UK Government debt interest payments set to weigh heavy

The United Kingdom’s Government debt interest payments have been a topic of concern and scrutiny for many years. As one of the world’s largest economies, the UK has amassed a significant amount of debt, and the cost of servicing this debt has important implications for the nation’s fiscal health.

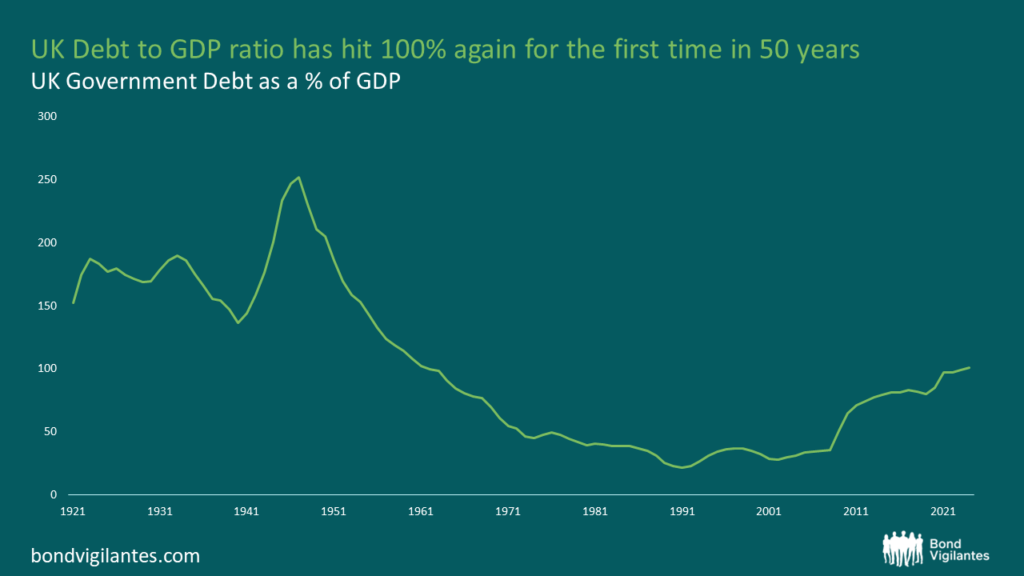

The current state of UK Government Debt as of 2023 is circa £2.5 trillion, which is 100% of GDP and equates to £38,000 per person.

Source: ONS (July 2023)

Source: ONS (December 2022)

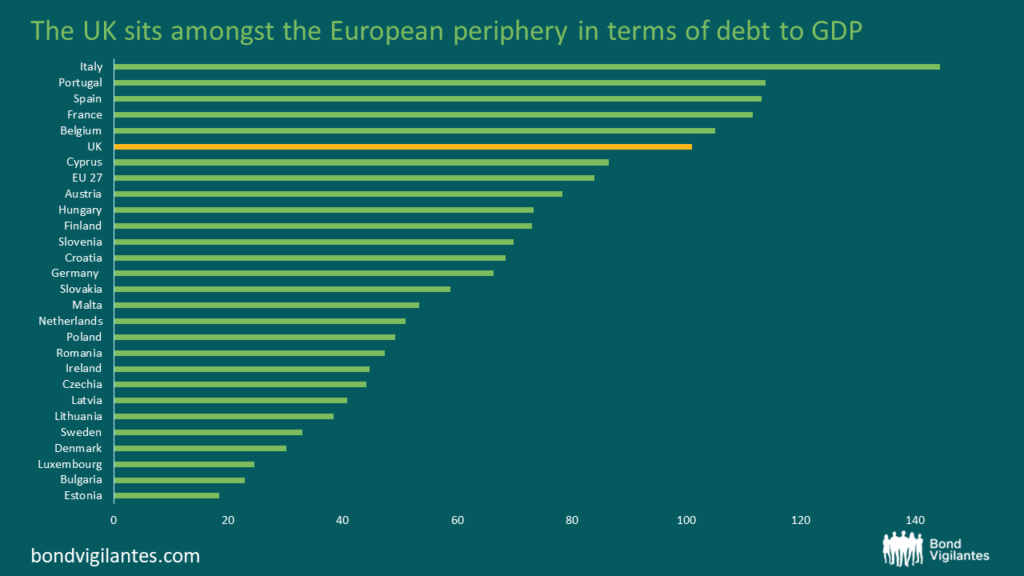

On a comparative basis, the UK is not the worst, but is sitting in amongst the likes of Italy, Portugal and Spain, which were embroiled in their sovereign debt crises only a few years ago. Although the crisis was the result of a number of factors, debt sustainability was the central cause.

Debt has accumulated and accelerated since 2008 through various channels, including government borrowing to fund budget deficits, economic stimulus measures, infrastructure projects and social spending. The low-interest rate environment since the 2008 global financial crisis has masked this growing problem and has helped keep debt servicing costs relatively manageable.

However, there is no sign of the low-interest rate environment returning anytime soon. So, this begs the question: are the chickens finally coming home to roost?

What are the factors contributing to future increases in debt servicing costs?

There are three key factors which are set to make the debt burden increasingly costly to service and maintain.

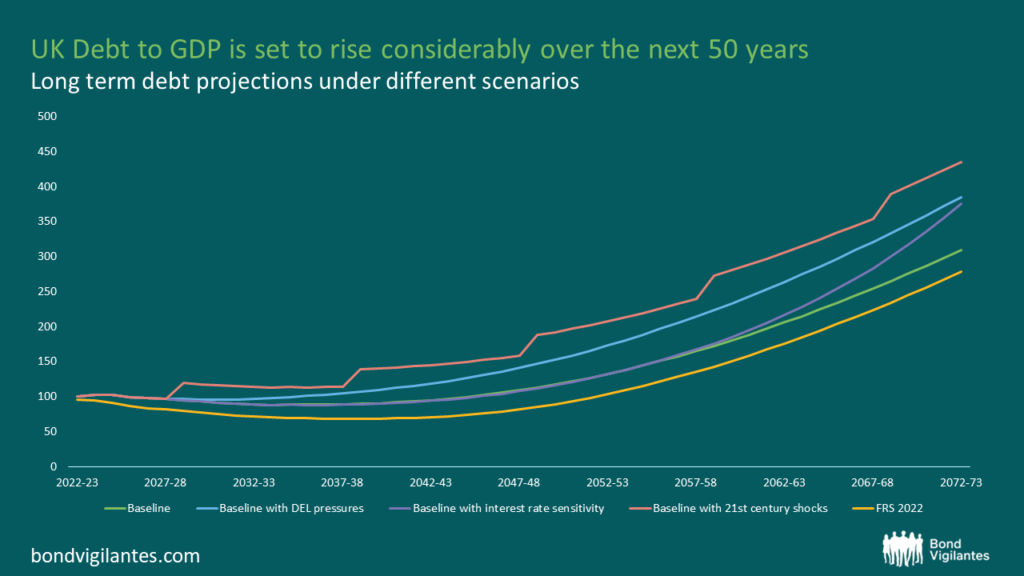

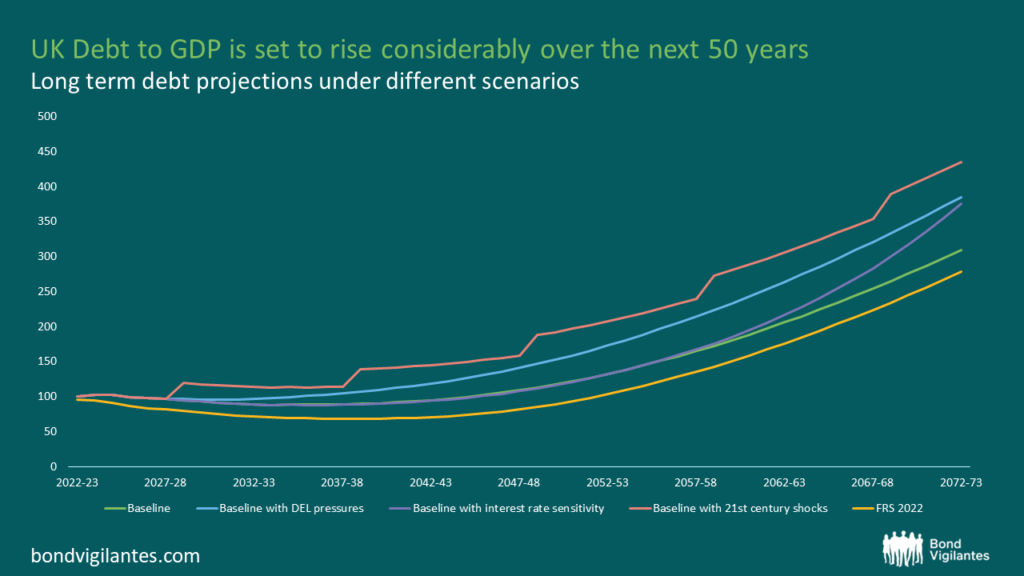

- Rising Debt Levels: The UK’s debt levels will most likely continue increasing due to ongoing fiscal spending and increased future spending toward a net zero economy. As debt levels rise, the government will need to issue more bonds, which should result in higher interest payments. Looking at the future projection from the OBR, debt is going up under all modelled scenarios.

