Tokyo Takeaways – Macro FMs in Japan

Jim and I have recently come back from a fascinating trip to Tokyo, meeting multiple economists, strategists and government officials. What is clear is that trying to navigate Japanese bond markets against the current macroeconomic backdrop, both domestically and globally, may be even harder than watching the two of us trying to navigate the Metro.

Let’s start with Yield Curve Control (YCC)

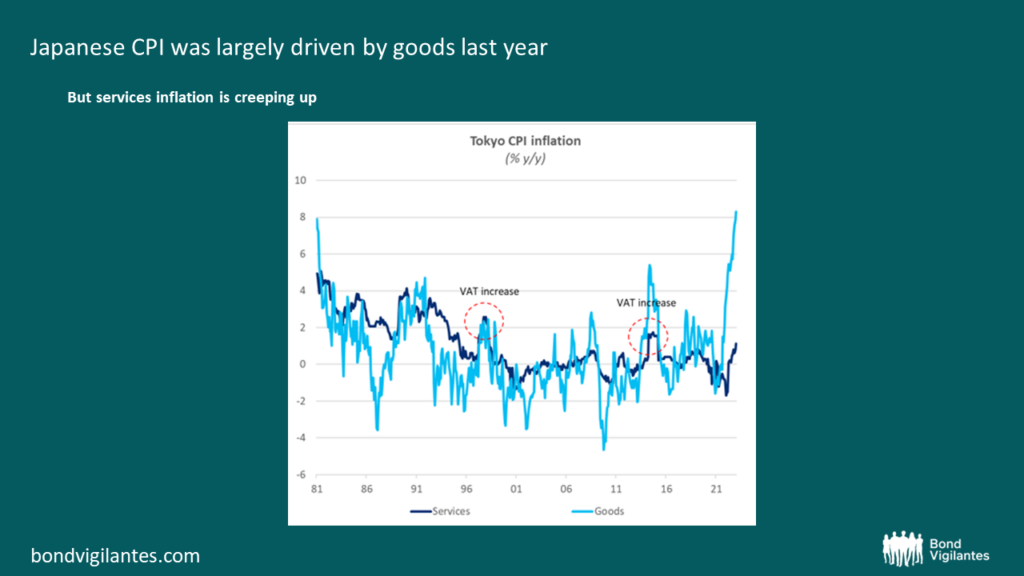

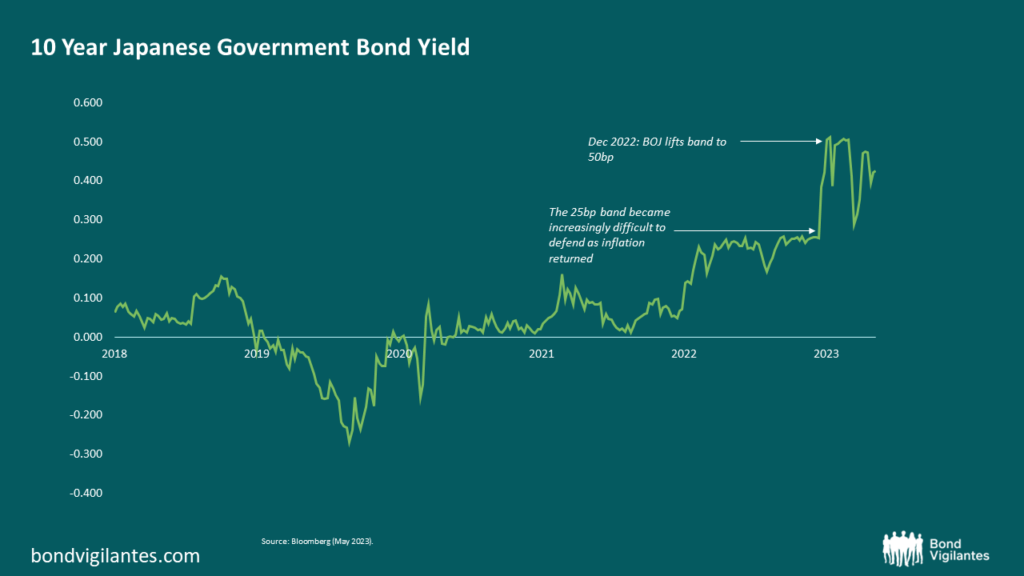

Why didn’t new governor Ueda change YCC policy at the latest meeting? Whilst we heard conflicting expectations for upcoming meetings, a key theme was that the Bank of Japan (BOJ) want some inflation. They want to have more flexibility to use monetary policy effectively. Currently, with YCC capping 10yr yields at 50bps and rates at -0.1%, they have nowhere to go in an economic downturn. Of course, they widened the YCC band in December (the amount yields are allowed to fluctuate either side of their 0% target), which prompted investors to speculate on further policy exit, but this was a result of pressure from Kishida’s government given a very weak Yen (JPY). If the BOJ had their way, I suspect they would have continued with the +/-25bp band. Broadly, their inflation forecasts are not predicting sustainable inflation of 2%, with the 4% CPI prints we saw late last year/earlier this year being largely driven by non-core constituents (food and energy). At the latest meeting, Ueda announced they would be reviewing monetary policy over the next 12-18 months. This effectively buys them time – they are hesitant to curb this potential inflation too soon.

