SVB is a big deal, but not for bond investors in larger US and European banks

What do you get when you have a $200bn bank fail in a high inflation, slow-growth, rising rate environment? While “contagion” or “global systemic risk” are reasonable answers, we don’t think either will ultimately prove accurate in the case of Silicon Valley Bank. Yes, there will be challenges for SVB clients and potentially meaningful pressure on other specialty lenders or banks with particularly weak deposit franchises, but in our view the events of last week do not pose a material risk for bond investors in large diversified US banks, and they pose even less risk for bond investors in European banks. One reason is that several key factors in SVB’s demise relate to its unique business model. Another is that several broader factors that contributed to its stress aren’t as prevalent in Europe as they are in the US. Investors may argue (correctly) that SVB severely mis-managed its interest rate risk and this could occur at any bank, but the confluence of factors that combined to bring down the 16th largest bank in the US is simply hard to find at any decent-sized diversified lender on either side of the pond. And, importantly, it doesn’t appear that any large banks have worryingly large exposures to SVB.

A Unique Business Model…

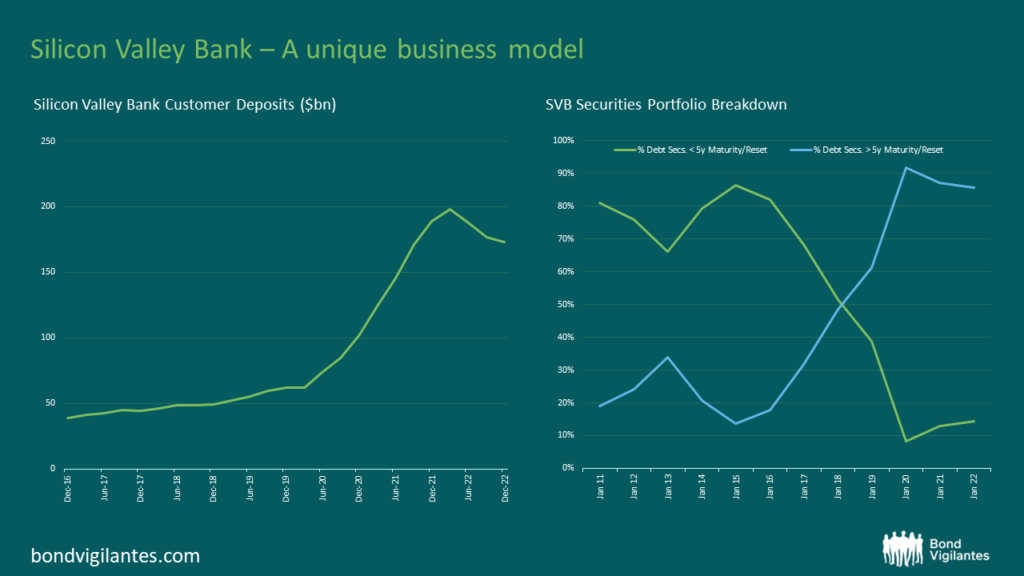

As widely reported, SVB focused heavily on providing banking services to private equity (PE) funds, venture capital (VC) funds, and tech start-ups. As investments in technology firms soared during the pandemic, so did the deposit base of SVB, from about $60bn at the end of 2019 to almost $190bn two years later (see chart). That growth is far faster than the 34% rise in total US bank deposits over the same period. The vast majority of SVB’s deposits were easy-access, relatively large, and not FDIC-insured (96% uninsured to be precise, compared to less than 50% at most US banks). Not being a traditional lender – about half of its loans were to PE/VC firms – it poured most of the $130bn influx in deposits into government securities. More specifically, it bought tens of billions of longer-dated Treasury and agency mortgage-backed securities (MBS) which had virtually no credit risk, but would fall in price if rates rose sharply. And rise, they did.

This is common practice for most US banks, and is not a concern by itself. Holding a government guaranteed MBS is probably better economically for a bank than holding the underlying mortgages as loans: agency MBS have a little lower yield, but virtually zero credit risk and much greater liquidity. More importantly, while both fixed-rate MBS and loans fall in value when rates rise, banks typically benefit from rising rates. This is because their cost of deposits almost always rises much more slowly than (and less than) interest rates on their floating rate loans or cash equivalents. Rising rates are especially beneficial for banks with plenty of no-interest transaction accounts. Bank of America has over half a trillion dollars in MBS, yet it’s still one of the stronger and more profitable banks globally, thanks in part to its largely retail $1.9tr deposit base.

Source: SVB, SNL.

… was Key to SVB’s Demise

So what happened to SVB, a bank with very good asset quality, profitability and capital metrics? There were two primary problems, neither of which would have likely caused their downfall had the other not occurred at the same time. The first is that SVB’s deposit base was extraordinarily concentrated in a single, financially-savvy group of firms which were all exposed to the cyclical risk of PE/VC funding drying up. As money flowing into high-risk private investments slowed last year, PE/VC sponsors and their cash-hungry start-ups began drawing down on their deposits at SVB. The bank lost $25bn, or 13%, of deposits in the last 9 months of 2022, and another $8bn in January and February, but there was still no “run-on-the-bank” and, had this risk been better appreciated, probably wouldn’t have been one last week.

The second problem was the bank’s decision to put most of its excess liquidity in long-duration bonds without sufficiently hedging rate risks, so when it decided to start selling bonds to fund deposit outflows, it began to incur losses. It’s unclear why the bank changed its pre-2017 policy of holding mostly shorter-dated securities (see chart); presumably it got greedy and sought higher margins, thinking its deposits were “sticky”. It’s also unclear why it didn’t (or couldn’t) borrow more in Federal Home Loan Bank advances or in repo markets, and instead sold some bonds at a loss and announce a capital raise to rebuild optically strong capital buffers. The capital raise seemed to spook its sophisticated depositors, who, smelling trouble, started to pull their deposits en masse. Once that happened, the end came swiftly.

Are other US banks at risk?

While the same dynamics might occur at other specialized lenders, it’s difficult to see larger traditional lenders – both large regional and “global systemically-important” US banks – suffer a similar fate. The vast majority of SVB’s deposits were large, uninsured, and owed to sophisticated PE/VC customers exposed to the same cyclical funding risks. That concentration is unique among US banks with material public debt outstanding. Compared to SVB, these banks have smaller exposure to long-dated MBS, far larger amounts of retail insured deposits, typically greater access to wholesale funding, and hopefully better interest rate risk management. Fortunately, it doesn’t appear that any large US lender has a worryingly-large exposure to SVB, given most of its funding was from deposits.

Other US banks will of course be affected. Those with weak or highly-correlated deposit bases are understandably already under scrutiny and/or market pressure, and in the near-term, they may lose some deposits to larger, stronger institutions, adding to their struggles. Of course, the larger banks should accept and price such deposits carefully, knowing how fleeting they may be. We also expect the banks and their regulators to look more closely at deposit base dynamics and pricing. One positive we envision for bond investors is that banking lobby opposition to stringent capital and liquidity rules is likely to be quieter, if not silent, for some time. Instead, the events of last week will likely encourage the Fed, which is already in the midst of a “holistic review” of bank regulation, to meaningfully enhance its oversight of smaller banks.

Are European banks at risk?

Like their US counterparts, most large European bank issuers tend to have more diversified, more stable and more insured deposits than SVB. There are other reasons, however, that European banks are not likely to suffer the same pressures as California lender. One is that money-market funds in Europe do not provide as much competition for bank deposits as they do in the US, so we expect European banks to continue to benefit from rising rates (albeit more on the continent than in the UK where the benefit of further rate hikes may wane). A second reason is that European regulations regarding liquidity, interest rate risk management and stress-testing are in several ways more robust than the regulations that applied to SVB; US regulation for banks smaller than $250bn in assets were eased quite a bit in 2018. A third reason is that European bank liquidity portfolios are less sensitive to rate rises than those of most US banks. There’s nothing like the US 30-year fixed MBS market in Europe and most of European banks’ liquidity is held at central banks or in relatively short-term government bonds. As a result, the risk of rapid deposit outflow which cannot be safely funded by security sales or borrowing should be lower in Europe than it is in the US at the moment.

Conclusions

SVB’s insolvency is a big deal. Up to half of the US PE/VC community may have exposure to the bank, either directly or indirectly, and any sizeable bank failure can trigger fear in the market, justified or not. The bank’s demise will likely cause liquidity problems for depositors, though this should be mitigated by the Fed’s backstop for all SVB deposits, including the uninsured ones. In addition, the developments are likely to put stress on smaller/specialty lenders (especially those with weak deposit franchises), damage the reputation of US and California regulators (it was state-chartered, not national), and test the ability of the FDIC to limit collateral damage when implementing the bank’s “living will”. It seems fear has already helped force another bank into receivership, as over the weekend the $110bn Signature bank in New York has failed. Like SVB, Signature grew assets very rapidly in recent years, had a concentrated, mostly uninsured deposit base (crypto-currency firms in particular), and was state-chartered. While SVB is a major failure, SVB and other niche players like Signature are quite unique in the broader banking world. So unique, in our view, that it is unlikely to create material problems for any of the large diversified banks in the US or Europe from a credit point of view.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.