The Carousel of Confusion

With The Barbie Movie beating both Oppenheimer and Super Mario Bros to the top spot as highest grossing film of 2023 (a cool $1.4 billion), I feel justified in drawing from one of its antecedents, Barbie Mermaidia. Prince Nalu (goodie) leads the Fungi (baddies) into the Carousel of Confusion, a hypnotic whirlpool where one loses all sense of direction, in an attempt to thwart their evil intentions. As a metaphor for both economics and markets through the past 12 months, this seems pretty on point, as little to nothing has gone to according to plan and I am as confused as I was a year ago about the long term outlook for inflation, rates, growth and debt. The star on the top of this particular tree is the weakening of the past forty years geopolitical order – peace for growth – which might end up costing us more than just higher prices on our smartphones.

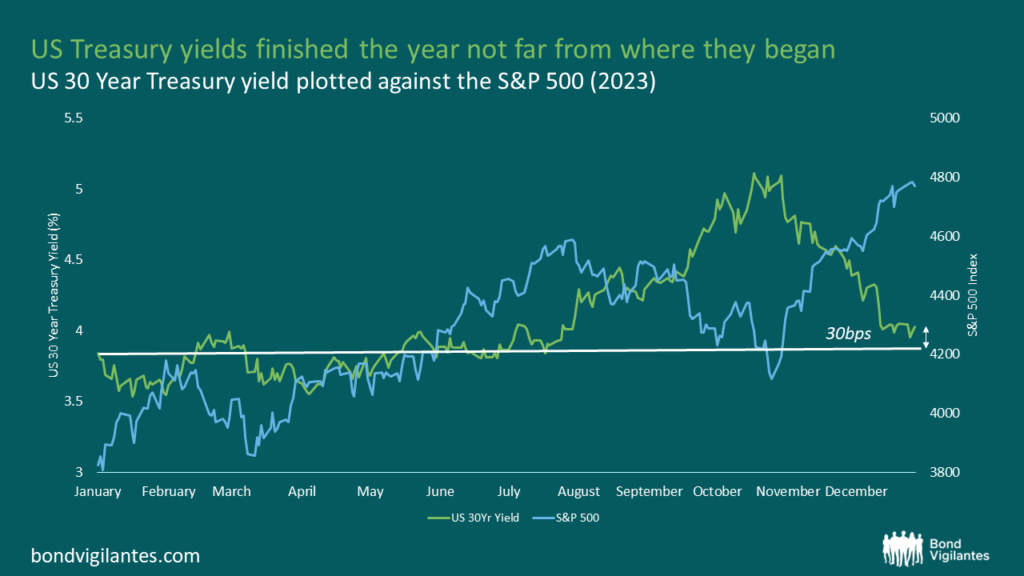

What’s more, if you’d taken a 12 month sabbatical through 2023, spent on a desert island listening to the Smiths and the Velvet Underground, then upon firing up your Bloomberg on New Year’s Day, what would be most surprising of all, is that none of this uncertainty is visible in markets. US long bond yields are just 30 basis points above where they were at the end of 2022, and the US equity market is reaching new highs. Does this make any sense?

Source: Bloomberg, M&G (31 December 2023)

There have broadly been two schools of economic thought about what has been going on and the market is now betting largely on one of them. In the red corner we find Larry Summers, he of Secular Stagnation fame, who vehemently argued the post-Covid inflation surge was all about the American Rescue Plan, cheques (funded by printed money) dropping through mailboxes whilst people sat at home playing video games and reading War and Peace, allowing them initially to save the money and then splurge it all when the shops re-opened. Conclusion – inflation is primarily demand-driven and applying a standard Phillips curve framework (the inflation/unemployment trade off), to get inflation down would require enough rate hikes to push the economy into recession with the accompanying rise in unemployment. The US Federal Reserve had clear sympathy with this line of thinking, repeatedly raising concerns about inflation and between March 2022 and August 2023 hiking rates by 525 bps, to tell everyone they were serious about not letting prices get out of control. Through all of this the US labour market was lava hot, with around 10 million unfilled vacancies and unemployment at or close to multi-decade lows. The desire to inflict some economic pain motivated rate hikes, not because Fed governors are bunch of macroeconomic sadists, but because low and stable inflation is seen as the cornerstone of long term growth.

