The Debt Reaper

Debt is an integral aspect of modern economies and has long been hailed as a catalyst for growth. When wielded judiciously, it stands as a potent tool for economic development, providing the means to finance projects, expand operations, and invest in essential sectors like education, health, and housing. In the right context, debt fuels economic growth, creates jobs, and fosters innovation. Furthermore, during economic downturns, it offers a safety net for individuals and organizations, helping them weather financial storms.

Source: GettyImages

The ghost of future wealth

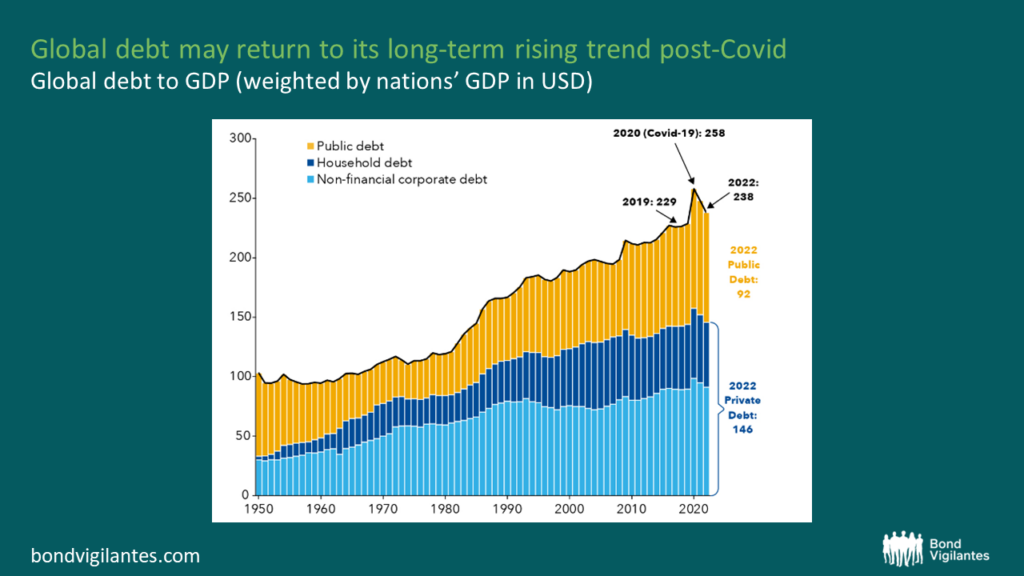

Governments have traditionally argued that as long as debt remains manageable and serviceable without difficulty, there’s little cause for concern. While this notion holds some truth, the reality is that recent growth has largely been fueled by an insurmountable increase in debt. Particularly since the Global Financial Crisis of 2008, the creation of what seems like wealth has resulted in soaring asset prices, including equities and real estate, contributing to an alarming rise in wealth inequality. However, there exists a disconnect between perceived wealth and actual wealth, a scenario unlikely to endure. Distinguished economists have persistently argued that debt for consumption essentially borrows demand from the future. This borrowed debt inevitably must be repaid, heralding a probable future slowdown in demand. However, debt allocated for investment purposes differs significantly, capable of fostering future growth and potentially curbing long-term debt.

Source: IMF (2022)

The trajectory of global debt, as depicted in the chart above, illustrates an unrelenting rise in both government and private debt over time. Up until the 2000s, the surge in debt was primarily attributed to burgeoning private debt, empowering a substantial improvement in living standards, especially in developed nations. Since 2000, private debt has plateaued, whilst government debt has sharply ascended, sustaining the growth in living standards. Yet, the overarching question remains – at what cost? However benign they might seem, debt levels can swiftly move from being a seemingly manageable concern to a formidable challenge once they surpass a particular threshold.

Renowned economists Reinhart and Rogoff attempted to ascertain this threshold and concluded that it begins to matter when debt levels hit 90% of GDP. Nonetheless, this figure remains a moving target, contingent upon a multitude of variables. Recent economic theories, particularly Modern Monetary Theory, have further complicated this limit, challenging the traditional understanding of debt thresholds. The struggle to identify this threshold arises from the confluence of two pivotal variables: the stock of debt and the level of interest rates, both in perpetual flux. Research aiming to determine at what point servicing debt becomes unmanageable largely predates the widespread implementation of quantitative easing and the drive towards zero interest rates. As a result of these two relatively recent phenomena, debt levels have significantly swelled, accompanied by a notable surge in bond yields in response to this. Some nations like Japan, sustaining an elevated debt level of 250% of GDP, continue to flourish due to their substantial savings, but issues are beginning to surface. The Japanese economy represents a unique case. Conversely, smaller economies running twin deficits are anticipated to confront their threshold much sooner. Though the definitive threshold remains an mystery, it is evident that we are closer to this limit than we were just a few years ago. Perhaps economies with low levels of outstanding debt will be considered the new safe harbour going forward.

The Factors that Transform Debt into a Menacing Problem

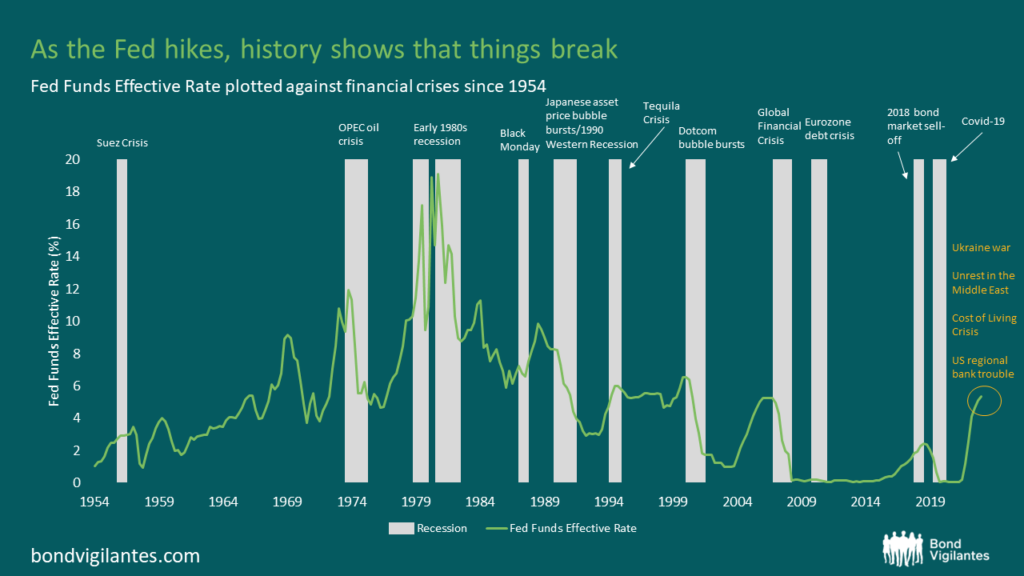

Interest Rates:

The escalation of interest rates significantly affects debt servicing costs. As rates soar, the cost of servicing this debt climbs, straining government budgets and impeding economic growth. The Federal Reserve and other central banks strive to engineer a controlled economic slowdown to contain inflation. Nevertheless, history often demonstrates that rapid interest rate hikes are typically followed by recession.

Source: Bloomberg, M&G (November 2023)

Crowding Out:

The hike in rates leads to a natural consequence called crowding out. As rates rise, investors lean towards guaranteed government bond yields rather than venturing into riskier private sector investments. This shift diminishes the availability of private sector financing and forces down valuations of private assets, adversely impacting the equity market. On the consumer front, higher interest rates stimulate a proclivity for saving, as consumers take advantage higher returns in cash, but also brace for anticipated higher tax levels in the future. This hampers demand and augments the likelihood of an economic downturn.

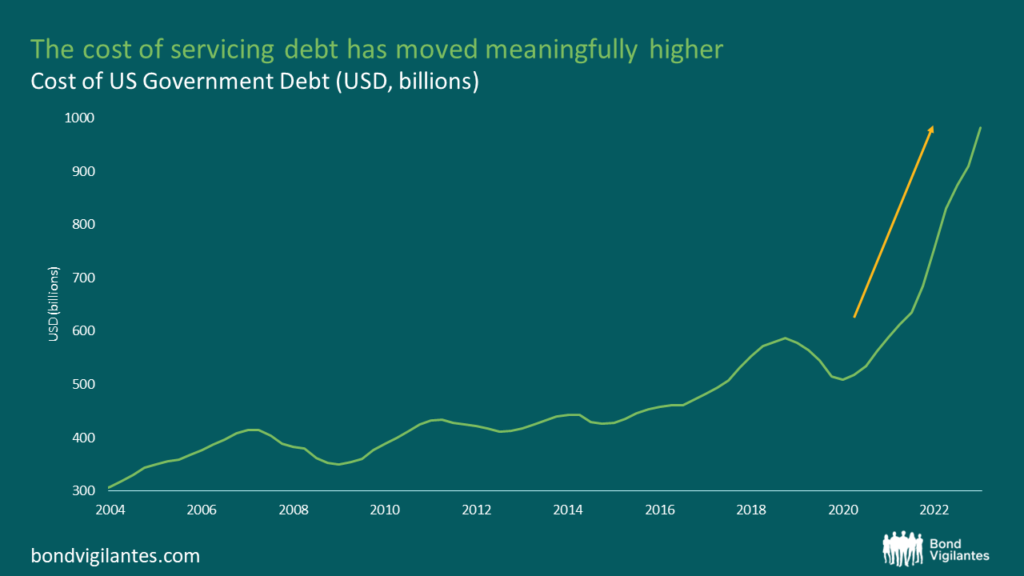

Budgetary Constraints:

When a significant portion of a government’s or a business’s budget is directed towards servicing debt, it limits the resources available for essential services, investments, and initiatives. It also restricts the government’s ability to implement a Keynesian fiscal stimulus during economic downturns.

Economic Downturns:

Economic recessions or crises can exacerbate debt issues. Reduced revenues and amplified demands on government services lead to deficits and increased borrowing requirements. Extended periods of ultra-loose monetary policy invariably breed misallocations of capital. The rapid increase in interest rates will likely bring these misallocations to the surface, albeit with the usual monetary policy lags. A slowdown is more probable than not.

Investor Confidence:

The current high levels of global debt have notably diminished investor confidence. If creditors lose faith in a government’s ability to manage and service debt, they will demand higher yields to cover risks. Alternatively, investors might abstain from investing altogether or, worse, decide to sell existing debt, further complicating the situation.

Battle lines drawn – electorate vs bond market

Governments often bear the brunt of public anger, seen as the ‘bad guys’ for imposing spending cuts and increased taxes. However, this essentially reflects the democratic process, where elected governments serve as gatekeepers of fiscal policy. Should the electorate resist upcoming austerity measures intended to foster debt sustainability, they will likely opt for a new government. However, this poses a challenge. The electorate’s choices for fiscal largesse have been feasible thus far due to low debt levels, compounded by the era of ultra-low interest rates. The bond market presses for fiscal rectitude, pitted against an electorate reluctant to endure forthcoming difficult times in pursuit of debt sustainability given the context of a painful austerity experience in the not too distant past. The recent government bond crisis in the UK is a very good example of this issue and ultimately the bond market won. Further struggles between the bond market and the electorate loom on the horizon.

In the case of the United States, achieving debt sustainability appears challenging. Both major political parties seem at odds in their fiscal ideals. Democrats aspire to expand entitlement spending, while Republicans are inclined towards tax reductions. Under both administrations, fiscal deficits continue and debt mounts. Ongoing events in regions like Ukraine and the Middle East are unlikely to conclude soon, adding to US military spending, and increasing the debt burden. The move towards carbon neutrality will continue to compete in the race of ever increasing spending. The US is not alone in facing these issues, however, if the biggest and most liquid bond market in the world runs into difficulty, the impacts will be felt far and wide.

Source: Bloomberg (30 September 2023)

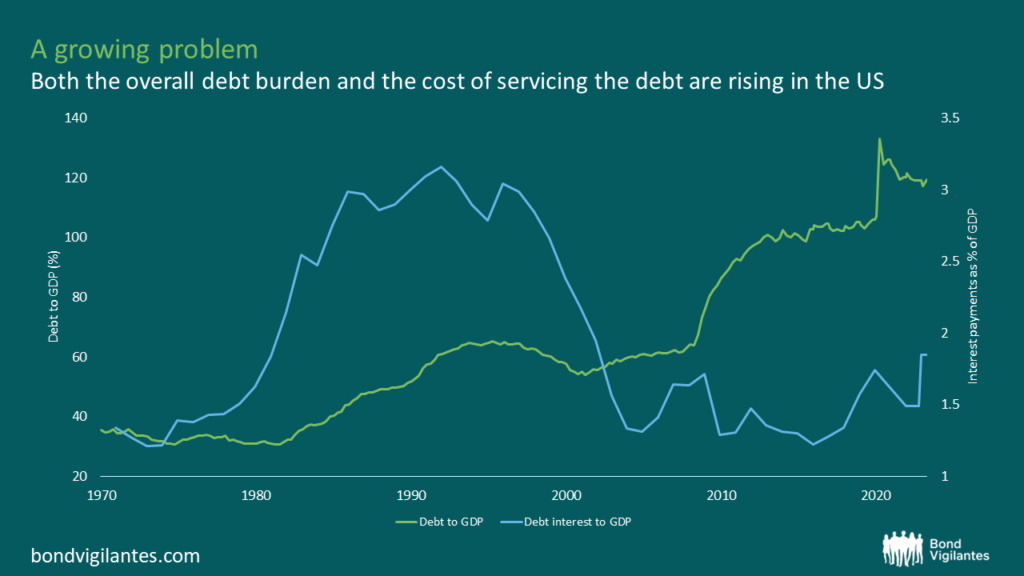

As it stands debt servicing costs remain relatively low in historical context. However, the Treasury market has an average maturity of circa 7 years and approximately 31% of the $33 trillion needs to be refinanced in the next 12 months, which will result in debt servicing costs moving meaningfully higher. The below chart shows what the Treasury has experienced to date.

Source: Bloomberg, St Louis Fed, M&G (April 2023)

The whims and trends in bond markets offer insights into current sentiments, while elections present an accurate pulse of the electorate’s leanings. The impending number of elections over the coming year hints at potentially increasing political instability.

Source: Bank of America

Nassim Nicholas Taleb famously introduced the black swan theory, identifying events that emerge unexpectedly and bear significant consequences. In contrast, a neon swan characterizes rare yet highly predictable events with severe implications. The burgeoning stock of debt firmly falls into the latter category.

A tussle between the electorate and the bond market is unfolding. The eventual victor remains unclear, but the debt reaper is sure to claim some economic souls along the way.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.