Source: OBR (July 2023)

- Interest Rate Increases: Interest rates have been extremely low for many years, which has allowed the UK to build up the current outstanding debt stock. This anomalous period has ended abruptly, with interest rates moving meaningfully higher. As central banks normalise their policies, the rise in interest rates increases the cost of borrowing for the UK Government, and as a result, debt interest payments increase.

- Inflationary Pressures: Interest rates increase as central banks attempt to ward off the harmful impact of inflation. If the UK experiences sustained inflation, it could result in higher interest rates and, consequently, higher debt servicing costs through inflation-linked debt.

It’s vital that the Government gets on top of the ever expanding mountain of debt. As this grows the economy becomes increasingly exposed to changes in interest rates and inflation.

What are the implications for the economy from rising debt interest payments?

Rising interest payments and the knock-on costs of these have subsequent impacts in the wider economy. Further action from the Government may also be necessary. Some measures may include the below:

- Fiscal Constraints: Higher debt servicing costs will limit the Government’s ability to allocate funds to other important priorities, such as public services, infrastructure, and social programs.

- Austerity Measures: To manage rising debt interest payments, the Government may seek to implement austerity measures, such as spending cuts and tax increases. These measures will likely slow GDP growth. Many will feel the remembered pain of austerity in the wake of the Global Financial Crisis, which may mean the measures will be difficult to implement.

- Credit Rating Concerns: The deteriorating fiscal situations lead to concerns from credit rating agencies, resulting in downgrades that make borrowing more expensive for the Government. Up until 2008, the UK was rated AAA. Since that time debt has continued to increase and the credit rating has fallen, only marginally, to AA negative. It’s probably fair to say that future downgrades are a possibility in the case of rising debt payments.

- Crowding Out: Increases in government borrowing could crowd out private sector investment by absorbing a larger share of available funds in the credit market. This could hinder economic growth and innovation.

The Government needs to manage these rising debt interest costs seriously, as they could very well start to drive policy.

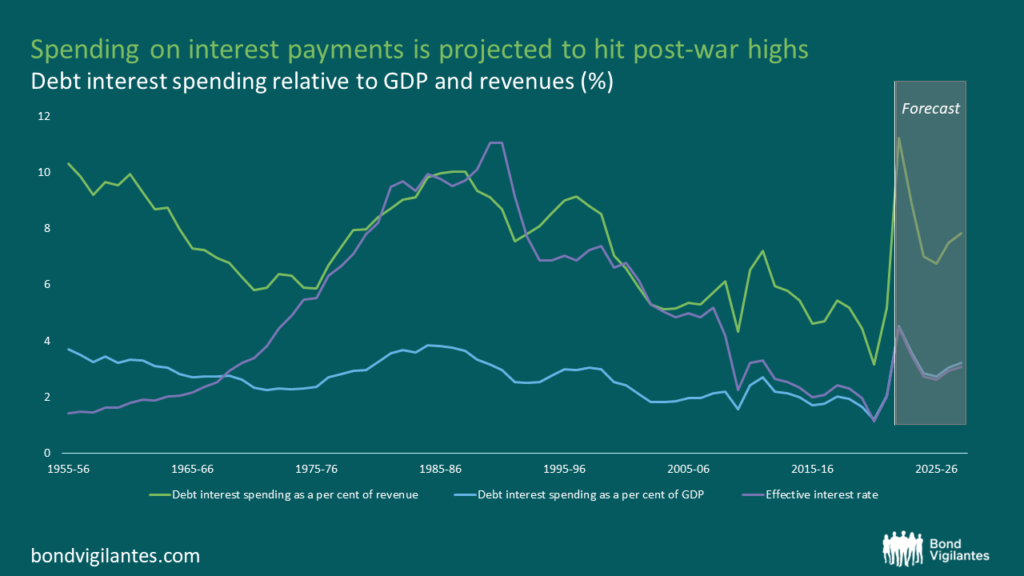

The below chart shows debt interest spending relative to GDP and revenues. This figure is projected to get to its highest since the post-war period over the coming 5 years.

Source: ONS, OBR (March 2023)

Let’s look at the two components of the debt interest spending-to-revenue measure and try to understand how the UK can get on top of this worrying trend.

