ECB to the rescue: Whatever it takes 2.0 ahead?

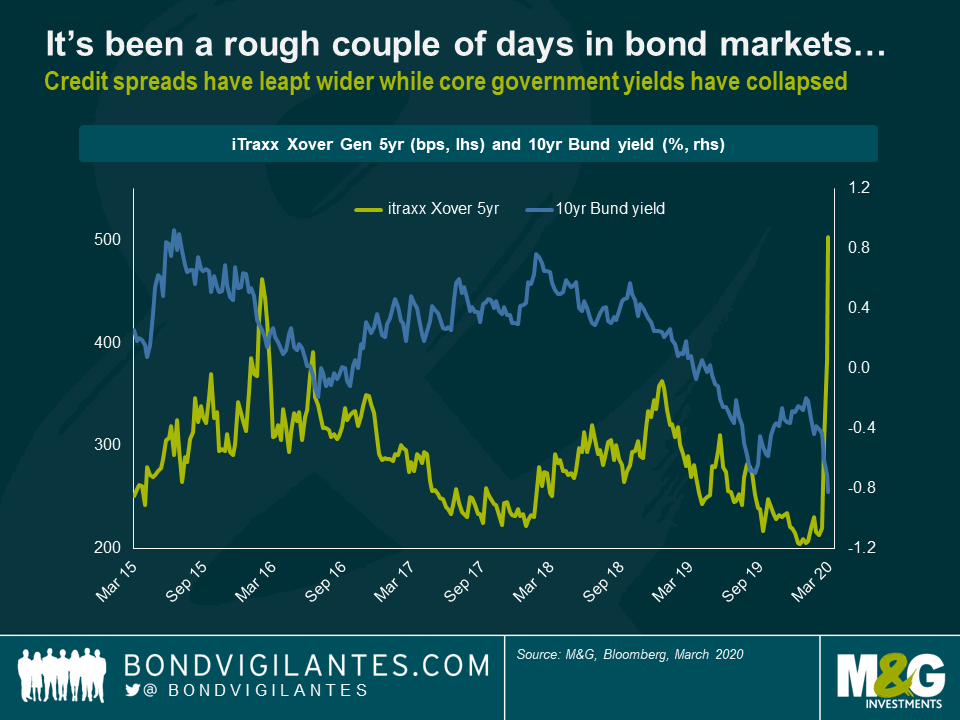

It’s been a rough two weeks in bond markets, to say the very least. Risk-off sentiment is reigning supreme. In Europe, looking at my screens this morning, iTraxx Xover—a bellwether of European high yield credit risk—jumped to its widest level since mid-2013, while the yield on 10yr German Bunds dropped to an all-time low below -0.8%.

In previous times of market turmoil, the European Central Bank (ECB) has stepped in to signal more monetary stimulus. In March 2016, after a horrendous couple of months for risk assets, the ECB announced it would ramp up its quantitative easing programme by adding corporate bonds to the shopping list. Even more dramatically, former ECB President Mario Draghi’s famous “whatever it takes” speech in July 2012 is largely recognised as one of the key factors putting an end to the European debt crisis. Considering the recent worsening of the COVID-19 situation and subsequent market reactions, all eyes are now on Christine Lagarde and her comments after the ECB’s Governing Council meeting on Thursday. In my view, essentially three options are available to the ECB this week: business as usual, measured response or big bazooka.

Option #1: Business as usual

In this scenario, the ECB simply acknowledges the heightened risks for the economic outlook and medium-term inflation in the euro area caused by COVID-19, but refrains from altering its monetary policy stance, which is already highly accommodative. The main deposit rate is kept at -0.5% and net purchase volumes under the Asset Purchase Programme (APP) continue to run at a monthly rate of €20 billion. The rationale here would be that monetary policy alone won’t be enough and that the onus is first and foremost on governments and fiscal easing. Rushing into monetary emergency measures prematurely might actually be counter-productive. The ECB switching into full-on alarmist mode could very well spook markets further. Also, considering that the ECB’s deposit rate is already deeply negative, which limits the scope of further rate cuts compared to other central banks, the ECB might conclude that it is sensible at this point to keep as much dry powder as possible to be able to act decisively later, in case the COVID-19 situation continues to worsen.

