War Loan called. Yay. Quick thoughts…

It has finally happened: the DMO has elected to call and refinance the 3 ½% War Loan, which at almost £2bn in size is by far the largest perpetual gilt outstanding. We’ve been banging on about this for years (see comment from 2011 here), and Jim is worried he hasn’t got anything to write about anymore. Jim typed up a few thoughts after the much smaller 4% Consol was called in October, here are mine.

Calling the 3.5% War Loan is a much bigger deal than the 4% Consol that was called just over a month ago. The 4% Consol is only £218.5m in size, while the 3.5% war loan is £1.938.8bn in size so is almost 10 times larger. [It’s still not exactly big though – by way of comparison, the biggest gilt outstanding, the 4.75% 2015, is £38.3bn in size].

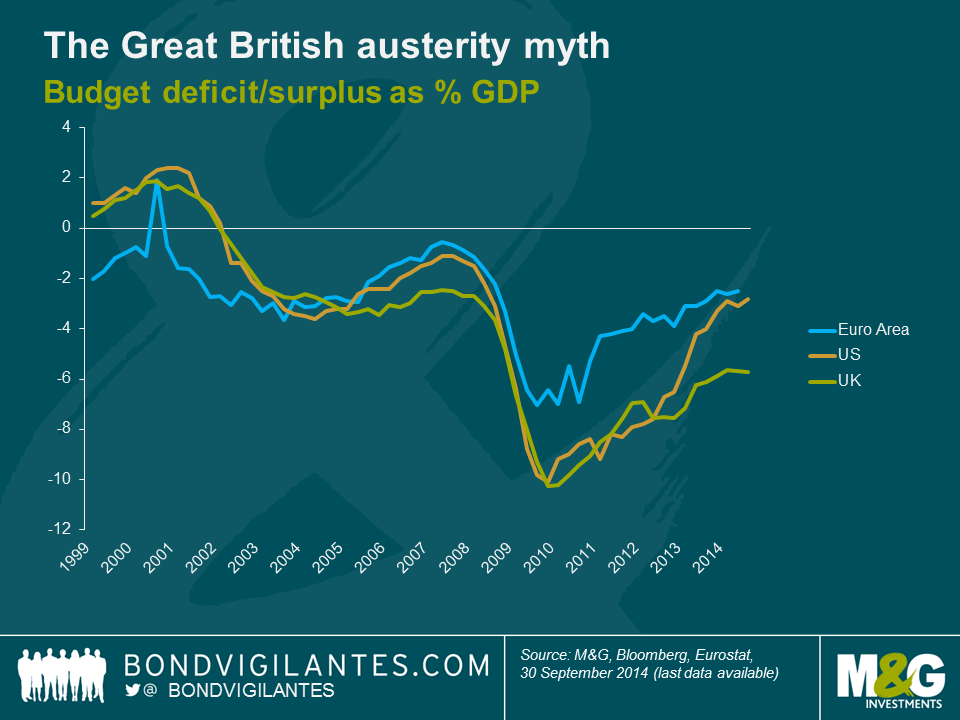

Refinancing the 3.5% war loan and 4% consol makes a lot of economic sense, as we and others have argued. But the political rhetoric that accompanied the first announcement in particular makes far less sense (today’s announcement has been toned down as bit). The stark reality is that the effect on the UK’s finances is negligible – depending upon where the gilts that refinance these bonds are issued, the decision in October to call the 4% Consol will be a saving to the taxpayer of between £2m and £3m per year, while calling the 3.5% War Loan will save around £15m per year. It’s still worth doing, but to put these numbers in context, the UK’s budget deficit this year is likely to be a bit above £90bn. Refinancing these perpetual gilts will trim the deficit by less than 0.02%.

Despite today’s toned down announcement, we’d still take issue with both the Treasury statement that the “very low interest rate environment…in part reflects confidence in the plan the government has put in place to cut borrowing and create a resilient economy” and George Osbourne’s comment that calling the war loan “is a sign of our fiscal credibility”. Government bond yields have hit record lows around the world – this is a global phenomenon, not a UK one. If bond yields were a measure of economic strength, then why are Spain’s 10 year bond yields lower than the UK’s? Why did almost every country in the Eurozone see record low bond yields earlier this week (Greece is the major exception)? And why does Japan, one of the most indebted countries in the world, currently have 10 year bond yields at just 0.44%?

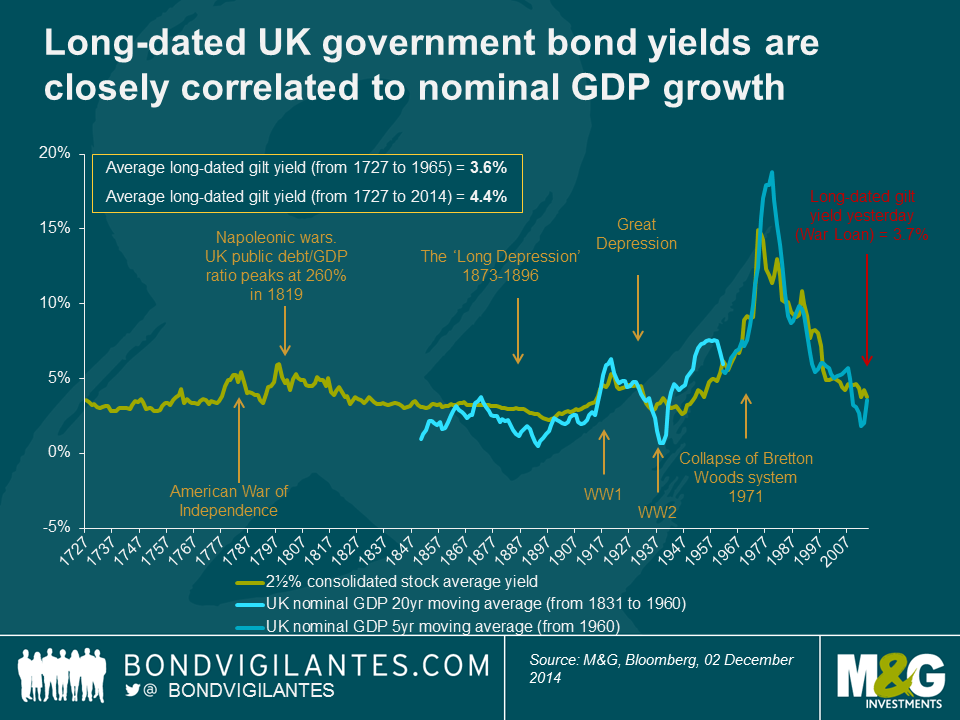

You can take the argument above further. If anything, very low government bond yields could be the market signalling its concern about very weak long term growth prospects. Below is a chart showing long dated gilt yields going back a very long way. Note the correlation with nominal GDP. So given that nominal GDP is equal to real GDP plus the inflation rate, low gilt yields today are telling us that either real GDP is expected to be very low, or inflation is expected to be very low, or a combination of the two. Looking at the index-linked gilt market, it appears that a lot of what’s driving nominal gilt yields lower is the poor growth outlook, given that very long term UK inflation expectations are almost bang in line with the average of the last 5 years (30 year breakeven inflation rates, which are priced off RPI, are 3.34%).

And finally are the UK’s finances really that strong? Beware the Great British Austerity Myth, as I’ve argued previously. Updated chart below.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

18 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox