Indonesia’s Path Forward: Navigating a New Political Era

Over half of the world’s population have cast or will be casting their votes to elect their country’s leaders in 2024. This includes elections in eight of the world’s most populous countries: India, the US, Indonesia, Pakistan, Brazil, Bangladesh, Russia, and Mexico. Looking specifically at Indonesia, we will explore the historical political journey of the world’s largest archipelagic state from the era of Sukarno to the current ‘Reformasi’ period, examining outgoing President Joko Widodo’s tenure and the recent 2024 presidential election. We will look at the fiscal and economic challenges the new administration under incoming President Prabowo faces, the market’s reaction, and the crucial role of infrastructure investment in Indonesia’s future. While concerns about public debt and populist policies persist, we will assess other market factors that may influence the direction of the Indonesian bond market.

From Sukarno to Reformasi

Indonesia, the largest country in Southeast Asia with a population of 280 million, had 204 million eligible voters cast their ballots on February 14 to elect its 8th President. This marks only the fifth election since Indonesia became an independent republic in 1945. The first president, Sukarno, held power for 22 years after consolidating control and becoming ‘President for Life’. However, years of economic hardship characterised by hyperinflation, and rising threats from communist ideologies, led to Sukarno being replaced by another authoritarian leader, President Suharto, who ruled from 1968 to 1998. Suharto was forced to step down in the aftermath of the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis due to severe domestic economic instability, a collapsed currency, and unrest in various regions across Indonesia. The first elections were held in 1998.

Since then, Indonesia has entered a new political era known as ‘Reformasi’, marked by significant reforms to the judiciary, legislature, and executive offices, including the removal of the ‘President for Life’ title and the limitation of presidential tenure to two 5-year terms. These reforms were instrumental in transforming Indonesia into a more democratic society, enhancing the rule of law, and promoting political stability.

The Jokowi legacy: stability and growth

Fast forward to the presidency of Joko Widodo (popularly known as Jokowi), the well-loved, outgoing president whose approval rating had remained above 60% for the most part of his 10-year tenure1. President Jokowi connected with the younger population through social media and inspired many young Indonesians with his story of rising from a humble background to becoming the country’s leader through hard-work. His administration delivered strong economic development and job growth, ensured robust government budget control, and furthered reforms to the state machinery to increase efficiency and reduce corruption. The Jokowi government is regarded as the most stable in modern Indonesian political history.

2024 presidential election and the new administration

The 2024 presidential elections concluded smoothly in February, with only one round of voting. The elected pair, President Prabowo and Vice President Gibran (Jokowi’s eldest son), are seen as a continuation of the Jokowi platform. This is evidenced by Prabowo’s commitment to continuing Jokowi’s reforms, including expanding commodities downstream processing, building infrastructure, and moving the capital to Nusantara.

A balancing act: populist policies and fiscal discipline

However, this incoming administration leans towards populist policies, which will likely increase the government fiscal deficit from 1.7% to the 3% statutory limit, pushing government debt-to-GDP from the current 40% closer to 50%2. Prabowo’s campaign policies include free lunch plans for every student, higher spending on infrastructure and ramping up defence capabilities. Prabowo has suggested that the increased deficit will likely be funded by higher tax collection from improved automated tax systems and various tax reforms, including the removal of tax incentive programs. However, the feasibility of this approach remains in question: Indonesia’s tax system is manual and cumbersome, resulting in a relatively low tax-to-GDP ratio of 12.1%, compared to the average of 19.3% in other emerging Asian countries3.

Market sentiment: navigating investor concerns

Prabowo’s proposed policies have caused consternation amongst some of Jokowi’s existing cabinet ministers, as well as global financial market participants. Since the election, Indonesian government bonds have underperformed their Asian peers. Various announcements, including the appointment of Prabowo’s nephew, Thomas Djiwandono, as second deputy finance minister, have added to investors’ concerns about a possible increase in bond supply.

Despite concerns around higher public debt levels, we believe the market reaction is overdone. Even at a 50% debt-to-GDP ratio, Indonesia’s debt level is still substantially lower than other Southeast Asian economies: 66% for Malaysia, 58% for the Philippines, and 61% for Thailand4. Indonesia is unlikely to be downgraded by rating agencies since the debt-to-GDP level remains within the range for Baa/BBB-rated sovereigns.

Deutsche Bank estimates that if the deficit-to-GDP ratio increases from low 2% to 3%, even without growth in government revenue collection, the debt-to-GDP ratio is unlikely to exceed 50%5. The government can also utilise its USD 30 billion cash balance, currently three times higher than pre-COVID levels, to fund the increase in future spending, thus reducing reliance on additional government bond issuance. The Indonesian government can therefore afford to run a higher budget deficit; however, this must crucially come with greater control to prevent the corruption that has run rampant throughout its political history.

Infrastructure investment: bridging the gap

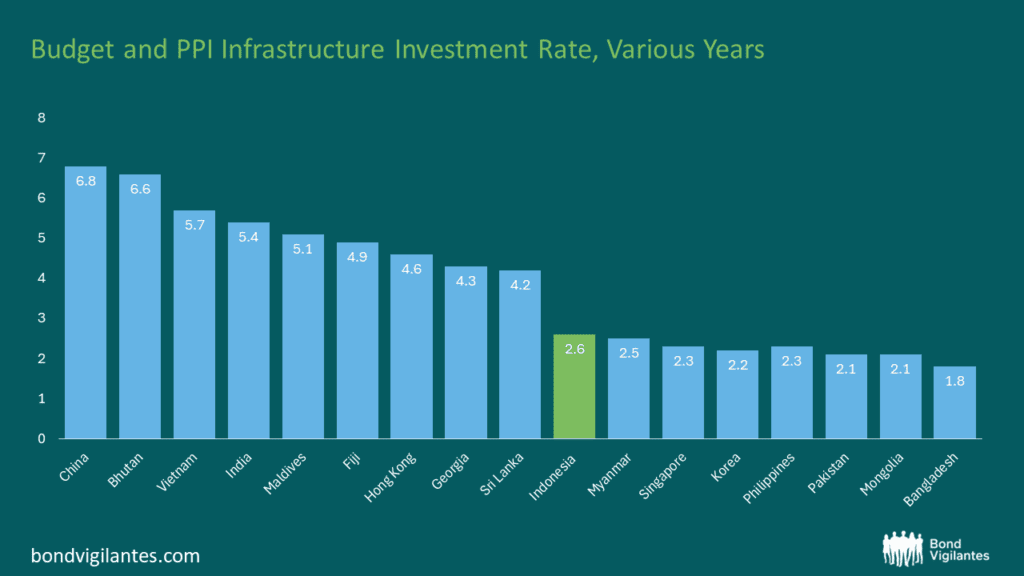

Indonesia has maintained tight control over its government budget for decades, leading to underinvestment in the infrastructure needed for the country’s growth (figure 1).

Source: https://www.adb.org/news/features/how-much-should-asia-spend-infrastructure-0, as at July 2024

While Jokowi’s infrastructure drive has helped Indonesia catch up with the rest of Southeast Asia, much work remains to improve connectivity across the nation’s seventeen thousand islands. Prabowo’s planned infrastructure push is necessary to continue diversifying away from commodity exports by enhancing infrastructure for sectors including manufacturing, processed commodities, transport, sustainable energy, and tourism. Improved infrastructure will be key to attract foreign investment and boost industrial productivity.

Future prospects

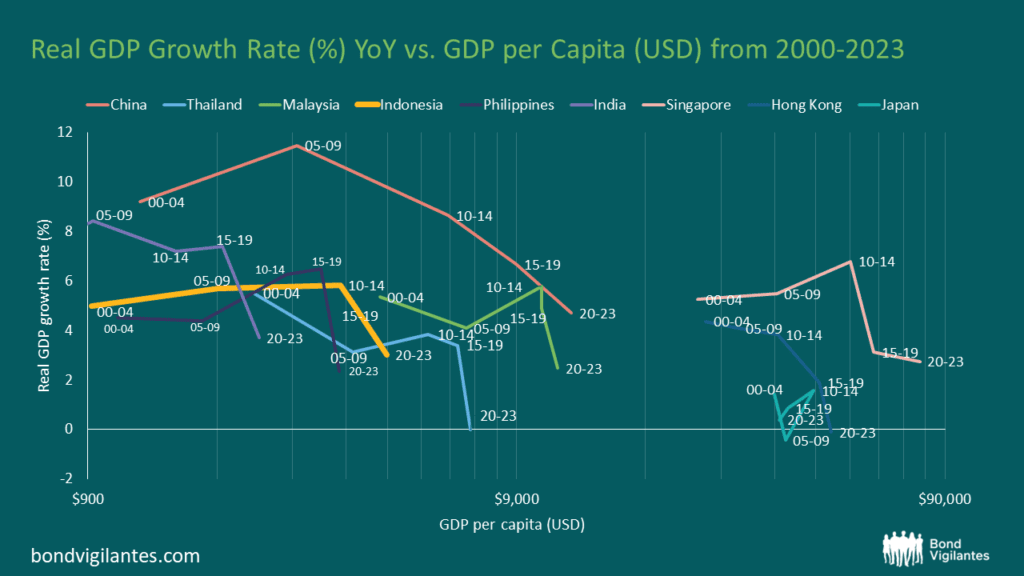

Indonesia is at a critical juncture in its economic development. With a relatively young and increasingly educated population, the country has a conducive backdrop for productivity growth. Prabowo’s GDP growth target of 8% aligns with what is needed for the country to avoid the ‘Middle Income Trap’ (figure 2) and achieve high-income status before the population starts aging.

Source: https://oecdecoscope.blog/2017/09/25/the-middle-income-plateau-trap-or-springboard/, as at July 2024

Indonesia has posted strong GDP growth of over 5% for the last three decades, except during the Asian Financial Crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the rate still undershoots its growth potential of 7-8%. Currently Indonesia is a lower-middle income economy with GDP-per-capita of USD 4,788 in 20226. Achieving high-income status will require coordinated efforts from both the public and private sectors to expand economic developments.

Investor outlook

We will continue to monitor Indonesia closely over the coming months as details of economic policies and incoming ministerial appointments are finalised. Global investors will remain cautious about any departure which is perceived to be a step away from the direction of Jokowi’s administration. Meanwhile, Bank Indonesia (BI) and US monetary policy will remain the key drivers of domestic bond market performance. BI’s ability to follow the pace of US rate cuts depends on the stability of the Indonesian rupiah. The issuance of short term notes (Bank Indonesia Rupiah Securities or SRBI) at 7.0 – 7.5% for a 12-month tenor has improved the rate of return on the rupiah. If this proves effective in stabilising the currency and with foreign investors’ participation in Indonesian government bonds at an all-time low, we believe the conditions are improving for Indonesian bonds to join a global rally led by rate cut expectations.

1 Source: M&G Investments estimates, based on various media reports, July 2024

2 Source: Deutsche Bank estimates, June 2024

3 Source: OECD, Revenue Statistics in Asia and the Pacific, 2022

4 Source: IMF, Bloomberg, 2022

5 Source: Deutsche Bank estimates, June 2024

6 Source: World Bank national accounts data, and OECD National Accounts data files, 2022

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.