Labour is working

Central banks set interest rates and wider monetary policy in order to stimulate demand via low rates, or to increase saving via high rates. Altering the price of money changes the behaviour of individuals and industry. This is an imprecise science with the effect always approximate and the timing usually delayed – empirically around 18 months between the policy change and the lagged outcome to inflation, growth and employment. When exercising monetary powers the central bank will always have an idea of the direction of the outcome but, like investors, will often be surprised by the real world response.

The authorities had to react quickly and decisively given the events of 2020: rates were cut, fiscal deficits increased and money was printed. This was designed to offset the negative economic effects of the pandemic response. The question at the time was: would it work, be enough, about right or too much? Given we can now examine the outcome, let’s take a quick look.

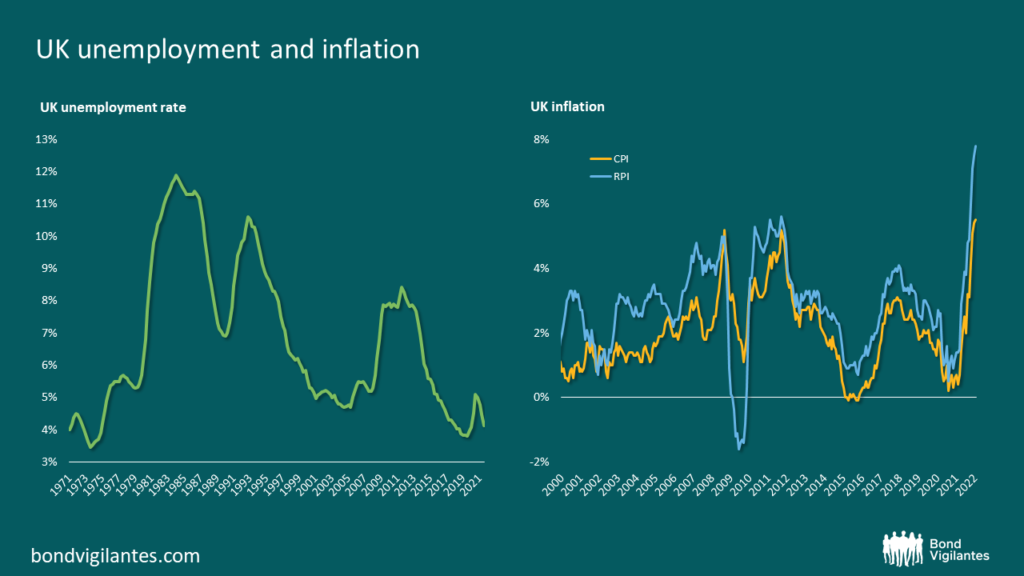

The UK economy is robust. The chart below shows that unemployment is near record lows, with inflationary pressures indicating an economy operating around or beyond full capacity. Thankfully, the financial actions of 2020 worked. What is next?

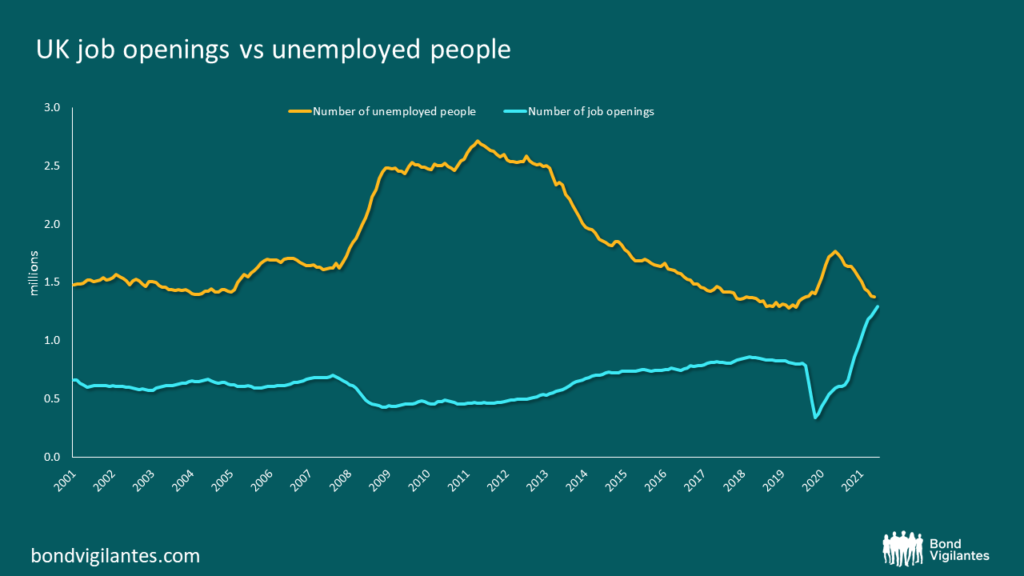

This week the ONS released its data on job vacancies, which are at record levels. Comparing job vacancies to the number of unemployed, the tightness of the UK labour market is clear (see chart below). The Bank of England is well aware of this, as it has shown by its recent and likely continuing action as it tries to reign back on previous stimulus and hit its inflation goal.

Traditionally one would look to rates being set at above inflation to discourage spending and increase saving; given a 2 percent inflation target, this was generally achieved by setting rates around 5 percent before the financial crisis. This time around, the working assumption is that the world is now different and so the market assumes that 2 percent rates would be enough to get inflation back on track. This assumption can be challenged in a number of ways, particularly with regard to the current dynamics of the UK labour market.

Before the financial crisis, the pool of excess labour in Europe was available to the UK. This has now been severely curtailed after Brexit. This means the vacancies-to-unemployed ratio is now more significant than it was in the past. I blogged specifically on the challenge facing the Bank of England and the need to raise rates in the autumn of last year. The Bank of England has to develop a new understanding of the domestic labour market post Brexit. The current hot economy will be a challenge for monetary policy implementation for central banks, and the bond markets.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.