Revenues

Revenues are broadly a function of Taxes – Income, Corporation and VAT.

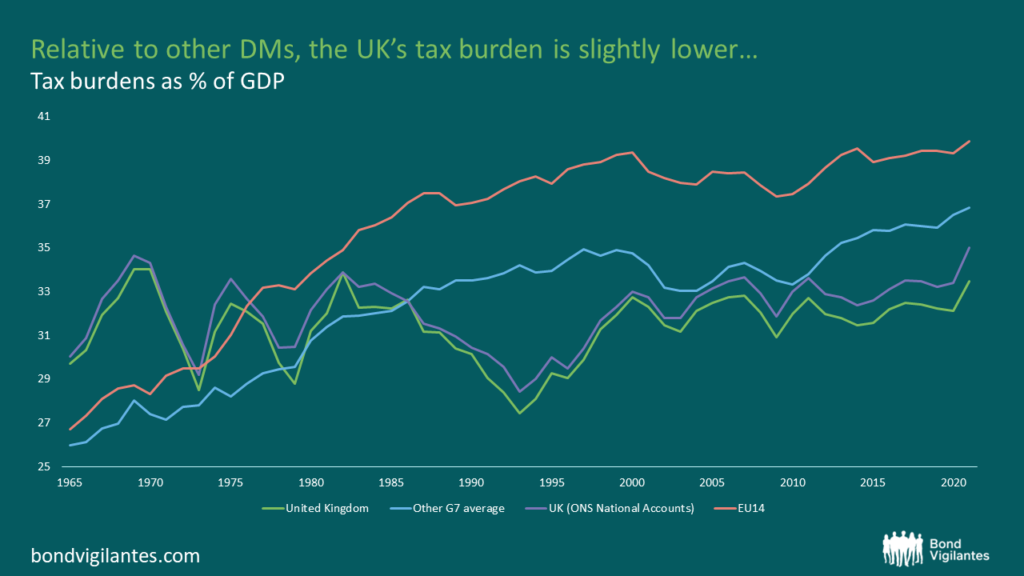

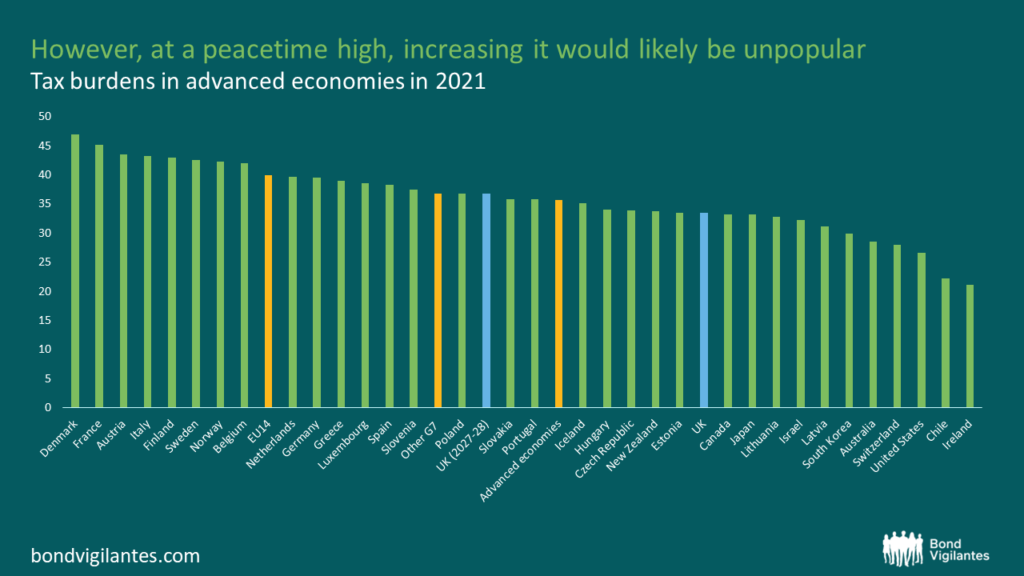

The chart below compares the UK’s long-term tax burden to other countries. Clearly, the UK is below some of its peers, suggesting there is scope to increase taxes. However, the level is currently at a peacetime high. It’s difficult to see taxes going up meaningfully from here. Let’s assume we are at or close to the maximum tax-generating point. Increasing tax revenue from here runs a real risk of slowing the economy further and is likely politically unpopular. Unless a tax increase is met with a meaningful improvement in Government services, it will be met with hostility. Equally, cutting taxes to spur growth is similarly difficult. We saw what happened when Kwasi Kwarteng tried to cut taxes to stimulate growth. The aptly names bond vigilantes were out in force and swiftly ended that agenda as investors lost confidence in the UK economy. Future Governments are going to be forced to demonstrate fiscal responsibility.

Source: OECD (March 2023)

Source: OECD, OBR (March 2023)

Debt interest

The various reasons for increasing debt interest payments have been discussed previously, but let’s take a minute to look at the various pressures here.

The chart below shows a long-term debt projection under various scenarios from the OBR; what is clear is that it’s going up, not down, under all scenarios. In fact, the OBR has projected that issuance for the next 5yrs is projected to be £1.1 trillion. That is almost half the entire stock of outstanding debt. Who is going to buy it, and at what level?

Source: OBR (July 2023)

Interestingly, the UK has the benefit of having the longest average debt maturity profile, amongst developed nations, of circa 14yrs. This means that rolling over debt at higher interest rates will take longer to feed through relative to a country that has a lower average maturity profile, like the US, which is circa 8yrs—a slight positive in that respect. However, the makeup of this debt is also important.

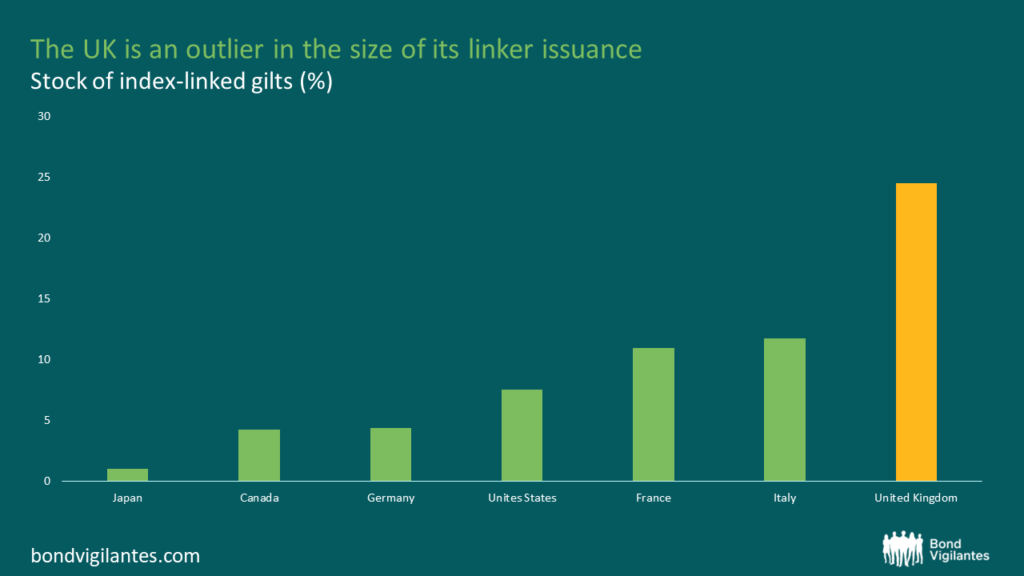

Inflation will erode debt as nominal GDP grows and existing outstanding fixed debt becomes smaller as a percentage of GDP. This can be a positive for those with a high proportion of fixed debt and an extended debt maturity profile. However, the UK has a relatively large proportion of inflation-linked debt as a percentage of total debt. As a result of inflation, the debt interest cost of inflation-linked bonds will rise in tandem, limiting this benefit. The UK has circa 25% of its debt linked to inflation, whereas Germany and US have circa 5% and 8%, respectively.

Source: Bloomberg (August 2023)

The UK’s Debt Management Office has made meaningful inroads in reducing this weighting over the last few years, but more needs to be done to limit the impact on debt interest payments when inflation spikes. The issuance of index-linked bonds can be a double-edged sword. If you issue index-linked bonds, you send a message to investors that you are serious about controlling inflation. If not, the opposite can be true.

However, if you have issued a high proportion of index-linked bonds and inflation materialises, the Government does not have the benefit of inflation eroding the debt stock.

Conclusion

The UK Government’s debt interest payments are poised to rise in future years to worrying levels due to factors such as rising debt levels, interest rate increases, and inflationary pressures. This will undoubtedly weigh heavy and Government will face severe challenges in managing its fiscal priorities while servicing the ever growing debt. Striking a balance between addressing the debt burden and supporting economic growth will be critical for policymakers in the coming years.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.