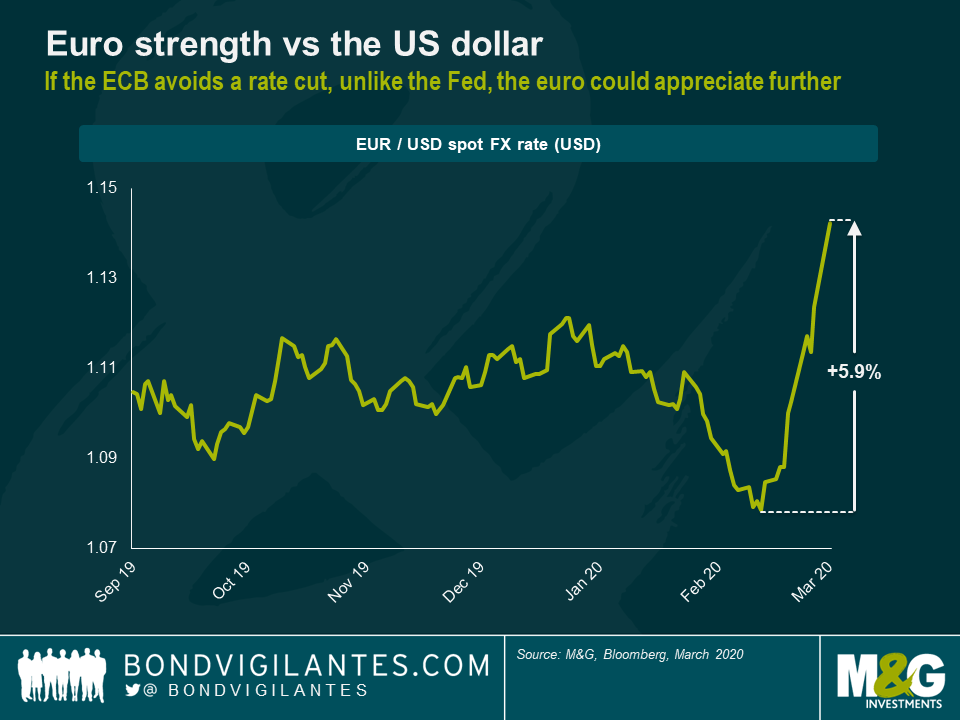

Although there may be valid reasons supporting a “business as usual” approach, I don’t think it is a likely scenario. First, expectations amongst market participants are high with regards to further monetary stimulus from the ECB. At the time of writing, the implied probability of an interest rate cut on Thursday, using overnight index swaps, is close to 100%. The ECB is under no obligation whatsoever to satisfy market expectations, of course. But avoiding the highly anticipated rate cut might fuel further turbulences in financial markets, something the ECB would rather like to prevent. Second, in a world in which other central banks—e.g. the Fed, the Bank of Australia, the Bank of Canada—have decided to cut rates in response to COVID-19, the ECB could quickly become “the odd one out” by keeping rates steady, which would put further upward pressure on the euro. The currency has already appreciated by around nearly 6% against the US dollar since mid-February. Continued strengthening of the euro would be yet another head-wind for export-driven European companies—and by extension, the eurozone economy as a whole—already suffering from weakening demand and supply chain disruption caused by COVID-19. To be clear, the ECB’s mandate does not involve actively managing the strength of the euro in the FX market. But putting an end to the recent euro rally would at least be a desirable side-effect of a rate cut, albeit not the main reason behind it, and might help in moving European inflation closer to its target through rising import prices.

In an attempt to calm markets, with the additional benefit of dampening the strength of the euro, the ECB is going to take action on Thursday, I believe. If so, the key question is of course how far will the ECB go? This leaves us with options #2 and #3.

Option #2: Measured response

In this scenario, the ECB cuts interest rates by a modest amount, say 10 basis points (bps). This would bring the main deposit rate to a new record low of -0.6%. Simultaneously, monthly net asset purchases are increased to perhaps €60 billion or even €80 billion a month. This would be a tripling or quadrupling in purchase volumes, respectively, from the current level of €20 billion, but it wouldn’t be unchartered territory. The ECB used to run its APP in the past at €60 billion (March 2015 to March 2016 and April to December 2017) and €80 billion a month (April 2016 to March 2017).

I’d say this is perhaps the most likely scenario, but arguably the least desirable one. The danger is that the ECB would get the worst of both worlds. Moderate policy action by the ECB, if not accompanied by substantial fiscal stimulus, is unlikely going to be enough to instil lasting confidence into markets that just shrugged off a 50 bps cut from the Fed. The risk-off sentiment could easily escalate further into a fully-fledged market crisis. Simultaneously, the ECB would have depleted some of its dry powder, thus limiting the scope of any additional emergency policy actions that might be necessary in the future if the adverse economic impact of the COVID-19 outbreak exceeds current projections.

Option #3: Big bazooka

The idea here be to create another “whatever it takes” moment that immediately helps calm down markets and avoid a full-blown panic amongst investors that, if left unchecked, might compromise the stability of the financial system and ultimately threaten the real economy. In this scenario, the ECB acts boldly both in terms of interest rates and asset purchases. Rates are cut by at least 25 bps, which would bring the ECB’s deposit rate to -0.75% and thus in line with the policy rate of the Swiss National Bank. In addition, APP purchase volumes are increased beyond €80 billion a month, perhaps to €100 billion. Importantly, in order to signal to market participants that the ECB still has more firepower to further upscale asset purchases in the future if necessary, certain changes to the APP rules might need to be implemented.

- Under the rules of Public Sector Purchase Programme (PSPP) within the APP, government bond purchases are guided by the ECB capital key. Due to the combination of Germany’s high capital key weight and relatively low level of indebtedness—Germany ended 2019 with a record budget surplus of €13.5 billion after all—Bunds have become a bottleneck in the programme. In order to create headroom in a meaningful way, the capital key rule could temporarily be suspended, thus allowing the ECB to tilt purchases more heavily towards Italian BTPs, of which there are plenty. Politically this step would be highly controversial, of course. But given that at the moment Italy is more severely impacted by the COVID-19 outbreak than any other European country, the rule change seems at least justifiable. If the ECB ever wants to suspend the capital key, now is the time.

- The rules of the Corporate Sector Purchase Programme (CSPP) within the APP do not allow for the purchase of bonds issued by banks. Since bank bonds account for around 30%, give or take, of the European investment grade corporate bond universe, their inclusion into the CSPP would help increase capacity considerably. It would also serve another purpose. Banks’ profitability would suffer from the deep rate cut in the bazooka scenario. Generating CSPP demand for bank bonds, thus effectively lowering funding costs, would help soften the blow to the European banking system.

As compelling as it may seem to take out the big bazooka, it is a high-risk strategy. If it works and a veritable crisis—both in markets and within the real economy—can be averted through decisive ECB action early on, Christine Lagarde would reach immediate superstardom amongst central bankers. However, if not flanked by fiscal easing in a concerted fashion, the bazooka approach could also easily backfire. If the measures fall flat, markets continue to tumble and the transmission of monetary stimulus into the real economy fails, there wouldn’t be an awful lot more the ECB could do going forward. And markets would know that the ECB—and other central banks—are at their wits’ end.

In summary, Christine Lagarde is not to be envied this week as the ECB is caught between a rock and a hard place. Inaction or any half-hearted measures might lead to further deterioration in market stability that could soon spiral into a full-blown crisis, affecting both financial markets and the real economy. But going “all in” now in an effort to stimulate the economy and turn around investor sentiment before things escalate any further carries the risk of being left without any room for manoeuvre later. For investors, navigating markets is going to be a tricky exercise. Given that there isn’t any obvious path to take for the ECB—or any other central bank for that matter—it is a risky strategy to bet on any particular monetary policy outcome.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

18 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox