Bank M&A: A domestic affair?

In our last blog, “The best defence is a good offence”, we discussed the drivers behind the growth in European bank consolidation activity. Here, we explore how consolidation can benefit bank bond investors, and identify where further consolidation is most likely to occur. We start by considering European domestic markets before evaluating the potential for cross-border consolidation, which a number of European policymakers have publicly encouraged. Finally, we examine the US, assessing how last year’s regional bank crisis and possible regulatory changes may affect mergers and acquisitions (M&A) in that market.

Why consolidation can benefit credit investors

Following the Global Financial Crisis, we saw consolidation resulting from weaker banks being rescued. M&A is now more strategic, with different drivers, as noted in our previous blog post. We would argue that a healthy, but not excessive, level of consolidation creates a stronger banking system, benefitting bank credit investors. Banks in more consolidated markets tend to have additional scale, enabling more investment and reducing the likelihood of harmful pricing wars seen in more fragmented markets. The banks will also be more systemically important, facing increased regulatory oversight and focus.

Taking Ireland as an example…

Consolidation in the Irish banking market culminated with the exit of KBC and NatWest in 2022, leaving the top three banks (Allied Irish Bank, Bank of Ireland, and Permanent TSB) with a combined mortgage market share exceeding 80%. Permanent TSB, which saw its mortgage loan book increase by 40% with the Ulster (NatWest) loans acquisition, achieved an investment grade senior unsecured rating with Moody’s shortly after the combination, with Fitch following in 2024. It currently has its ratings on positive outlook with both Moody’s and S&P.

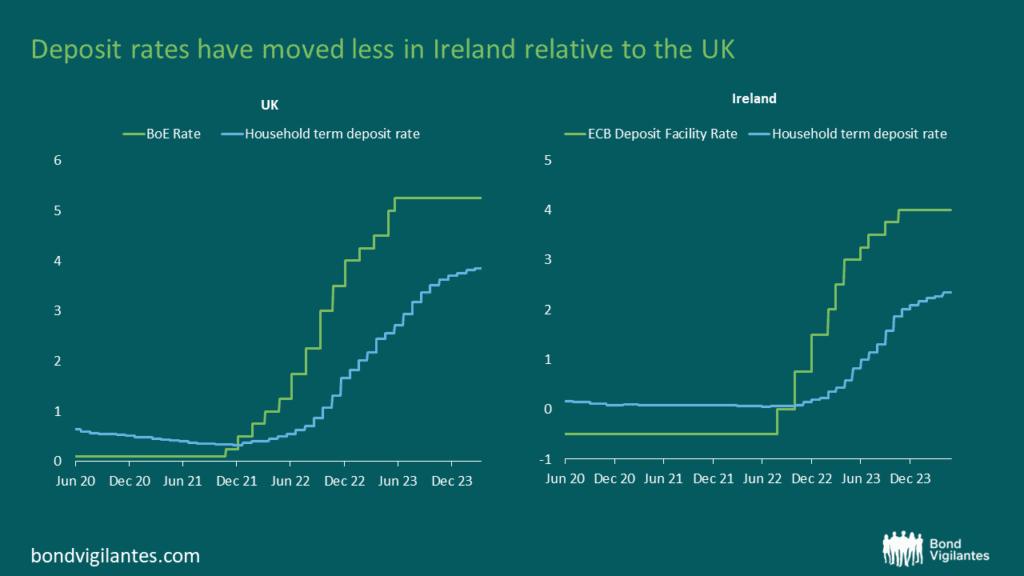

Although many factors contributed to the Irish banks’ rags-to-riches stories, including significant deleveraging in the economy, consolidation has played a part. It is also likely a reason why the Irish banks have passed on less of the central bank’s base rate increases to depositors than UK banks, which operate in a more fragmented market, thereby enhancing their profitability. However, the competitive landscape remains fluid, with new entrants like Spanish bank Bankinter, which already provides mortgage and consumer loans in the local Irish retail market, applying for a banking licence to offer local deposits.

Sources: Central Bank of Ireland, Bank of England (data to April 2024)

Where in Europe could we see more domestic consolidation?

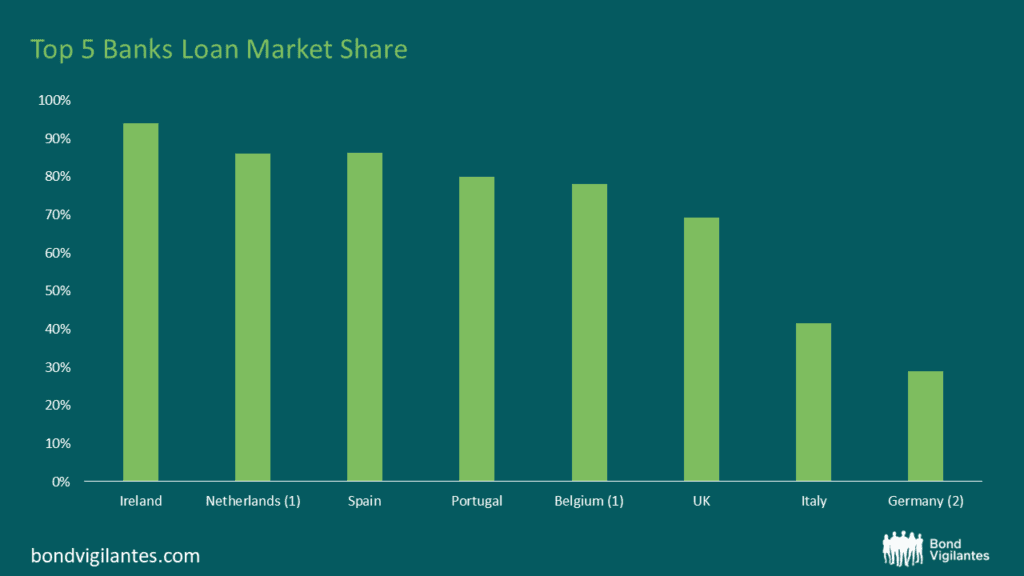

The chart below shows the varying degrees of banking sector concentration in Western Europe, with Italy and Germany among the least concentrated. We discuss the likelihood of consolidation in both of those countries as well as the prospects in other parts of Europe.

Sources: M&G, Company Reports, Central Banks, IMF, as at year-end 2023. (1) Based on banking assets. (2) Market share of the German privately-owned and listed banks (does not include savings banks or cooperatives)

Italy

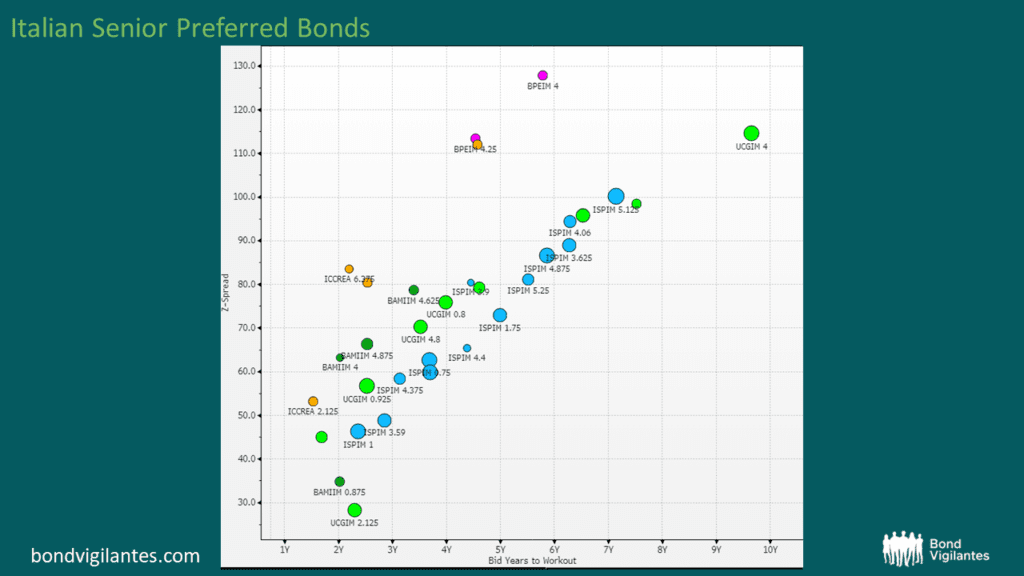

Italy is one region where we could see further consolidation. As seen in the chart above, banking concentration is relatively low in Italy. The Italian government has started a gradual sell-down of Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena and is keen to find a buyer, as this would accelerate the exit. Some of the small to mid-sized Italian banks could also be targets. The chart below shows Banco BPM preferred senior spreads trading close to those of the National champions (Intesa Sanpaolo and Unicredit), suggesting the bond market views it as a potential takeover target.

ISPIM = Intesa, UCGIM = Unicredit, BAMIIM = Banco BPM, BPEIM = BPER Banca, ICCREA = Iccrea Banca. Source: M&G, Bloomberg, July 2024

Germany

Germany is among the least consolidated banking systems in Europe. However, further consolidation is complicated by Germany’s “3 Pillar” banking system, where two of the “Pillars” (the savings banks and cooperative sector) are non-profit maximising organisations, making up approximately 60% of the market. Consolidation across the 3 pillars is difficult due to the differing ownership structures and political, legal and regulatory factors. Privately-owned and listed German banks (like Deutsche Bank and Commerzbank) only make up approximately 30% of the market and consolidation within this segment is possible. Deutsche Bank has previously looked at acquiring Commerzbank and another attempt in the future cannot be ruled out. Unicredit has also been rumoured to be interested in Commerzbank, where it could merge it with its German subsidiary, HVB. Unlike in Italy, we do not think the credit spreads of German banks are currently pricing in any consolidation.

Other EU countries

The banking systems of Portugal and the Netherlands, which are already quite concentrated, may become a little more so, as they have banks for sale. Novo Banco in Portugal and De Volksbank in the Netherlands could be bought, though their respective owners may choose an initial public offering (IPO) exit rather than M&A.

In Spain, which has already undergone several waves of consolidation, the government has expressed some discomfort with the combination of BBVA and Sabadell although they have yet to officially block that merger. That said, further consolidation of smaller subscale players in Spain should not be ruled out.

European Cross-Border M&A: is it a pipe dream?

The European Central Bank (ECB) has often cited the benefits of cross-border M&A within the EU. In a speech last year, the former Head of ECB-SSM, Andrea Enria, highlighted three benefits:

- Private risk sharing – where cross-border banks are able to better absorb losses compared to local banks.

- Smoother resolution of failing banks in an integrated European market, as a failing bank’s assets/liabilities could more easily be transferred to a larger set of potential bidders.

- Lower correlation of risks between the home sovereign and the bank.

While those benefits can be significant, we do not expect to see much cross-border M&A in the EU anytime soon. Enria himself acknowledges some of the challenges, including the difficulties in extracting synergies when banks must maintain foreign operations out of subsidiaries rather than branches. With subsidiaries, local regulators usually have their own liquidity and capital requirements, which can limit the benefits of scale to the parent organisation. Other factors include legal differences (e.g. consumer rights, insolvency rules), negligible opportunity to consolidate branches (little overlap), and cultural/language differences.

European regulators are trying to harmonise some rules, such as those around “depositor preference” (the position of depositors in the creditor hierarchy in resolution). However, we think cross-border M&A is more likely to remain confined to banking groups acquiring operations in countries in which they already have a presence, such as bolt-on, asset-light, fee-income-generating acquisitions, or partnerships such as in wealth management or fully digital initiatives with a small scale. Examples of the former include Credit Agricole’s expansion in Italy or more recently the Belgian bank, KBC, which merged its Bulgarian bank UBB with RBI (Bulgaria) in 2022, growing its local market share from 14% to 19%.

US: Regulation change could encourage more consolidation, but the outcome of the Capital One and Discover regulatory approval process will be important

The US has over 4,000 banks so we will very likely see more consolidation, especially among the smaller institutions. The situation with larger banks is different, however. There are many regulatory hurdles for the so-called “G-SIBS” (Global Systemically Important Institutions), but there has been, and will surely be, more consolidation among larger regionals. Increased regulatory scrutiny on regional banks with assets over $100 billion could encourage consolidation, as it may be more efficient for those close to the $100 billion asset threshold to leap over it rather than crawl over it. However, uncertainty around regulatory and political appetite for bank mergers is currently posing somewhat of a roadblock. Capital One has launched a takeover bid for Discover which could, if approved, open the door for other M&A in this segment. While we believe the argument for more consolidation is strong (scale, synergies, etc.), regulators’ views will have a significant impact on US bank M&A activity. For example, Toronto Dominion called off its $13.4bn takeover of First Horizon in 2023 due to uncertainty about regulatory approvals. Should such approvals for large regional M&A prove difficult, banks may opt to grow organically or by acquiring much smaller institutions instead.

To sum up, we believe a healthy level of consolidation is positive for bank bond investors. However, in Europe, despite some key policymakers favouring EU cross-border consolidation, there are still too many hurdles to achieving this meaningfully. Therefore, European bank consolidation will largely remain a “domestic affair” for the time being. Whereas in the US, the outcome of the Capital One acquisition of Discover will be key in determining how much M&A we will see in the near term.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.