Reverse factoring: a journey to improve disclosure

I work as a corporate credit analyst at M&G. I like my job, but I find it frustrating at times, for example when I have to deal with restated numbers and unresponsive management. I’m particularly annoyed by the lack disclosure around reverse factoring (also called supply chain financing), because I see that type of funding as a debt-like liability, but when it is not disclosed, I cannot be sure about my debt and leverage calculations which are key in my credit analysis. In addition reverse factoring has contributed to a number of high-profile defaults like Abengoa and Carillon, indicating that disclosure is warranted. A few years ago I decided to turn my frustration into a personal mission to lobby for better disclosure.

To start, I will explain my concerns in relation to the lack of disclosure on reverse factoring.

In order to understand this financial product, it is useful to begin with conventional factoring. Conventional factoring is a form of invoice finance enabling earlier cash conversion of trade receivables, in many respects similar to invoice discounting. Factoring can be done on a recourse basis (the company remains liable for any invoice) or non-recourse basis, which transfers the non-payment risk to the factoring company.

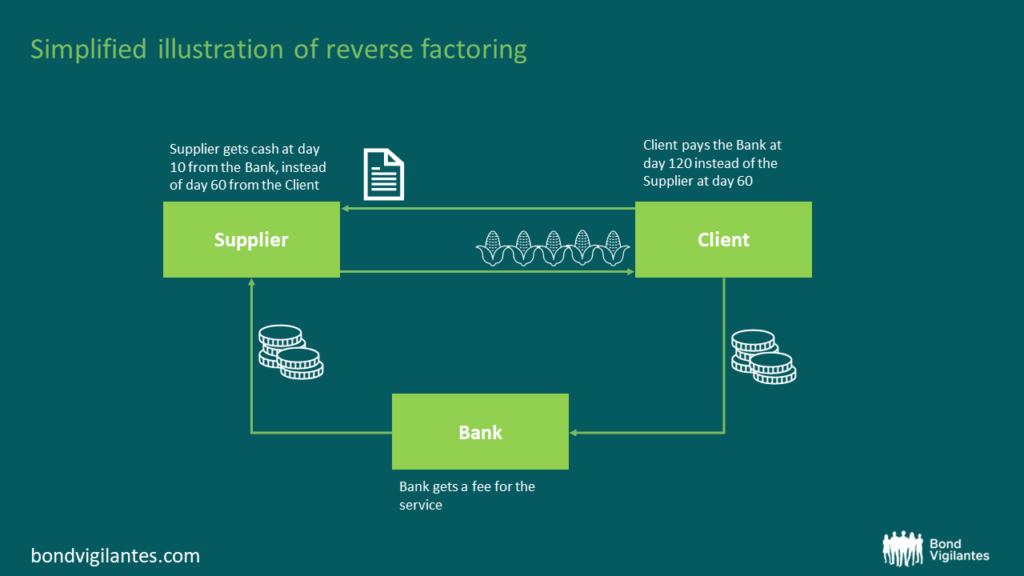

While conventional factoring is initiated by a supplier of goods and services, reverse factoring is initiated by the customer (hence “reverse”). I’ll use a practical example to illustrate it. Let’s assume that standard payment terms for goods or services are 60 days in a given industry and they are delivered on day 0. The customer acknowledges the invoice, say on day 10. The acceptance of the invoice allows a bank to advance payment to the supplier on day 10. If the customer then paid the bank in line with “normal” payment terms, say on day 60, reverse factoring would look identical to conventional factoring. However, reverse factoring also enables later payment by the customer by extending its payment terms to the bank say to 120 days from 60 days. The supplier is indifferent because it is being paid on day 10 by the bank in any case, but, by stretching the due date, the customer is able to extend its payables beyond the standard commercial terms. The funding gap so created through an extension of payment terms and an earlier cash conversion for receivables is funded by a financial institution.

Even though this is a date-certain payment obligation to a bank, current accounting standards allow the liability to be reported among trade or other creditors rather than as financial debt and it is generally not disclosed separately. For this reason, investors might not be aware of this debt-like liability. This represents a problematic blind spot for a number of reasons (under-reported financial debt, distorted operating cash flow and working capital), but especially because default risk can be exacerbated by these arrangements, which are generally short-term in nature and can be pulled at short notice. When banks pull out of these lines, the resulting working capital shock can potentially trigger a liquidity crisis that could lead to the issuer’s default, without any warning sign for investors. A number of high-profile defaults (Carillon, Abengoa to name just a few) have abundantly illustrated how this instrument can exacerbate default risk. Overdependence on reverse factoring can create a critical vulnerability if the borrower cannot reliably withstand cancellation of the facility, an event that is all the more likely to occur when the credit quality of the borrower deteriorates.

My concerns are not around reverse factoring itself, which can provide tangible benefits in particular to the customer base of a strong IG credit by improving their collection terms. My concerns relate to the disclosure gap under current accounting standards which potentially allows companies to hide debt-like liabilities and critical vulnerabilities.

And now I would like to give you a very brief account of how we sought to address this. I started my journey in January 2020 discussing the matter with Rupert Krefting, head of Corporate Finance and Stewardship at M&G. He introduced me to the Financial Reporting Council and the Company Reporting and Auditing Group (CRAG) at the Investment Association (IA) where I was able to voice my concerns . I then joined the European Leveraged Finance Association (ELFA), a newly formed buy-side association for high yield investors, as chair and then co-chair of the Disclosure and Transparency committee. Along with Russell Taylor of JPM, the other co-chair, we engaged directly with the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB, a private-sector body setting the International Financial Reporting Standards, IFRS) and its board members in a number of video calls. Two events significantly contributed to and accelerated the process: i) a public letter by Moody’s to the IFRS dated 31st January 2020 highlighting the disclosure gaps on reverse factoring arrangements, in response to which the IASB opened a consultation, ii) the collapse of Greensill, a financial company based focused on supply chain financing, in 2021.

In February 2023, the IASB tentatively agreed to introduce relevant additional disclosure under IFRS in quarterly and annual reports, for periods starting from 1 January 2024. However, reverse-factoring liabilities will continue to be reported as trade and other payables and not as financial debt, as we would have liked to see. This means that analysts will have to pay special attention to the relevant notes in the Financial Statements. Similar disclosure requirements have also been introduced for companies reporting under US GAAP in quarterly reports to March 2023.

I like to think that we have contributed to a positive outcome, although we were just one of the many voices the IASB listened to. We have found the IASB and its board members very keen to engage, explain and listen. Admittedly the process took longer than initially anticipated, but it’s understandable that changes to accounting standards are not rushed through.

Reverse factoring is not the only accounting blind spot for bond investors: disclosure of conventional non-recourse factoring, inconsistent EBITDA reporting, disclosure of capex funded with leases (an issue exacerbated by the adoption of IFRS-16) should also be addressed in my view. So the credit analyst’s mission for better disclosure continues and will probably never end, like my frustration.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.