Source: Citi, Haver

Now the Yen has stabilised somewhat, it feels like YCC is here to stay in the short term. Not only does the BOJ want to see further proof of broader inflationary pressures, but the current 10yr tenor also largely favours the government. They are the biggest borrower by far at the 10yr point – the BOJ now own over 100% of the Japanese Government Bonds (JGB)s here (they also lend the bonds to speculators). Given the big fiscal packages they are using to support the economy (electricity/energy bill subsidies etc) in the short term, plus the longer-term funding requirements of vast state pension payouts in an ageing economy (their low birth rate is a persistent problem for tax revenue projections), it’s not likely that they will be trimming borrowing anytime soon. They could shorten the tenor of YCC to 5yr to support corporate funding rates (corporates are generally bigger borrowers at the 5yr point of the curve), but they likely want to buy time for the government to slow down borrowing and/or for signs of stress to appear more in corporate balance sheets – right now they’re in good shape.

The removal of forward guidance

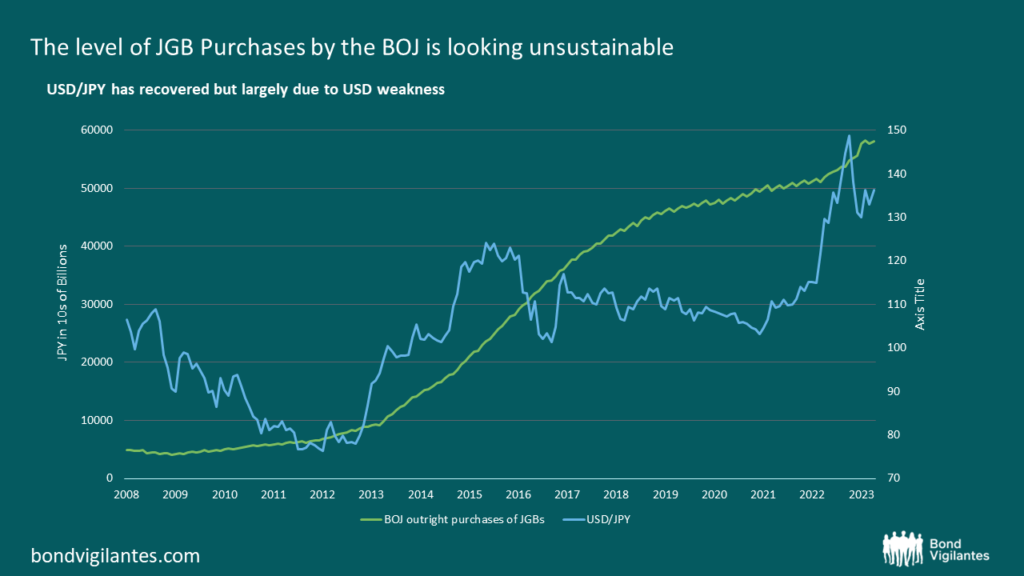

What this 12-18 month window also does, is reintroduce the possibility of surprise. The current YCC policy has prompted extraordinary levels of JGB purchases to defend the cap. If they were to provide clear forward guidance on a further widening of the band, this essentially offers free handouts to speculators who execute short trades that stop out at the top end of the YCC band (i.e. when the BOJ comes back in to buy JGBs). The 12-18 month timeline doesn’t mean they won’t do anything for the next year, and if they do, the element of surprise returns.

Source: Bloomberg (May 2023).

Source: Bloomberg (May 2023).

The risk of holding off on normalisation

Are BOJ now entering Team Transitory? The risk of the BOJ holding off and letting inflation run hot for a while (given they’re convinced we still won’t see sustainable 2% inflation over the medium term) is one we’ve seen before. We saw central banks pushing this narrative in the US and Europe, focusing on non-core food & energy inflation, then being hit by persistent, sticky high service sector inflation amidst continuingly strong labour markets. Whilst the magnitude of Japan’s inflation problem definitely feels smaller, the risk of focusing on external influences and being complacent about stickier inflation feels very familiar. A challenge here is how the BOJ actually measures ‘sustainable 2% inflation’. An example is they focus highly on the Shunto spring wage negotiations (that this year saw pay rises in big corporations negotiated at above 3%, the highest figure in 30+ years), but given these are annual it’s hardly an explanatory data point. But broadly, wage growth remains firm and well above long-term trends.

