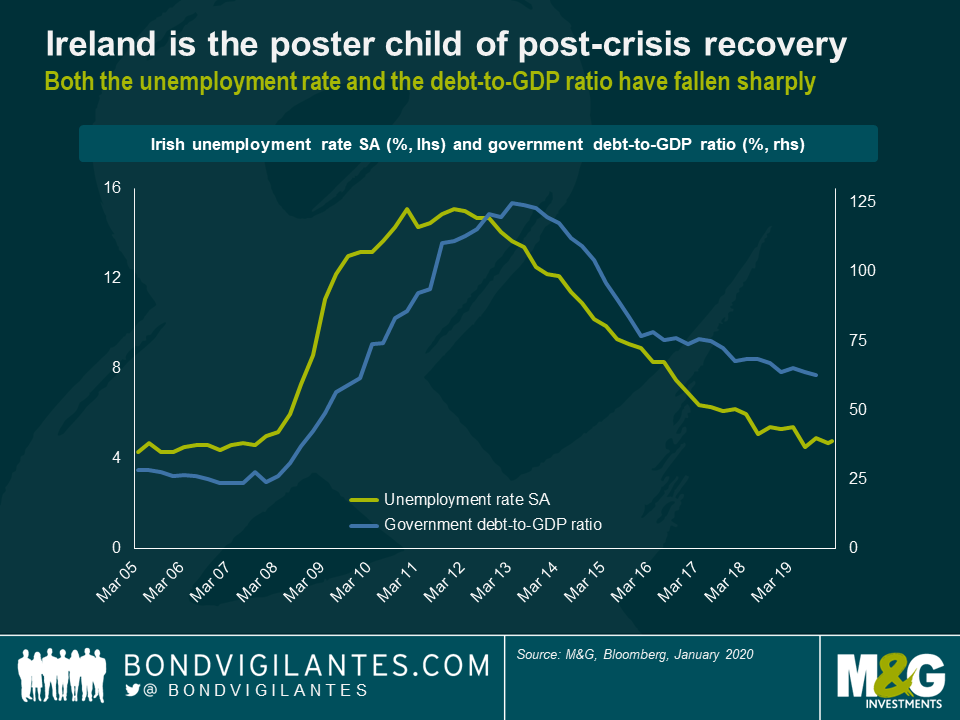

At first glance, the strong shift of votes towards Sinn Féin, who had positioned themselves as a left-wing anti-establishment party in the runup to the election, seems rather counterintuitive. Judging by most economic metrics, the recovery of Ireland after the European debt crisis has been a truly remarkable success story. For instance, the Irish unemployment rate, which had peaked at around 15% in 2021/12, has fallen by two thirds and is now below 5%. The government debt-to-GDP ratio has roughly halved from its 2013 peak (c. 125%) to currently c. 63%, which is in striking distance to the 60% debt limit specified in the Maastricht Treaty. Consequently, funding conditions have improved dramatically for Ireland. At the height of the debt crisis in 2011, the yield of 10yr Irish government bonds shot up to a whopping 14%, forcing Ireland to accept bailout loans. In contrast, the current Irish 10yr yield is c. -0.1% — pretty much in line with the French 10yr yield — which illustrates how profoundly market perceptions on Ireland have improved in recent years.

But why did Irish voters decide to shake up the political status quo when mainstream politics had helped produce such impressive results? Sinn Féin’s unwavering pursuit of an all-Ireland agenda sets them apart from their more moderate political rivals Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil. An exit poll taken at the Irish election on Saturday suggests that a significant percentage of the electorate (57%) are in support of referendums on Irish unity north and south of the border within the next five years — a key political goal of Sinn Féin.

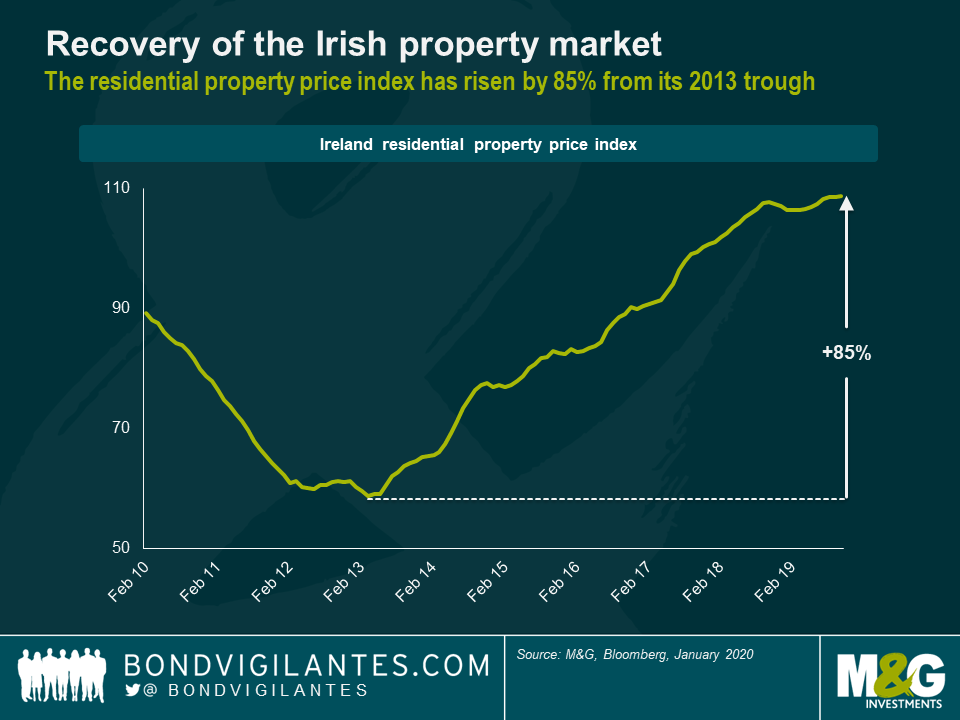

Although the question of Irish unity may have been a factor for some in the election, there were other factors cited as being more important that unity at play as well. When voters were asked in exit polls on Saturday what was most important to them in deciding how to vote, social issues — namely healthcare and housing — were topping the list. While the Irish economy as a whole has recovered superbly from the grave dislocations caused by the European debt crisis, it seems a significant proportion of the Irish people feel rather left behind. For instance, the Irish residential property price index has risen by c. 85% from its 2013 trough, which is great news for Irish home owners, of course. But, on the flipside, it has become a lot harder for young people and low-income families to get on the proverbial property ladder. Hence, Sinn Féin’s promise to build 100,000 new social and affordable homes, in addition to other left-wing policies, fell on sympathetic ears.

Since social issues seem to have played a crucial role the Irish election, it is worth comparing Ireland to other European countries with regards to key societal metrics. The Gini coefficient, for instance, is a statistical measure of dispersion and is typically applied to quantify the level of income inequality within a population. Lower values indicate lower levels of inequality, and vice versa. Interestingly, Ireland ranks close to the bottom of the Gini range within its European peer group. Sure, the usual suspects (e.g., Norway or the Netherlands) exhibit even lower Gini coefficients. But the level of income inequality in Ireland is significantly below EU average, lower than in Germany, Spain, Italy, Greece or the UK. The picture is slightly less benign for Ireland when it comes to the percentage of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion, another important social indicator. Ireland appears to be a halfway house between core European countries (Germany, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, etc.) with values below 20% and southern periphery countries, such as Spain and Italy, with values beyond 25%. That being said, it’s worth pointing out that Ireland’s poverty risk figure is still below EU average.

So, what lessons can we learn? Frankly, I think it is pretty remarkable that in a country like Ireland, which has been highly successful over many years based on most economic metrics, a left-wing anti-establishment party can swoop up nearly a quarter of votes in a general election. It serves as a stark reminder that even seemingly stable political landscapes can easily erode, when large parts of the population feel that they have been excluded from the spoils of economic growth. Even though Ireland’s Gini coefficient and poverty risk are not flashing red by any stretch of the imagination, social issues, such as housing or healthcare, were very much on people’s minds. These topics are all too familiar in most other European countries and we should thus expect anti-establishment movements challenging the status quo to gain political momentum elsewhere as well. And, just to be clear, within democratic systems these election results are a perfectly legitimate expression of the will of the people.

But there are certain risks attached, of course. When political constellations become more complex, it can become rather difficult to form stable governments. As a reminder, it took Germans half a year to forge a new government after the last federal election. This sluggishness, which affects consensus building and decision-making in fragmented parliament more broadly, can be costly especially when acute crises arise that demand an immediate response. For investors like ourselves, proper assessment of political risk becomes more relevant as election results get less predictable. We shouldn’t be lured into a false sense of security by long-standing political orders but factor in fragility and the expected market volatility that goes along with it.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

18 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox