How to get re-elected during a pandemic – lessons from CEE/CIS

The coronavirus crisis is having a profound and lasting effect on the global economy, with the vast majority of countries expected to get back to their 2019 level of economic output only in 2022. The consequences of the crisis are not just limited to the economy and to changes in human behaviour. In many countries of the CEE/CIS region, the crisis has coincided with election cycles and will lead to significant changes in political landscapes over the years to come.

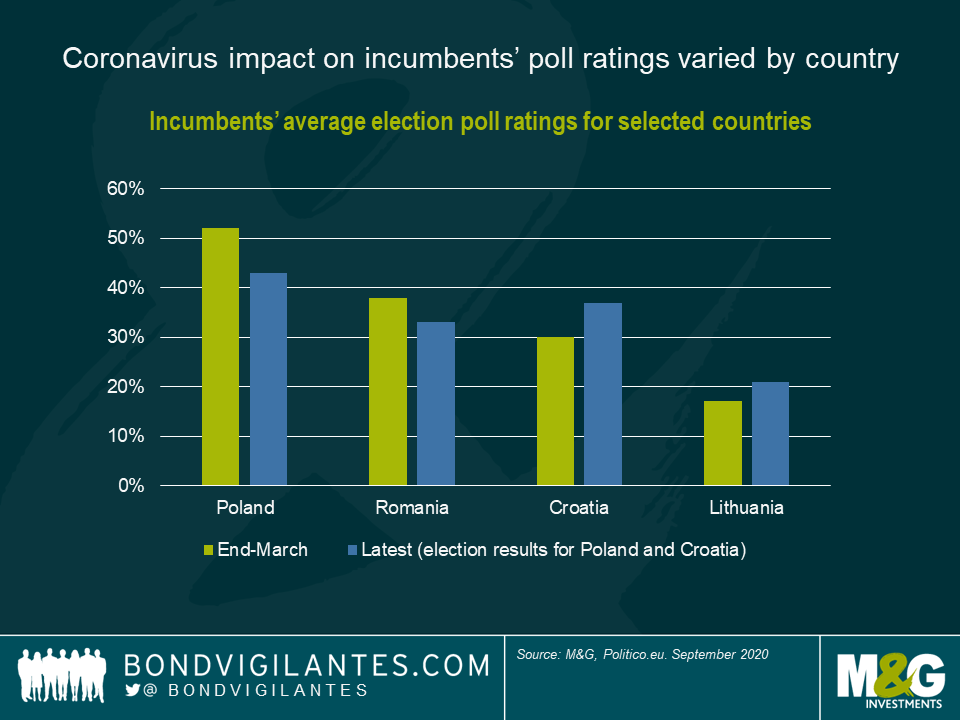

Naturally, this crisis has presented a significant challenge for incumbent governments and presidents trying to maintain their popular support levels. Election date shifts due to the epidemiological situation only added to complications in some countries. During a crisis of this scale and uncertainty, some policy mistakes were perhaps unavoidable. As a result, in many countries people have blamed the authorities for their economic and social troubles, even with the huge fiscal and monetary support packages provided. Consequently, what seemed before the crisis to be an easy road to victory for the incumbents has turned out to be quite the opposite in some cases. For example, in Poland’s July elections the incumbent president Duda managed to defeat his main opponent only in the second round with a minimal lead (51% vs 49%), despite consistently polling at least 20 percentage points above his main opponent up until late May. In North Macedonia too, the ruling party barely managed to secure a win, and at certain cost: to obtain a coalition majority of just a few seats in parliament, they had to agree to a transfer of the prime ministerial post to an Albanian minority party at least three months before the next parliamentary elections.

Interestingly, the crisis has not led to the falling popularity of the incumbent government everywhere – in some cases quite the contrary. For example, in Lithuania a robust policy response to the health crisis (resulting in one of the lowest number of cases per population in Europe) helped the ruling party to improve its position in the polls ahead of parliamentary elections in October. Some other governments tried to capitalise on providing generous fiscal support (including direct cash payments to the people) by holding elections shortly afterwards, while the epidemiological situation was still relatively benign following the initial strict lockdowns. In particular, this cunning strategy was successfully implemented in Serbia and Croatia. In Serbia, the ruling coalition was able to strengthen its parliamentary majority significantly compared to the previous elections, scoring more than 70% of the vote. To be fair, this result was also made possible by very impressive economic achievements in previous years, as well as some opposition parties having decided to boycott the election.

In Croatia, the ruling party also managed to improve its popularity shortly before the vote, resulting in a stable coalition government instead of the unstable populist-led coalition predicted by many experts. Conveniently, the election was held before the main tourist season began, which subsequently led to a significant spike in coronavirus cases and painful economic losses from a slump in foreign tourist arrivals. The importance of this factor for popular support was vividly demonstrated later in Montenegro, another country with a huge dependence on tourism. In contrast to Croatia, the ruling party did not manage to engineer early parliamentary elections before the tourist season, and its choice to hold them in late August proved to be unfavourable. After declaring itself completely virus-free in May, Montenegro has experienced a second wave of the virus since late July and partial lockdown measures were re-introduced. While economic problems accumulated in previous years have also played a role, this was perhaps the decisive factor causing the ruling party narrowly to lose the election to a united opposition for the first time in 30(!) years. Tourism impact could also prove crucial in Georgia, which will hold its parliamentary elections in October. According to the World Travel and Tourism Council, the direct and indirect contribution of tourism amounts to a huge 34% of GDP in Georgia (compared to “only” 22% in Montenegro and 25% in Croatia). This places the country among the most exposed in the region and the opposition is clearly trying to capitalise on the significant loss of tourist revenues due to the crisis.

Perhaps the most well-publicised example of coronavirus impacting the political landscape significantly is Belarus. The local authorities decided not to impose any lockdown at all in response to the crisis. In fact, Belarus was the only country in Europe continuously running its football championship (with spectators allowed in the stadiums), while president Lukashenko even called coronavirus a “psychosis”. This strategy somewhat limited economic losses at first, but resulted in a high number of cases per capita, and ultimately backfired when Belarus failed to receive any crisis-related financial support from the IMF. While the IMF readily deployed funds without any conditions to all countries in need (even to those without a realistic possibility of a near-term IMF programme), it was reluctant to support a country which did not introduce any significant health and safety measures. What is more, parts of the ruling elite as well as ordinary people in Belarus were also seemingly upset with the government’s handling of the crisis, which added to previous years of weak economic growth. This contributed to a somewhat unexpected and rapid heating up in politics just a couple of months ahead of the presidential elections in August. After what has been deemed by most observers to be the falsified victory of the incumbent, large scale protests are continuing in Belarus now. This may ultimately result in the ousting of president Lukashenko, who has been in power since 1994.

The Belarus situation is clearly a warning to another long-standing leader in the region facing re-election this year – president Rakhmon has governed Tajikistan since 1992. Tajikistan remains one of the poorest countries in the world with very weak institutions (including its healthcare system) and high public debt levels. In contrast to Belarus though, the government was prudent enough to engage quickly with the IMF and receive some emergency crisis-related funding. While the chances of any political change this October are very slim, the example of Belarus shows that people’s needs cannot be fully ignored in times of crisis, even in autocratic regimes.

Considering potential economic consequences, arguably the most crucial election in the region this year will take place in Romania in December. Significant deterioration in fiscal deficit and public debt levels in recent years put Romania on the brink of losing its long-held investment grade status. Since March, support levels for the current market-friendly government fell as it tried to juggle between the necessity to provide large, crisis-driven fiscal stimulus and the equally urgent need for fiscal consolidation. So far the government has narrowly survived the no-confidence votes in parliament, but the upcoming election will be the true test of its viability in the medium term. All three main rating agencies currently have negative outlooks on Romania’s BBB- credit rating, and it is uncertain whether they will even have the patience to wait until December in a hope of swift post-election policy reversal.

One of the most important elections for the region (and perhaps for EM as a whole) this year will actually take place outside it. In November, the US will choose its president. The handling of the coronavirus outbreak is clearly undermining Trump’s support levels, and the long-term implications for the region in the case of a Biden victory could be significant. While a possible reduction of US protectionism and trade war rhetoric could be positive for the global economy and EM, the implications for particular countries could differ. In particular, a Biden administration might step up sanctions pressure on some countries like Russia and Turkey in response to their human rights violations and military interventions. Many observers perceive it is likely to adopt a more structured approach to foreign policy, in place of the “deal-making” attempts (largely based on personal relationships with foreign leaders) favoured by president Trump.

In any case it is clear that, like its economic effects, coronavirus-related political volatility is unlikely to end in 2020. Arguably, 2021 may prove to be an even more difficult year for incumbent authorities facing re-election, particularly as they are likely to be running out of policy responses and resources to mitigate the negative impacts of the crisis. Unless healthcare and economic situations improve markedly, people across the world might start losing trust even in the most popular governments and presidents.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

18 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox