Five reasons why Mark Carney might be short of options when he becomes BoE Governor in July

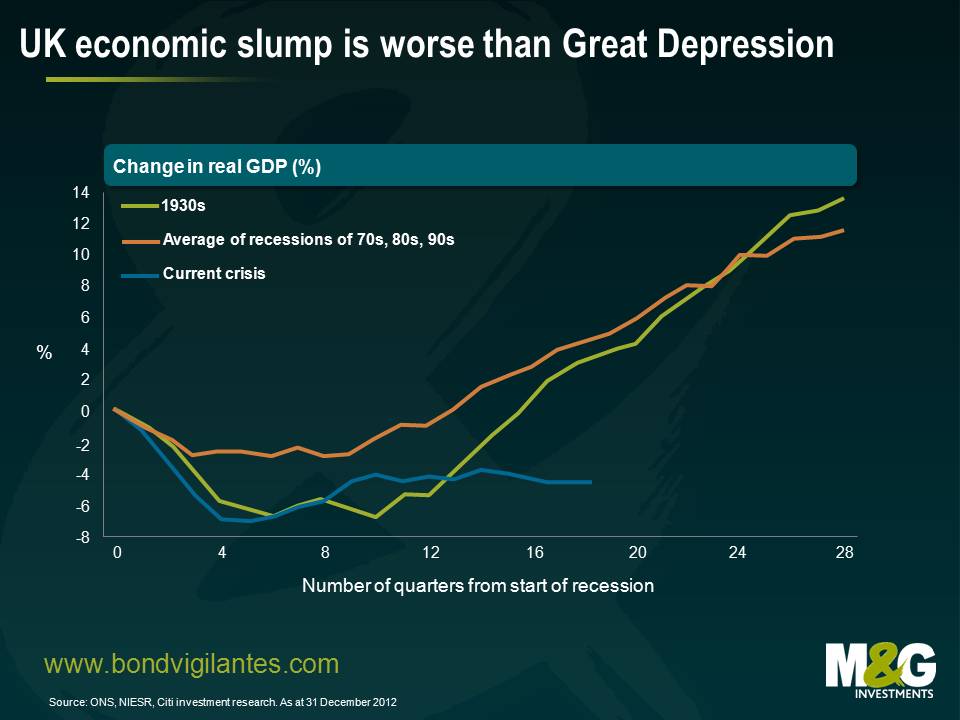

Mark Carney, currently Canadian central bank governor, will become the Governor of the Bank of England at the start of July. Handpicked from outside of the official application process by Chancellor George Osborne, he comes with high expectations about what he can do to get the UK economy out of a downturn arguably more severe in GDP terms than was seen during the Great Depression (or The Slump as it was known here). This now famous chart from the NIESR shows the extent of the underperformance of the economy relative to past recessions.

Carney’s stock is high – whilst the UK and the Eurozone remain in, or around, recessions, Canadian GDP is growing at 1.7% year on year, and its growth has outperformed the US economy both during and post the financial crisis. Inflation in Canada has averaged 1.8% over the past 6 years, compared with 3.1% CPI in the UK – perhaps the real blemish on inflation puritan Mervyn King’s legacy.

With Osborne having ruled out fiscal policy as a tool to get the UK out of its current Slump, our hopes now rest on either a significant and speedy recovery of our biggest trading partner, the Eurozone economy (and that looks to be going in the wrong direction), or monetary policy. In other words do the government’s hopes all rest on Carney doing something new and different, or massively increasing the scale of what the Bank of England has done before? If so we might all be disappointed. Here are five reasons why Mark Carney’s degrees of freedom might be fewer than he, and we, had hoped…

1 You can’t cut bank rate in the UK because you hit the building societies.

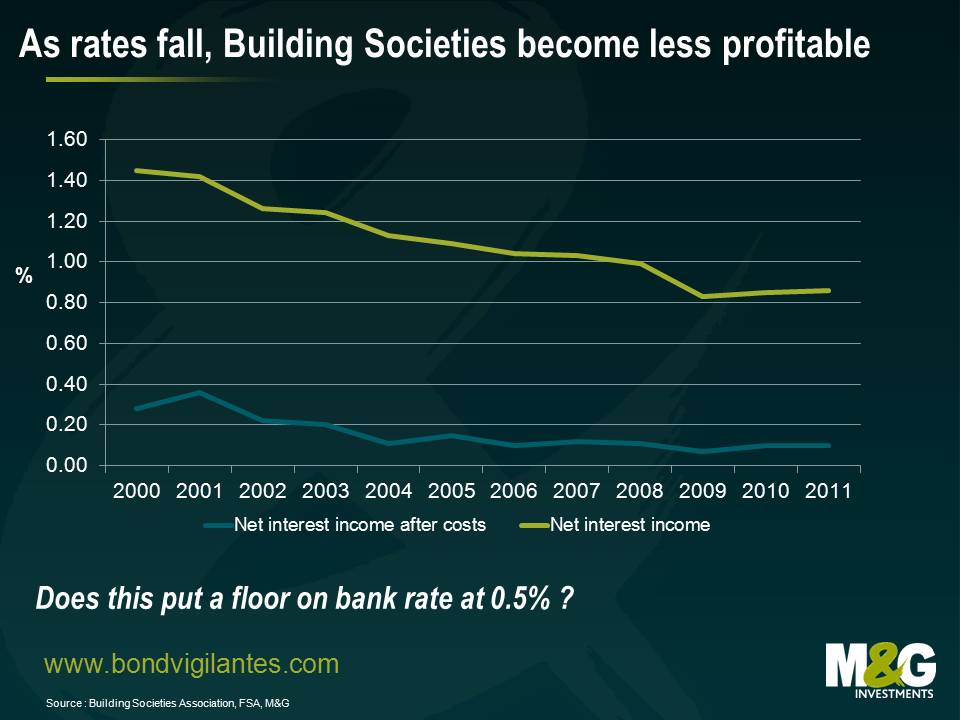

Easy right, you fly over, cut rates and give a small but welcome boost to the economy. But bank rate has been stuck at 0.5% since early 2009, through double dip recessions and increases in Quantitative Easing. There is clearly scope to cut towards zero (like the Fed) and this would clearly have some benefit to consumers and companies who have mortgages and loans linked to base rate, or Libor. But the Bank has repeatedly rejected calls to cut from here – not because those benefits might be modest (although that was a line at one point) but because the building societies might well become loss making if further cuts were made. And we need our building societies – as banks’ appetite to lend has fallen, the societies now provide 22% of gross mortgage lending compared with 13% in 2009. Why do the societies get hit disproportionately by lower bank rate? The first problem is the amount of tracker mortgages that they sold historically, where homeowners pay interest explicitly based on a bank rate plus (and in some cases MINUS) basis, so revenues fall as rates fall. And at the same time the societies have very little share of the current account market, so to fund mortgage lending they rely on having market leading savings rates to raise deposits. In recent years much of this has been done on a fixed rate basis. The chart below shows that net interest income as a percentage of assets has been falling steadily as bank rate fell from 5.5% to 0.5% over that period. Once costs are taken out (the “net of costs” margin is shown in blue) there is little room for revenues to fall before the sector becomes loss making. As for negative bank rate (mentioned by Paul Tucker as being “unlikely…but we should think about all sorts of things”), that would be even more harmful.

2 You can’t target a weaker £ because the impact on consumption is higher than the boost to manufacturing.

A competitive devaluation of the pound would lead to a windfall for our manufacturing economy as exports become cheaper. Contrary to urban myth and legend, we do make stuff (manufacturing is 12% of the economy and the UK is good at making cars, jet engines, chemicals and military hardware). Carney could use Open Mouth Policy to talk down our Winston Churchill branded currency (slogan “I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears and sweat”), or failing that intervene by printing pounds and selling them to buy foreign currencies. We could even end up with our own Sovereign Wealth Fund! Again there is a “but”. It feels like the Bank of England already tried this, and realised that it wasn’t going to work – trade weighted Sterling fell by 7% in January and February this year before Mervyn King stated that “we’re certainly not looking to push sterling down…we’re moving to a properly valued exchange rate. I think we’re probably there”. The problem is that whilst manufacturing is important, consumption is much more so. Morgan Stanley research shows that contrary to popular opinion, UK manufacturing barely benefits from declines in the pound. And rising import prices as a result of a weaker pound mean that inflation rises, which means that real incomes fall, which means that consumption falls. And as the consumption impact is greater than the manufacturing boost impact (negligible), the impact of a weaker pound on the UK economy is negative.

3 You may be the boss, but the only power is in voting last and thus having a deciding vote.

And right now 6 out of the 9 MPC members don’t want to do more monetary stimulus. You could be in the minority forever, although a prudent Governor probably realises that this kind of split might be damaging for perceptions of stability – not what you want when foreigners are net buyers of on average £6 billion gilts every month. The Canadian monetary policy framework is based on “consensus” rather than voting – my gut feel is that this delivers more power to senior Council members in comparison to a straight vote.

4 If there was a chance to review the Bank of England’s remit from the government to make it significantly more pro-growth, it may have gone.

In the March Budget, George Osborne set out a new remit: “the new remit explicitly tasks the MPC with setting out clearly the trade-offs it has made in deciding how long it will be before inflation returns to target”. He is also changing the timing of the exchange of letters between Chancellor and Governor when the inflation target is breached. And he asked the Bank to review its communications policy (it “may wish” to provide forward guidance). But Osborne didn’t wait for Carney to arrive before changing the remit and given the market’s expectations of a much more pro-growth Governor arriving (helped by Carney’s Nominal GDP speech to the CFA Society of Canada in December), these remit changes feel modest. Perhaps the only hope for a more radical Bank comes with that potential change in communications strategy – does that open the way for statements linking future rate hikes to sustained GDP growth rather than just inflation changes?

5 And finally, the UK is not Canada.

Our banks are broken (Canada didn’t even have an official bailout during the credit crisis, although some speculate there was significant support through the state mortgage agency the CMHA). Our biggest trading partner is broken (Canada’s biggest export market is the US, which is far stronger than the Eurozone). Our natural resources are in decline (North Sea oil is producing 1.5 million barrels per day compared with 4.5 million in 1999; Canada is the world’s largest uranium and hydro-electricity producer, and the world’s fifth largest energy producer in total). And most importantly Canada had its fiscal crisis in the 1990s. S&P cut it from AAA to AA+ in 1992 triggering a consensus amongst politicians to reduce the national debt burden. Debt/GDP peaked in 1996 at around 70%, and by 2002 Canada was AAA/Aaa again. The UK is in a very different economic position, and one with substantially greater fiscal headwinds than those experienced by Mark Carney during his time in charge of Canada’s central bank.

But it’s not all bad news. Although there are clear limits to what Mark Carney will be able to do, he might have luck on his side when it comes to timing. To quote Deputy Governor Paul Tucker, who spoke last night, “looking over the past year (the UK economy is) perhaps not as bad as the headline figures suggest…I think there’s a long way to go but there’s certainly reason for hope”.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

18 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox