100 Days of Milei

As Franklin D. Roosevelt took to power in 1933, the USA had just entered the fourth year of its Great Depression. Faced with such significant economic turmoil, Roosevelt had little choice but to begin implementing structural reforms within a very short timeframe, not just to galvanize the economy, but also to stamp his authority having just been elected to his country’s greatest position of power. Thus, the concept of a president’s ‘first 100 days’ was born.

Javier Milei, Argentina’s newly elected president, shares similarities with Roosevelt in that he has inherited, to put it mildly, a struggling economy, and has begun attempting to implement reforms in very quick order. However, unlike the Great Depression, Argentina’s economic issues did not follow a boom, with the US at least benefitting from the roaring ‘20s prior to its bust.

The country’s current environment, alongside its history of economic mismanagement, marked by defaults and more recently bookended by the Peronist movement, poses significant challenges for Milei. Now that 100 days have passed since Milei’s ascension to the presidency, and with his statement that there will be no room for gradualism and that shock therapy will be required, we can take a first look at the promised economic revolution.

The Burden of Overspending

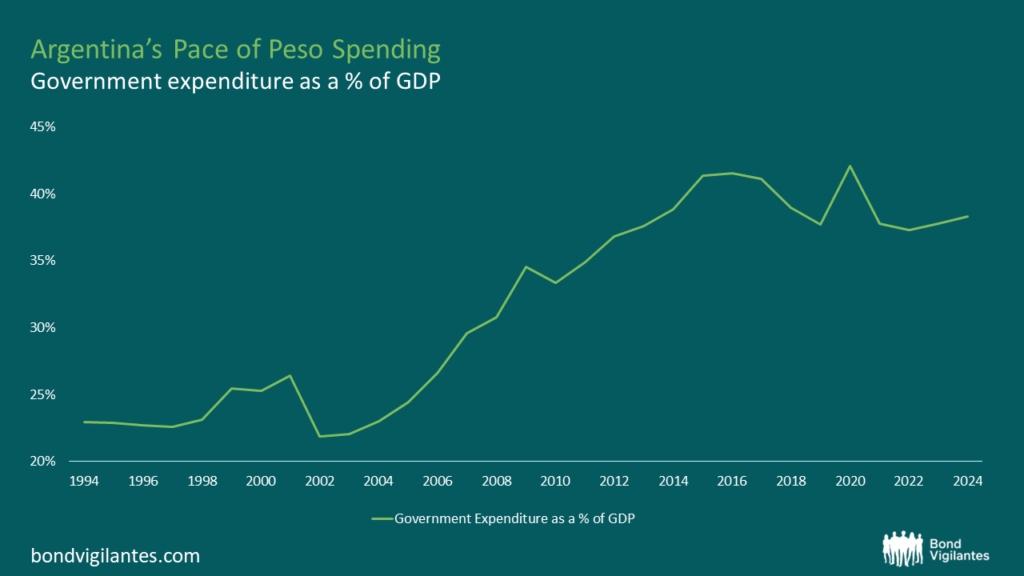

To try to understand where we are today, we should briefly consider Argentina’s history and focus on a common issue that Argentina has faced over many periods: its spending problem.

The below chart highlights the extent to which government spending as a percentage of GDP has increased since 1994. Under normal circumstances, the line’s upward trajectory over time would not necessarily translate into a precarious situation with many neighbouring countries maintaining a similar ratio, if not higher. Other countries achieve this through more effective fiscal management and a more robust economy. However, Argentina is a special case.

Source: M&G, Bloomberg as at January 2024

Between 1994 and 2022, Argentina embarked on a number of fiscally expansionary programmes, albeit these were somewhat restricted during the 90s due to the expensive currency convertibility regime with the US dollar. These programmes were often punctuated by periods of austerity, yet a balance was never really achieved. Government spending increased markedly, mainly through borrowing, which led to budget deficits and an increasing public debt pile. Despite this, revenues and economic growth never caught up, failing to allow for deficits or borrowing levels to be reduced.

Instead, typical outcomes were periods of crisis, a devaluing peso, and economic instability. These cycles added to concerns that inefficient public services, corruption, and unsustainable social programmes were never going to allow Argentina to develop in a sustainable manner via a disciplined approach.

But, history tells us that Argentina has, at times, struggled to enact sustained fiscal discipline.

Don’t Cry for More Money, Argentina

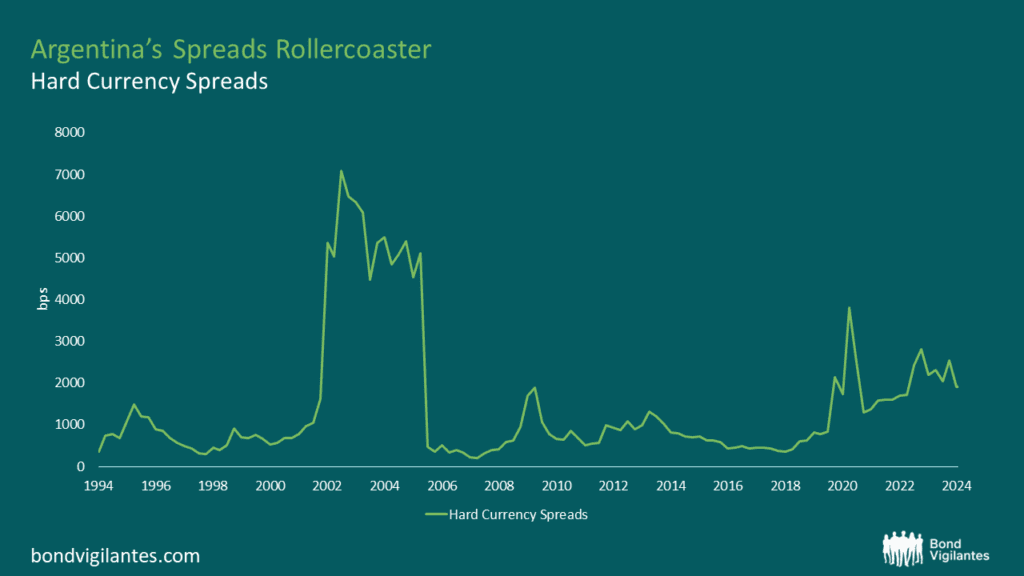

The below chart highlights periods of severe spread widening, which paints a pretty pessimistic picture of the country’s sovereign debt, as well as expectations for Argentina’s ability to service that debt. Over the period, spreads averaged c. 1,400bps, a figure well within distressed territory. The seesaw trend suggests that even as the country recovered from one crisis, they were not far away from another.

Since 1827, Argentina has defaulted on its sovereign debt nine times. Many of these defaults were driven, in part, by the holy trifecta of fiscal mis-management: spending too much, borrowing too much, and taxing too little.

Source: M&G, Bloomberg as at January 2024

Argentina also holds the unenviable distinction of the largest sovereign default on record, standing at $95 billion in December 2001. Leading up to this, the holy trifecta was in full swing between 1994 and 2001, with government spending increasing by an annualized rate of 2.67% and borrowing levels increasing by an annualized rate of 9.09%.

The increase in spending could have been sustainable had government revenues also risen; however, with GDP growth stagnating over the period and an annualized growth rate of just 0.61%, tax receipts were restricted. What proved even more unsustainable was the continued growth in borrowing levels, particularly given that much of this was predicated on borrowing from one hand to pay back the other.

The two hands being the IMF and foreign investors. The continuous doom-loop of borrowing from the IMF to satisfy lenders was worsened by significantly deteriorating sentiment and worsening economic conditions during the preceding period, which began to reach its crescendo in the late 1990s. As Argentina borrowed more, the cost of borrowing increased, the more Argentina paid back, the less they had to spend, and the less they had to spend, the more they had to borrow. Sadly, this only ended once the IMF belatedly stopped lending to Argentina in 2001.

As of the end of 2023, the Argentinian economy is once again facing severe difficulties. With year-on-year inflation exceeding 200%, the central bank’s policy rate at 100%, and an exchange rate surpassing 800 to convert Argentinian pesos to the US dollar. This isn’t a particularly conducive environment for the government to maintain a functioning economy, one not overly reliant on borrowing or spending, and where revenues are able to grow.

Milei’s Political Melee

Milei’s campaign was nothing short of a rollercoaster. The chainsaw wielding economist promised to “blow up” the central bank, adopt the US dollar, and cut ties with any country he deemed as socialist (including Lula’s government in Brazil, which also happens to be Argentina’s largest trading partner).

Adopting the dollar does have some merits – Ecuador has done so which has provided elements of stability – but Argentina and the dollar have not always gone hand in hand. The previously maintained convertibility of the US dollar and Argentinian peso was one of many pressures that pushed Argentina closer to its 2001 default.

But, as we have seen since Milei came to power, the hyperbolic policies and extreme statements have been watered down. What we have seen over the past 100 days has been more pragmatic, orthodox, and fiscally aware than what could have been expected.

Despite this, his underlying themes have been maintained. Milei views socialism as one of the world’s evils and has acted to try to take the country off its welfare-centric life-support by going back to a more free-market approach, where capitalism rules supreme. Should his controversial “omnibus” reform bill make it to fruition the role of the state will be significantly reduced, state-controlled enterprises will be privatised, and spending will be cut dramatically with a zero-deficit being a non-negotiable.

Markets have seen Milei’s electoral victory, and subsequent reforms, as a positive. Since the results were announced on November 19th, sovereign bonds maturing in 2030 repriced from 29 cents on the dollar to 45 cents as at the time of writing. Sovereign spreads equally improved, tightening from 2,165bps to 1,704bps which, whilst still being priced firmly in the distressed territory, show signs of improvement.

Despite this, there is still significant work to be done, and success will be measured over years rather than months, and certainly not over a mere 100 days. There are still significant headwinds to navigate: unrest within the working-class population, poverty levels at an all-time high, and a lack of majority in congress; and markets can be notoriously impatient.

It stands to reason, however, that Argentina should be far greater than its current sum of parts. The country has an abundance of natural resources, as well as livestock, a geographical advantage to facilitate trade, and a highly educated workforce. These factors alone are not sufficient to drive an economy but can certainly support a growing economy when matched with a sensible fiscal policy and a more normalised monetary policy. However, what comes first is very much a dilemma shared by the chicken and the egg.

As with many things, patience will be an important factor in determining whether markets can become comfortable with Argentina’s latest push towards prosperity. But patience is a virtue, and even Roosevelt took six years to unshackle the might of the US from the grips of its Great Depression.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.