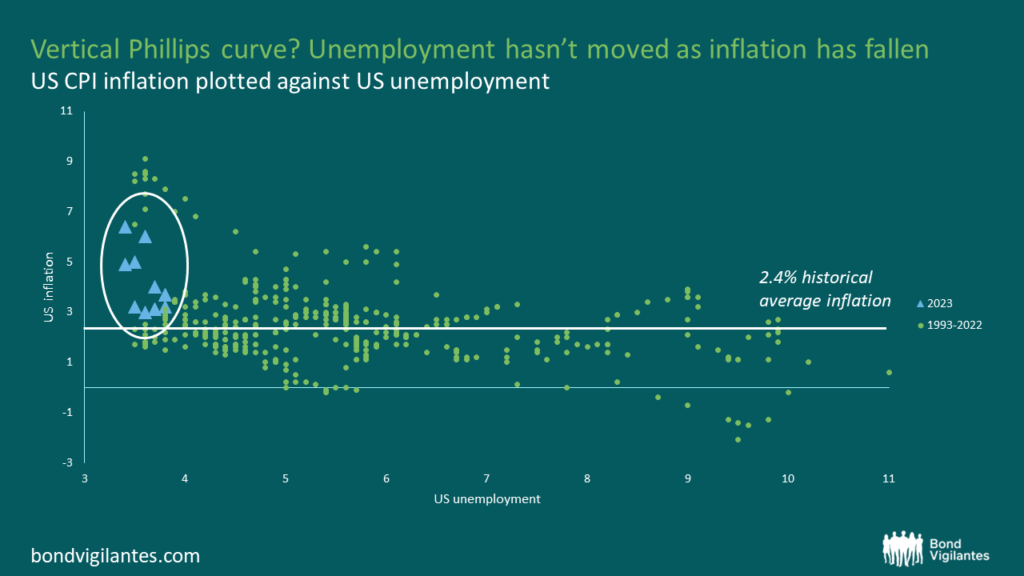

In the blue corner, we have Claudia Sahm, a former US Fed economist and Obama economic advisor, who took an entirely opposite view – that inflation was essentially about Covid supply bottle-necks exacerbated by a Ukraine gas/grain global price spike. In this telling of the story, the Rescue Plan was critical to stablishing demand during and after the Covid pandemic, but it had little impact on underlying inflationary dynamics. Her view is expanded upon in a recent Financial Times interview (Claudia Sahm: it’s clear now who was right). Empirically, inflation has fallen from a peak of 9% to 3% and unemployment hasn’t budged, which would suggest that the Phillips curve is currently vertical. De facto, there was no need for job shedding or recession for inflation to come down. Of course, the 10 year pre-Covid average rate of inflation is 2.4%, and the US isn’t back there yet and core CPI (ex food and fuel) is still running at 4%, but Summers has had his nose properly bloodied and has been busy of late eating some humble pie (see his FT interview here: Larry Summers: we haven’t nailed the landing yet)

Source: Bloomberg, M&G (31 December 2023)

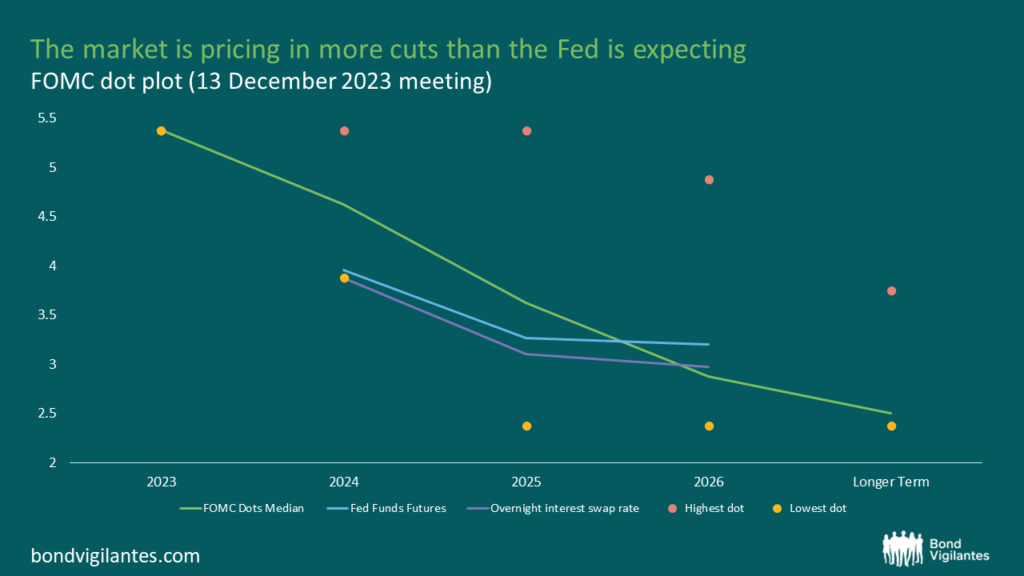

Wading into this ring, in an rather extraordinary turn of events, is Jerome Powell, Chair of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve. At the December meeting Powell performed perhaps the most material volte face since Boris Johnson abandoned the bendy bus, announcing essentially a view that inflation was beaten and rate cuts were coming.

In truth, no one knows what’s happening because there is no prevailing macroeconomic theory which is capable of explaining the inflation, growth, unemployment and rates dynamics that have been experienced in the past two years. Sahm herself, when asked what theory should be applied in these circumstances, answered “common sense”, which I doubt would get you a first at the LSE, but does at least capture the fact that what has occurred might require a quick call to Mulder and Scully rather than J Powell or Andrew Bailey. Which all leaves me cold when it comes to suggesting that it is a good time to bet the house on the view that inflation is beat, and yet that appears to be exactly what the market has done. Powell’s ‘Dot Plot’, showing the Fed’s own expectations for rates going forward, indicates 3 cuts in 2024. The market is already banking on 6. Sahm is doing backflips whilst shouting ‘I told you so’.

Source: Bloomberg (13 December 2023 meeting)

Of course, you never know in investing, so 6 could be right or even conservative. Covid being the first global pandemic since Spanish Flu a hundred years ago, provides little to no help in terms of historical calibration, so perhaps it isn’t surprising that markets feel ungrounded. A couple of months of weak high-frequency data and a recession is on the cards, one poor inflation print and all hopes for rate cuts are dashed. With no bedrock to anchor to, markets are highly likely to remain volatile in response to data and deploying substantial portions of available risk budgets to backing this view doesn’t feel well rewarded. US bonds have already rallied 100 bps, that’s a 15% capital return on the 30 year bond in just six weeks, almost exactly the same as the S&P 500 from its end October low. US Investment Grade credit now trades at a spread of just 100 bps over government peers and US High Yield at 340 bps, both within earshot of their lows for the last decade. In equity land, the S&P 500 is sitting at 3.9x price to book 12 months forward. These valuations hardly represent a dripping roast in terms of opportunity. A lot has to go right for these numbers to make sense. I would add that in my 30 odd year investment career, this would be the first monetary cycle of such ferocity and magnitude that didn’t provoke some cracks somewhere to open in the global financial system.

To add weight to this call for a pause for thought, the IMF released a paper in September last year titled 100 Inflation Shocks that examined common features to 100 separate inflationary episodes, tracking data 5 years prior and 5 years after the shock. Oddly, to my mind, given its potential relevance to current circumstances, it got almost no airtime. In my former role as CIO of M&G Southern Africa, I attended a meeting of the South African Reserve Bank where one of the authors of the paper was invited to present, so some people have sat up and paid attention, but perhaps Mr Powell and the market know better.

The paper identified 7 stylised facts from the data and the second of these has particular relevance now, that almost all of the episodes that were not resolved within 5 years involved “premature celebrations”. That is to say they experienced initial sharp declines in inflation that led them to believe the job had been done, only to find inflation re-accelerated or plateaued at a higher level than pre-shock. It seems an entirely reasonable question to ask if the expected Fed easing this year will in time prove to have been premature. Statistically, unresolved episodes accounted for 45% of the total in the paper, so it has happened often in history (and not just to wayward Emerging Markets either).

The third fact that I’ll end this discussion on for now, was that successful inflation resolution had substantially higher real rates than unsuccessful ones. US real Fed funds, using current CPI as the deflator, only went positive at all in April 2023, having been highly negative since mid-2020 when inflation began to accelerate. If the Fed starts cutting, and certainly if it cuts as much as the market expects (6 times), little of the current positive real rates will be left. This won’t matter if Sahm is right: that the common sense theory of inflation is all there is now, that it has been an entirely transitory phenomenon and underlying inflation expectations held by all economic agents haven’t shifted one iota. This will then be an economic miracle of Biblical proportions. Sadly, like Thomas, I’ll believe it when I see it. For now, I remain firmly in the carousel of confusion and markets need to offer substantially better odds than they are in order to throw lots of risk at them.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.