The UK’s inflation outlook – the opportunity in inflation-linked assets

With inflation numbers in the UK moving back towards target and deflationary concerns prevalent in Europe, it is worth asking ourselves whether stubbornly high prices in the UK are a thing of the past. Whilst the possibilities of sterling’s strength continuing into 2014 and of political involvement in the on-going cost of living debate could both put meaningful downside pressure on UK inflation in the short term, I continue to see a greater risk of higher inflation in the longer run.

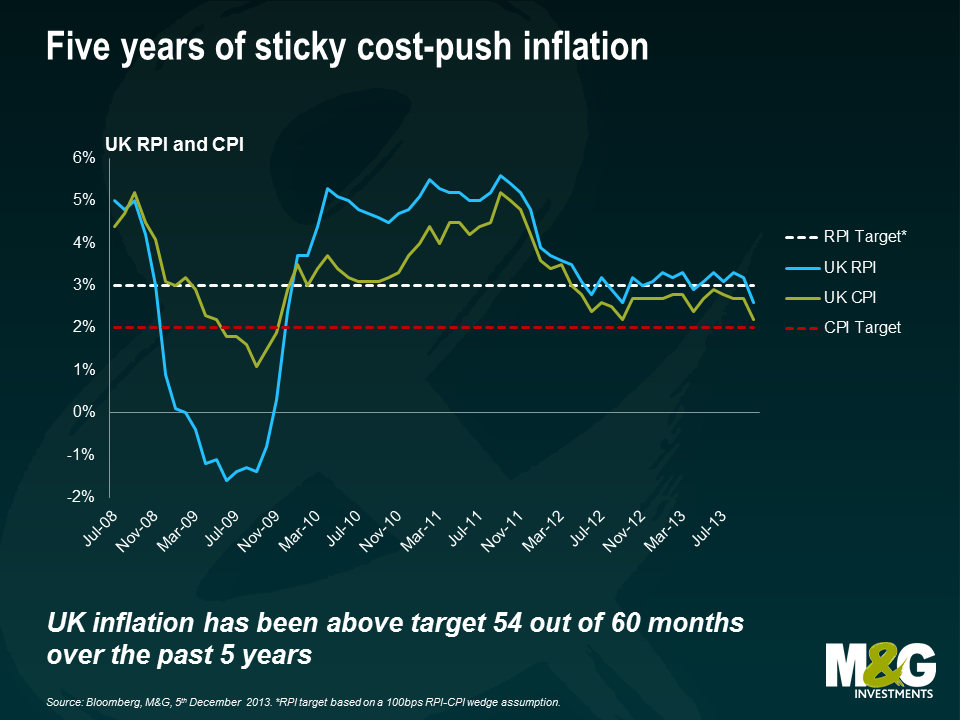

5 years of sticky cost-push inflation

The UK has been somewhat unique amongst developed economies, in that it has experienced a period of remarkably ‘sticky’ inflation despite being embroiled in the deepest recession in living memory. Against an economic backdrop that one might expect to be more often associated with deflation, the Consumer Prices Index (CPI) has remained stubbornly above the Bank of England’s 2% target.

One of the factors behind this apparent inconsistency has been the steady increase in the costs of several key items of household expenditure, together with the recent spike in energy prices which I believe is a trend that is set to continue for many years.

Rising food prices have been another source of inflationary pressure. Although price rises have eased in recent months following this summer’s better crops, I think they will inevitably remain on an upward trend as the global population continues to expand and as global food demands change.

Sterling weakness has also contributed to higher consumer prices. Although sterling has performed strongly in recent months, it should be remembered that the currency has actually lost around 20% against both the euro and the US dollar since 2007. This has meant that the prices of many imported goods, to which the UK consumer remains heavily addicted, have risen quite significantly.

Time for demand-pull inflation?

Despite being persistently above target, weak consumer demand has at least helped to keep UK inflation relatively contained in recent years. However, given the surprising strength of the UK’s recovery, I believe we could be about to face a demand shock, to add to the existing pressures coming from higher energy and food costs.

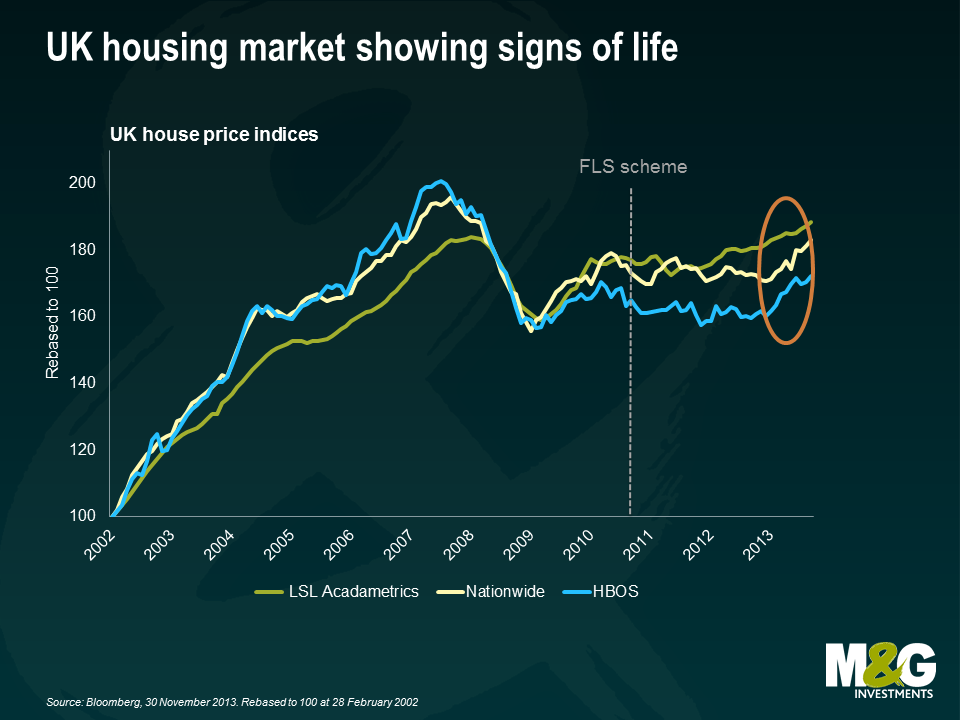

The UK’s economic revival has been more robust than many had anticipated earlier in the year. Third-quarter gross domestic product (GDP) grew at the fastest rate for three years, while October’s purchasing managers’ indices (PMIs) signalled record rates of growth and job creation. Importantly, the all-sector PMI indicated solid growth not just in services – an area where the UK tends to perform well – but also in manufacturing and construction. At the same time, the recent surge in UK house prices is likely to have a further positive impact on consumer confidence, turning this into what I believe will be a sustainable recovery.

Central bank policy…

Central banks around the world have printed cash to the tune of US$10 trillion since 2007 in a bid to stimulate their ailing economies. This is an unprecedented monetary experiment of which no-one truly understands the long-term consequences. There has been little inflationary impact so far because the money has essentially been hoarded by the banks instead of being lent out to businesses. However, I believe there could be a significant inflationary impact when banks do begin to increase their lending activities. At this point, the transmission mechanism will be on the road to repair, and a rising money velocity will be added to the increased money supply we have borne witness to over the last 5 years. Unless the supply of money is reduced at this point, nominal output will inevitably rise.

Furthermore, I am of the view that new Bank of England governor Mark Carney is more focused than his predecessor was on getting banks to lend. His enthusiasm for schemes such as Funding for Lending (FFL), which provides cheap government loans for banks to lend to businesses, is specifically designed and targeted to fix the transmission mechanism, by encouraging banks to lend and businesses to borrow. The same is true of ‘forward guidance’, whereby the Bank commits to keep interest rates low until certain economic conditions are met.

Perhaps most importantly, I continue to believe the Bank is now primarily motivated by securing growth in the real economy and that policymakers might be prepared to tolerate a period of higher inflation: this is the key tenet to our writings on Central Bank Regime Change in the UK.

…and the difficulty of removing stimulus.

With real GDP growth of close to 3% and with inflation above 2% at the moment in the UK, a simple Taylor Rule is going to tell you that rates at 0.5% are too accommodative. But it appears that policymakers are, as we suggest above, happy to risk some temporary overheating to guarantee or sustain this recovery. We believe that this is a factor we are going to have to watch in the coming years, as the market comes to realise that it is much harder to remove easy money policies and tighten interest rates than it was to implement them and cut them.

We witnessed a clear demonstration of this with the infamous non-taper event in September: as the data improved, Bernanke had to consider reducing the rate of monthly bond purchases. However, the combination of improved data and a potential reduction in the rate of purchases saw yields rise; ultimately higher rates saw policymakers state their concerns about what these were doing to the housing market recovery, and so we got the ‘non-taper’. I believe that there are important lessons to be learned from this example, and that policymakers are going to continue to lag the economic recovery to a significant extent.

Inflation protection remains cheap

Despite these risks, index-linked gilts continue to price in only modest levels of UK inflation. UK breakeven rates indicate that the market expects the Retail Prices Index (RPI) – the measure referenced by linkers – to average just 2.7% over the next five years. However, RPI has averaged around 3.7% over the past three years and tends to be somewhat higher than the Consumer Prices Index (CPI). At these levels, I continue to think index-linked gilts appear relatively cheap to conventionals.

Furthermore, this wedge between RPI and CPI could well increase in the coming months due to the inclusion of various housing costs, such as mortgage interest payments, within the calculation of RPI. The Bank of England estimates the long-run wedge to be around 1.3 percentage points, while the Office for Budget Responsibility’s estimates between 1.3 to 1.5 percentage points . If we subtract either of these estimates from the 5-year breakeven rate (2.7%), then index-linked gilts appear to be pricing in very low levels of CPI.

Current inflation levels may seem benign. However, potential demand-side shocks coupled with a build-up in growth momentum and the difficulty of removing the huge wall of money created by QE will pose material risks to inflation in the medium term. Markets have become short-sightedly focused on the near term picture as commodity prices have weakened and inflation expectations have been tamed by the lack of growth. This has created an attractive opportunity for investors willing to take a slightly longer-term view.

A reminder to our readers that the Q4 M&G YouGov Inflation Expectations Survey for the UK, European and Asian economies is due out later this week . The report will be available on the bond vigilantes blog.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

18 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox