The Traitors – can a game of human psychology draw parallels with bond markets?

After last week’s final of the second series of ‘The Traitors’, I have had endless conversations about the human psychology behind the decisions made; how the show could be a reflection of many elements of our society; and about how winning the game requires the most delicate balance of popularity, strategic thinking and perfect timing. I also couldn’t help thinking about how the show links to bond markets and behavioural finance when thinking of some of the shows’ key themes – herd mentality; deviating from the status quo; and how a lack of information can easily lead to sub-optimal decision making.

For those unfamiliar with the show, 22 contestants, known as ‘faithfuls’, arrive at a castle in Scotland. Upon arrival, some are selected by host Claudia Winkleman to play the game as ‘traitors’.

Both faithfuls and traitors participate in group challenges to increase the prize money. The faithfuls must work out who among them are the traitors and banish them before the end of the game. If the faithful succeed in identifying the traitors, they win the money. However, if any traitors make it to the end of the game, they walk away with the prize fund.

AI Generated photo

Simple? Not quite – the traitors meet every night to pick a faithful to murder. Everyone gathers round a table to discuss whom they suspect is a traitor and why, then vote on whom to ‘banish’, eliminating that player from the game. However, by revealing whom they suspect, they make themselves susceptible to murder. The traitors can recruit other traitors along the way, and most importantly – they can also turn on each other.

The game is very similar to an earlier concept developed by the Russians in the 80s, known as ‘Werewolf’ or ‘Mafia’ – but they use terms like ‘villagers’ and ‘werewolves.’ The concept was invented by a student of sociology, who wanted to prove the premise that an uninformed majority will always lose a battle of information against an informed minority.

We can draw parallels between the dynamics of The Traitors and the functioning of bond markets. Just as in the game, where an uninformed majority is susceptible to manipulation, in bond markets, investors without adequate information may make suboptimal decisions.

Let’s focus on a few key themes:

Information Asymmetry

In the game, some players possess hidden roles, creating information asymmetry. In bond markets, there is often a lack of perfect information about future economic conditions, monetary/fiscal policy implementation, geopolitical events and central bank decisions, to name a few. Sophisticated investors actively seek and analyse information to gain an edge, similar to players in the game who gather clues to uncover hidden roles. Active investors employ comprehensive research, data analysis, relative value analysis and issuer engagement to identify mispriced bonds or try and predict market movements. If we’re talking about season 2, I reckon Jaz (aka Jazatha Christie) would have the best chance at identifying mispriced opportunities in our world. I’m not sure I’d be buying Zack’s fund.

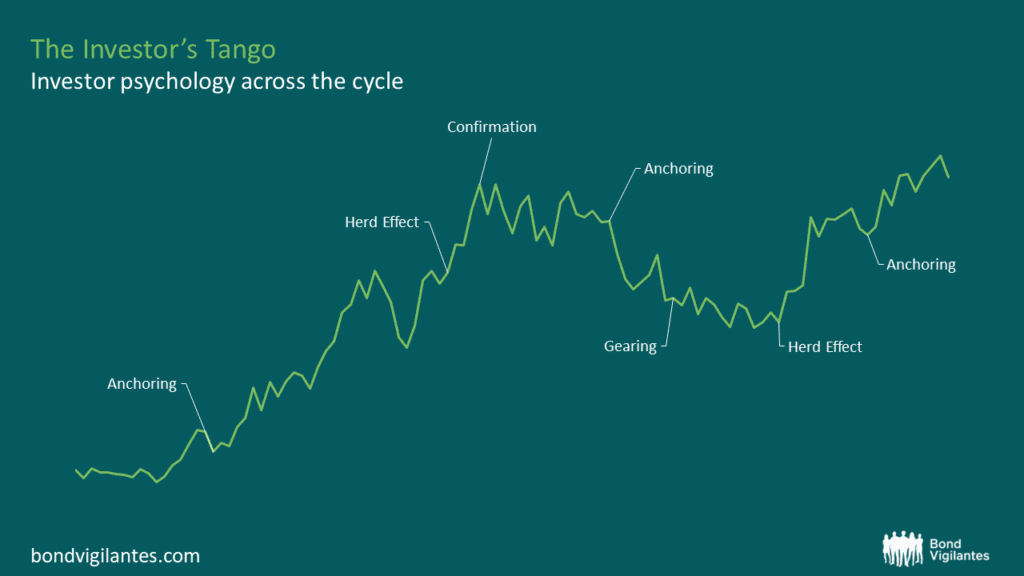

Behavioural finance recognises that individuals may exhibit cognitive biases when processing information – asymmetry can be exacerbated by biases like overconfidence, anchoring or confirmation bias. It also recognises that markets are not always rational, hence asset prices can be driven by investor sentiment, capital flight and herd mentality. Investors must navigate their own behavioural biases and those exhibited by markets, using disciplined analysis and objective decision-making. This mirrors the challenges faced by players in the game when processing clues based on personal biases and emotions, and where irrational decisions based on incomplete or misinterpreted information can influence voting patterns and game outcomes.

Source: Adapted from CentralCharts.Com, Author: Vincent Launay, as at 01.02.2024

On the issuer side of things, asymmetric information can occur in any situation involving a borrower and a lender. Lenders will charge a risk premium to compensate for a disparity in information, but unsecured loans can be costly – for example, if a borrower fails to disclose negative information about their financial state, or simply fails to anticipate a worst-case scenario. One could also argue that a borrower’s choice of debt maturity depends on private information/predictions of their own default probabilities – that is, borrowers with favourable information may prefer to issue short term debt, while those with unfavourable information/more uncertainty may prefer to issue longer term debt. Lenders demand additional compensation for the risks associated with longer dated debt, hence the typical upward-sloping yield curve.

Game Theory and Herd Dynamics

In the Traitors, there are many instances where we see herd mentality manifest itself, whereby players have little incentive to deviate from the decisions of the majority – doing so would risk attention being drawn to themselves. This may also lead to players blindly voting based on popular opinions that have been planted by traitors themselves, risking falling victim to manipulation by a savvy minority.

In game theory, the concept of Nash equilibrium points to a scenario where no investor can improve their position by changing strategies, if others remain unchanged. In reality, however, markets show strategic interplay among active participants, whereby investors anticipate the reactions of others to economic indicators or central bank decisions, and adjust their portfolios accordingly. We also see this within central banks themselves, whereby there is often little incentive for central banks to be outliers when it comes to monetary/fiscal policy, with the risk of isolating their currencies or hindering investment flows (of course it does happen though – take the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) or the Bank of Japan (BOJ) as current examples of major outliers).

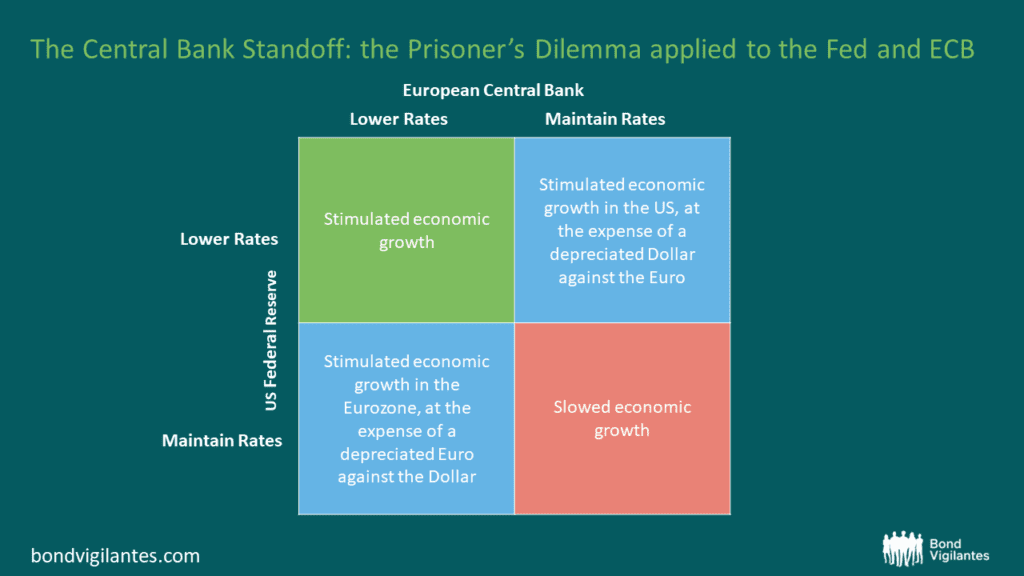

This can be observed with the European Central Bank (ECB) and the US Federal Reserve (Fed), in their decision to lower rates or maintain them at current levels. The payoff matrix below represents the outcomes of these choices and identifies two Nash equilibriums – when both banks simultaneously lower rates (leading to stimulated economic growth), or keep them the same (resulting in a possible global economic slowdown).

Source: M&G

This illustrates that the globally optimal outcome could be achieved through a collaborative effort between the ECB and the Fed. However, the fear of non-cooperation, given the potential for currency depreciation in the event of unilateral lowering, might lead to both maintaining rates – a less favourable scenario, but a Nash equilibrium nonetheless.

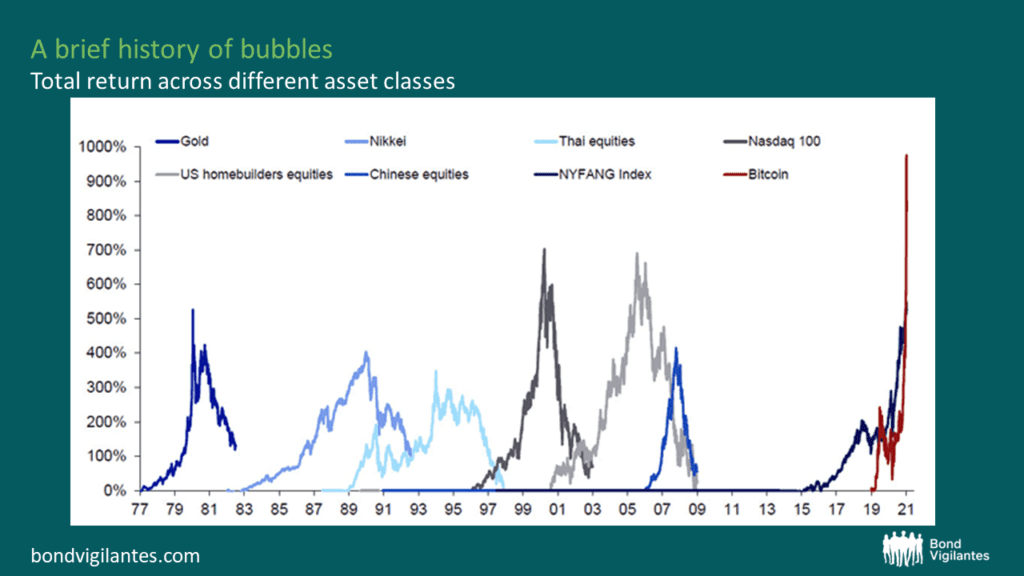

We all know how herd mentality can manifest itself in bond markets, leading to market bubbles, panics, or exaggerated price movements. What happens is investors follow prevailing market sentiment without conducting thorough independent analysis. In these situations, it is the informed minority that prevail and outperform the broader market, deviating from the crowd and making contrarian bets based on well-reasoned analysis.

The role of regulators

There are of course regulatory challenges associated with managing phenomena like herd behaviour, including potential risks to market stability and the difficulty of identifying and mitigating collective irrationality.

Financial regulators act as a governing force in the economy, just as a game moderator (Claudia) guides the narrative in The Traitors. Of course, regulators are there to ensure vigilance, transparency and fair practices, and thus protect participants from market manipulation by informed minorities.

We saw this in extremes in the Global Financial Crisis, where an informed minority misrepresented sub-prime debt – including products being extended to borrowers buying bubble-priced homes that were beyond their means – as highly rated securities. Of course, there are those who did their homework, became informed and were able to avoid the subsequent collapse in financial markets as the bubble unravelled, but broadly this is a classic example of asymmetric information, herd mentality and the need for regulatory responses.

Source: Deutsche Bank, Bloomberg

To sum up, I could go on for pages and pages about the parallels between human psychology in The Traitors and in financial markets, but it serves as a reminder to stay vigilant, resist herd mentality, and emphasises the importance of thorough research, strategic decision-making and robust regulatory frameworks.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.