The situation is complicated

It won’t be straightforward for the BOJ to make future policy changes. They want to remove YCC eventually (and would likely do this before they lift policy rates out of negative territory), but are determined to narrate that it is just to improve ‘market functioning,’ rather than to tackle inflation. Nonetheless, they are hedging themselves – they have introduced policies that make it more expensive to short JGBs outright, including tighter lending facility conditions, as well as introducing a 5yr lending programme to banks, i.e. negative funding rates to encourage them to buy JGBs. This feels contrarian vs their narrative to improve market functioning, but they know that markets are determined to adjust yield expectations higher in response to the latest 4%+ inflation prints. Life insurers have already accumulated large cash reserves, and regional banks are piling into bear funds (filled with pay fixed positions in swaps and short futures) to hedge their exposure.

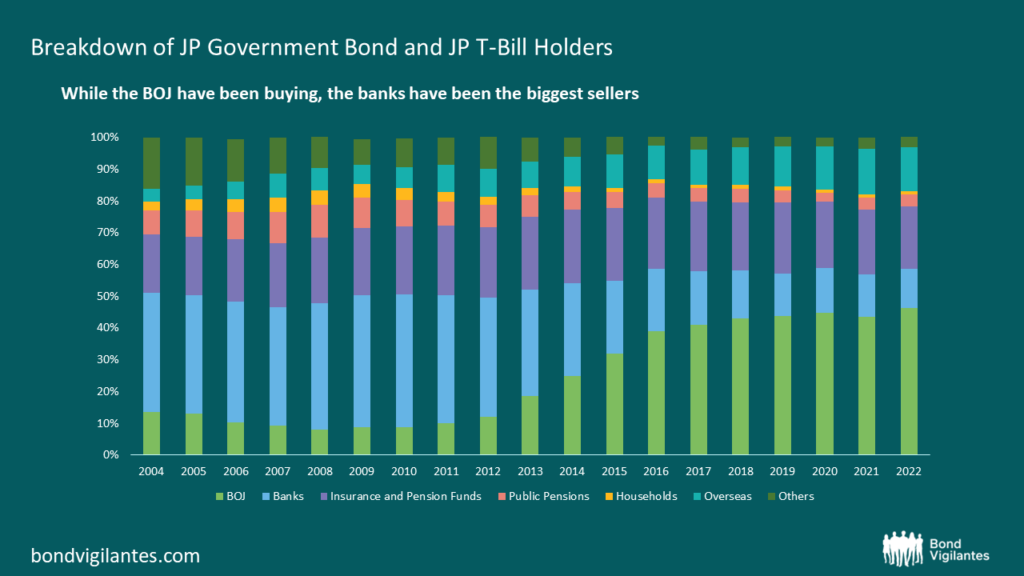

It is no surprise the BOJ are hesitant to tighten policy, whether through exiting YCC and/or negative interest rate policy (NIRP). The elephant in the room, as always, is the BOJ’s huge balance sheet. As Debt/GDP in Japan has soared above 250% (and it is already vastly larger than other DM economies), the supply has been absorbed by the central bank, who now own over 50% of outstanding JGBs. Continuing this level of purchases also puts downward pressure on the Yen, which we know the government doesn’t like (but they definitely won’t like being unable to service their debt stock through higher yields either). If they start some sort of quantitative tightening (QT), it is not clear who would absorb the demand. The lifers have cash to spend at the long end, but the banks have been reducing their JGB holdings substantially.

Source: Bloomberg (May 2023)

Will the banks come back in to buy JGBs if yields become more attractive and the yen becomes more expensive to hedge? We have seen some flow repatriation with Japanese investors selling a record amount of overseas debt last year, and with over $3 trillion of overseas holdings, a mass exit would cause a huge swing in global markets. But here’s the catch. The national banks are protected, as they can buy offshore bonds (e.g. US treasuries) through repo markets, meaning they aren’t vulnerable to the higher costs associated with FX hedging a potentially stronger JPY. As they are not forced to re-enter domestic markets by a stronger Yen, it will be pure relative value of JGB yields vs other markets that drives the banks home, and this would likely be driven by an exit of NIRP rather than changes to YCC.

What can we conclude from all of this?

The government and BOJ are stuck between a rock and a hard place. To some extent, it may be prudent for the BOJ to wait it out and hope for some sort of policy error from the Fed/a banking crisis in the US that forces the Fed to cut rates and drives investors back into JGBs and supports the Yen. If yield differentials narrow via lower US Treasury (UST) yields, this may support JPY/USD without the BOJ having to meaningfully raise interest rates. Plus, if inflation doesn’t turn into a sticky services-driven monster, then they may not have to choose between defending the currency or being unable to service their debt.

That all sounds very optimistic, and realistically with the risk of higher inflation – a risk we haven’t seen in Japan for decades – in an economy with extraordinary debt levels that is now majority owned by its own central bank, we came away from Tokyo most concerned about Japan’s commitment to Team Transitory. We have seen this in other developed bond markets, and we know that it can unravel quickly.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.