There’s no free lunch in green bonds… or is there?

There are various interesting features linked to green bond instruments which are behind the surge of the green bond market. The defined project financing structure prevalent in green bonds allows money to be channelled to specific green projects. In addition, bondholders get additional transparency and reporting in the form of allocation and, more frequently, impact reports. A published green bond framework, which is accompanied by a second-party opinion affirming that the frameworks meets market standards such as the ICMA core principles, has become the market norm, but it does come at an additional cost to the issuing entity. These factors do conceptionally support a price premium for such instruments, also widely called a “greenium” – so too does the increasing demand for such instruments linked to the EU taxonomy.

Measuring the size of the greenium present in the market is not a simple exercise and research attempting to do so results in differing conclusions when trying to put a value to it. In my view, the cleanest way of analysing the greenium is by looking at matching bond pairs of the same issuer which share similar attributes around capital rank, currency, coupon type, duration and amount outstanding to avoid distortion due to illiquidity. Finding matching bond pairs however is not always easy, as issuers don’t usually issue ‘twin’ bonds, a concept where the green bond is identical in terms of cash flows and other bond features to a conventional bond. Twin bonds are however used by the German Finance agency which have issued some maturing in 2025, 2030, 2031 and 2050. Comparing the yield of these green bonds to its conventional twin therefore enables the greenium to be directly observed.

Germany’s green bond framework has been evaluated positively by second-party opinion provider ISS and the Bundesfinanzministerium has published an allocation report on green expenditures in May this year which underwent third party verification, both supporting the quality standards bond investors want to see. Furthermore, the German government recently published its first Impact report for green bonds issued in 2020, detailing the contribution that the green expenditures are making to climate protection, climate change adaption, mitigating environmental pollution and protecting biodiversity and ecosystems.

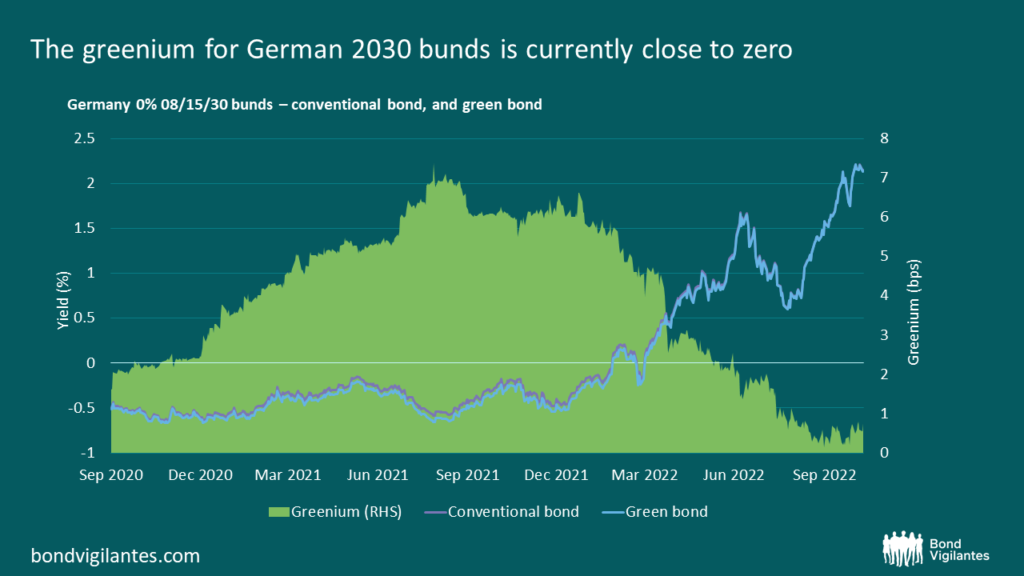

So how much extra do investors need to pay for owning such green bonds at this point in time? Not much in fact. The greenium of the DBR 0% 08/15/2030, compared it to its twin, has recently been flirting with zero, as shown in the chart below. Over the last year, the spread pick up from moving out of green into the conventional bond has fallen from 7bps to levels as low as 0.1 basis point (bps) reached in September 2022.

Source: M&G, Bloomberg (17 October 2022).

Moving to the UK, the Debt Management Office had its debut gilt offering approximately a year ago, raising £16.1 billion through two green gilt syndications. Second-party opinion provider V.E rated the UK’s Green Financing Framework as ‘robust’ and the UK’s ESG performance as ‘advanced’. Last month, the DMO published its first verified allocation report, stating that all the proceeds have been deployed with almost half of the amount raised spent on Clean Transportation projects. 27% of UK’s greenhouse gas emissions in 2019 were caused by domestic transport, the highest of any sector of the UK economy, making it a central area for reaching carbon neutrality by 2050.

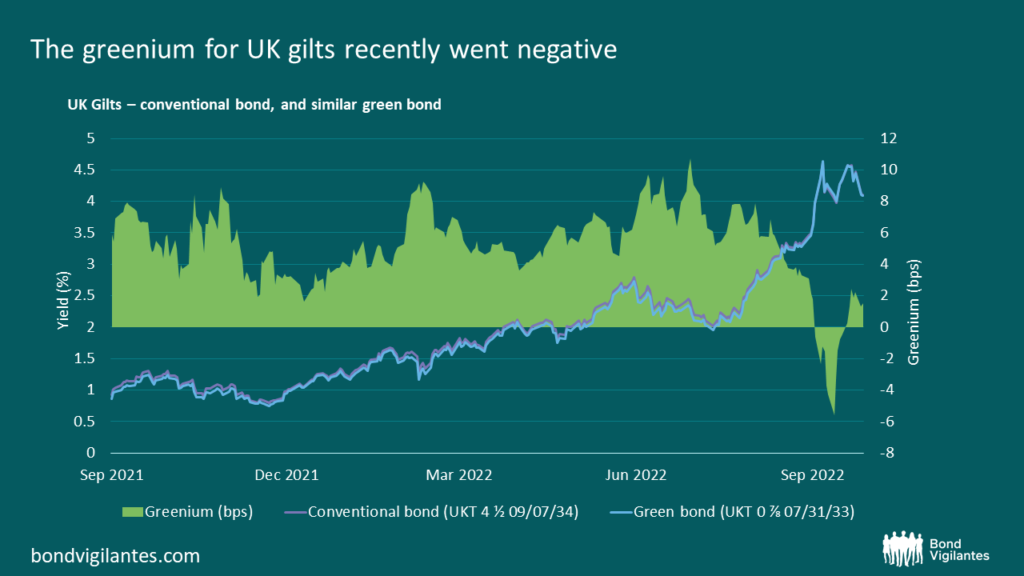

The UK, as most green bond issuers, does not use twin bonds, so the best comparator we have available to assess the greenium is the UKT 4.5 09/07/2034. Admittedly, this is a bond with slightly lower duration (given the higher coupon structure) and larger amount outstanding, but all things considered it remains a decent proxy. Since the peak in July 2022 when the greenium of the bond pair reached 10 bps, things have changed quite considerably and investors at the beginning of October had the chance – for the first time – to pick up UK Gilt green bonds at a discount.

Source: M&G, Bloomberg (17 October 2022).

There are a few technical reasons which can help to explain this move, e.g. green corporate issuance which let some bigger accounts sell the green gilts and move into corporate green deals, or the fact that the green gilts got caught in the midst of the Cheapest-To-Deliver battle for the future contract between the Gilt 32s and 34s. In any case, some of the latest price action we can observe in the green bond space illustrates that the greenium is far from static and does change over time, influencing the relative value of green bonds. It also shows that fixed income markets still struggle to effectively price green bonds versus non-green bonds. The same is the case for fully EU taxonomy aligned green bonds versus the partially aligned green bonds, but this is for another blog. For now, I stand by it: in green bond land, there is at times a free lunch available – which is good news for active bond investors.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.