Borrowing costs (or κόστος δανεισμού if you’re Greek)

Following on from last week’s ECB press conference, on Wednesday this week we had the quarterly Bank of England Inflation Report. Amongst the questions asked at the press conference were a couple on the serious issue of the stability and future of the Eurozone. Mervyn King refused to be drawn into commenting though, saying that “the problems are very difficult, they are very challenging, and I don’t want to make life more difficult by making any public comment that could conceivably make it more difficult for those charged to deal with it”. In one extreme he may have feared his words would be twisted to weaken the Eurozone financial system, or at the other extreme, if he were to speak the plain truth he would undermine the system.

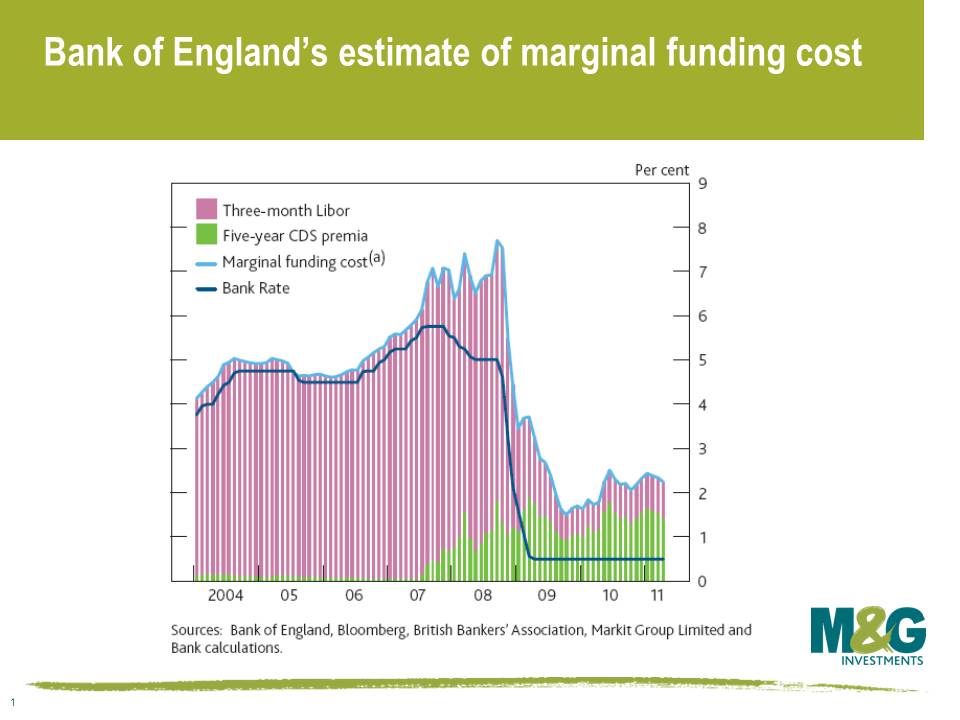

In its report, the Bank of England focused on the attached chart as one of the reasons why they had maintained the bank rate at such a low rate of 0.5%. The chart tries to create a proxy for the real cost of borrowing for the wider economy by taking 3-month libor and adding on a proxy for bank cost of bank funding (CDS). It illustrates that the official bank rate of 0.5% is equivalent to an official rate of 2% in the pre credit crunch world. The transmission mechanism between the official Bank of England ‘Bank Rate’ and the real price and availability of credit to the wider economy has dramatically altered. We are still in a credit crunch.

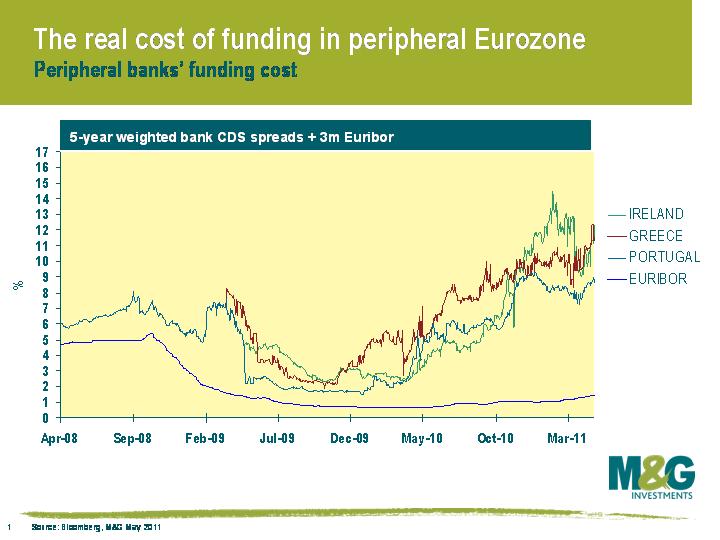

Let’s use this analysis and apply it to the Eurozone economy that Mervyn King refused to discuss. We’ve taken the biggest banks in each of Ireland, Greece and Portugal and added CDS to 3-month Euribor, where each bank is weighted equally within each country. The financial crash and the Eurozone sovereign debt crisis has meant that the cost of money has changed dramatically for these countries. There is not a single market interest rate in the single market. The true interest rate for peripheral Europe is very high, and is not exactly encouraging for growth in these countries. The Eurozone has a single official cost of financing set by the European Central Bank, but the cost of money varies dramatically between nation states and their banks.

In order to attempt to offset this effect, the ECB has been forced to intervene by funding the peripheral banks itself in return for collateral. This helps mitigate the problem but exposes the ECB to risk. The chart shows the problems these peripheral economies face in terms of a functioning financial system, and the huge task the ECB faces in implementing appropriate monetary policy for the Eurozone. No wonder the Bank of England does not want to comment directly on the problems the Eurozone faces.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

18 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox